As Canada and other Western nations ramp up their efforts to build stronger political and economic ties in Asia, business groups are calling on the federal government to finally lock in a trade agreement with India.

The Business Council of Canada and the Canada India Business Council released a report on Thursday that looks at Canada’s current trading relationship with India and the economic benefits that would come from establishing a trade agreement.

The report, which includes analysis from Ciuriak Consulting commissioned by the two councils, calls India “one of Canada’s largest untapped trade opportunities” and compares its economy to where China was two decades ago.

The analysis finds that while trade with India has grown on average by nearly 12 per cent over two decades, Canada has lost its market share over the years.

“The best path forward is a comprehensive economic partnership agreement (CEPA) with India,” the report says, estimating that such an agreement would increase two-way trade by $8.8 billion a year and bring about an annual GDP boost of 0.25 per cent by 2035.

Trade negotiations between Canada and India began in 2010 under the Conservative government of former prime minister Stephen Harper.

Twelve years later, a deal has yet to be struck.

After years of no movement on reaching a deal, Canada and India announced in early 2022 that they resumed talks toward a comprehensive free-trade agreement.

The announcement was made following a trip to India by International Trade Minister Mary Ng.

Ng and her Indian counterpart, minister Piyush Goyal, agreed to relaunch negotiations with an effort to secure an early progress trade agreement, which would hold in the interim until progress is made on establishing a comprehensive trade agreement.

The two ministers have been holding monthly calls since the visit to further talks.

According to a senior government official with knowledge of the negotiations, an early progress trade agreement is expected to be reached in the coming months.

The official, who spoke on condition of anonymity to share information not yet public, said the agreement will avoid contentious trade-related issues that would require more time to negotiate.

The potential for an agreement comes as the federal government works toward releasing its Indo-Pacific strategy, which will aim to further its political and economic reach in the region.

Vivek Dehejia, an associate professor of economics at Carleton University, says the term “Indo-Pacific” itself is an attempt to boost India’s prominence in the region, which was previously referred to as the “Asia-Pacific.” That shift, he says, is driven by the West’s perception of China as a threat.

When it comes to Canada’s interest in a trade agreement, Dehejia says India being the fastest growing major economy makes it an attractive country from a trade perspective.

However, the economist, who researches globalization and economic development of India, says trade between the two countries is relatively small compared to other countries. In 2021, India was Canada’s thirteenth largest trading partner.

“The elephant in the room is that the real driver of the relationship between Canada and India, I don’t see anymore as the economy, it really is diaspora-driven,” Dehejia said.

The Indian diaspora, which is concentrated in metropolitan regions like the Greater Toronto Area, is made up of swing voters, he said, adding a political incentive to reaching a deal.

In terms of Canada’s prospects in securing a deal, Dehejia said there are some positive signs that such a deal may indeed be on the horizon. While India has historically been closed off to trade negotiations, it has recently shown more openness to such negotiations.

India and the United Kingdom are expected to reach a free-trade agreement this fall and India has also revived trade talks with the EU.

“I think (India) realized that trade is just too important for them to put that on the back burner,” he said.

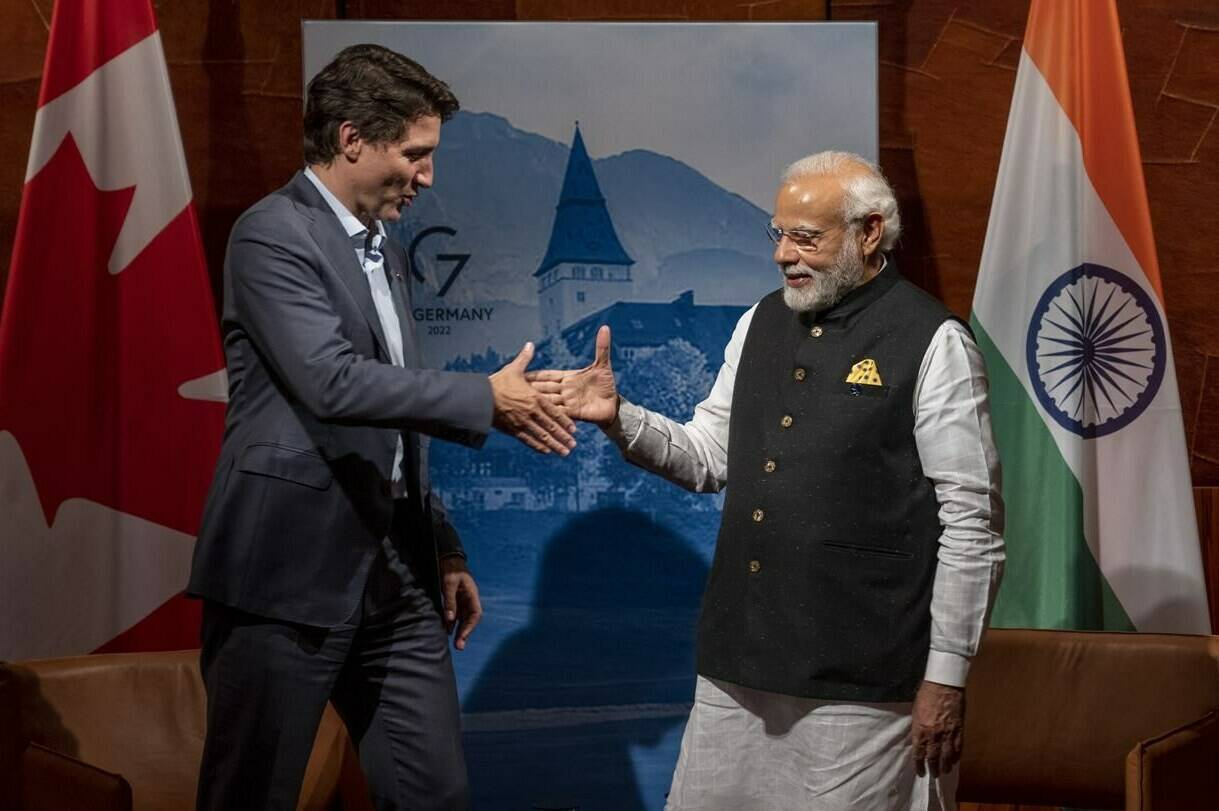

Dehejia said there is also the incentive for Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to secure a deal and post it as a win for his government.

In February 2018, Trudeau paid a visit to India, where official business was overshadowed by his family wearing traditional Indian clothing and the invitation of Jaspal Atwal, a convicted attempted murderer, to two official events.

India’s pursuit of trade deals comes as many countries, Canada included, are taking stock of their position with China amid growing concerns about human rights.

Like China’s leader, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has also been widely criticized for perpetuating human rights abuses, including in a Human Rights Watch report last year that accused his government of subjecting its critics to surveillance, politically motivated prosecutions, harassment, online trolling, tax raids and the shutting down of activist groups.

India has also refused to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine due to long-standing diplomatic ties with Moscow and reliance on Russian weapons.

Dehejia cautioned that for negotiations to be successful, however, it would be best to avoid mixing social policy with trade policy, noting that Canada’s criticism of the Indian government has been poorly received in the past.

In 2020, Trudeau made remarks in support of protesting Indian farmers, saying he was concerned about the protests in India and that Canada would always support the right of farmers to be heard. In response, the Indian government had said those comments amounted to interference in its affairs and potentially damaging to its relations with Canada.

“In some ways both governments have to try and sort of compartmentalize the trade agreement and use that to say, look, you know, Canada-India relations are finally improving. We finally got this trade agreement,” said Dehejia.

Nojoud Al Mallees, The Canadian Press