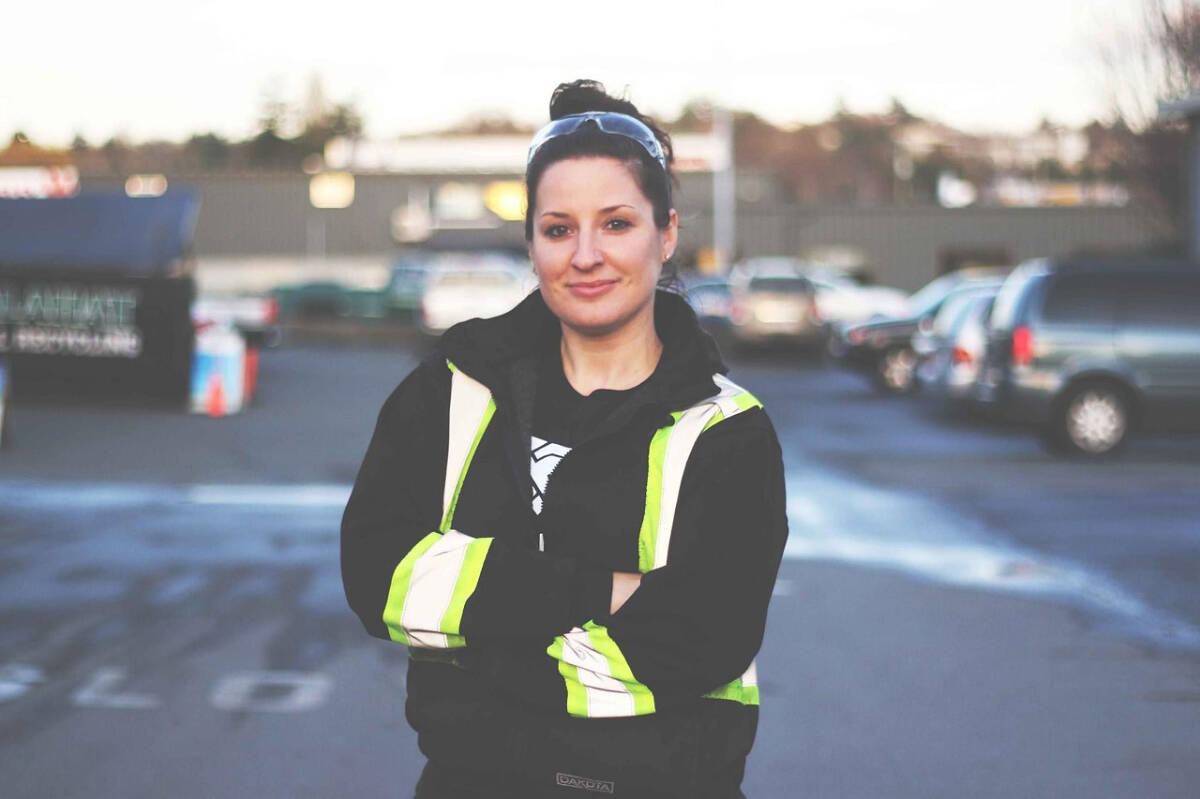

After years of working several unfulfilling desk jobs, B.C.’s Liz Barrett wanted a change.

She looked around and came across the Workplace Alternative Trades Training or “WATT” Program, a program run by the Western Joint Electrical Training Society and designed to get people through the initial barriers of learning a trade.

Getting into the course is competitive, but if you do, those enrolled can complete their initial safety courses for free and then be set up with the electrician union and job placement.

Within weeks, Barrett had found a placement with a Victoria electrician and was loving her position. She was a hard worker, biking to worksites with her tools in one backpack, and her lunch and a change of clothes in another.

The position was part of her electrician apprenticeship – which usually lasts four years and is split between work periods and studying for school.

Then after around a year, Barrett got pregnant with twins, meaning she had to go on maternity leave earlier than she would have wanted. After giving birth, Barrett planned to stay on maternity leave for a year and then return where she left off with her apprenticeship.

But 21 months after her twins were born, and 27 months after she went on maternity leave, Barrett still hasn’t been able to return to work because she can’t find any child care.

She’s been trying for months to find a space, but the race for child-care spots in Greater Victoria is competitive. The opportunities are even tighter because of the nature of trades work, where Barrett would often have to be on-site for 7 a.m., which rules out a lot of daycare centres that open later.

“I haven’t ever talked to like an employer about, ‘Hey, can I start later?’ because I don’t want to be that person that gets quote unquote, special treatment, even though it’s not, it’s just the only way you can make something work because of the situation. It’s brutal out there. I phone all the time. And I’m like, ‘Is there any movement? Is there any movement?’ And nobody really seems to have any.”

That slow culture change is another problem that’s plaguing an industry that is “tortuously inflexible,” according to Nick Black, a carpenter and owner of Cavetto Carpentry.

Black’s company is a small, four-man team and has been looking to expand but is struggling to find a “unicorn,” his term for a trained apprentice who’s ready and available to work.

“The trades have notorious negative sides to it, that are kind of stigmatized right now. I think a lot of people have this standard view of the trades, which isn’t great. But I think the trades are also very, very slow to change and it just can’t afford to do that anymore. The whole industry needs to really modernize and update because we’re not just competing with each other for labour, we’re competing with every other industry that has made those changes.”

Black says a number of problems plague the trades, including kids being turned off them by parents and schools when they’re young, and companies who take on apprentices but use them for cheap labour instead of proper learning opportunities. Added to that are the child-care issue, pay, as well as a lack of affordable housing crisis, parking at worksites and a lack of benefits.

“I think on one end, our hand and the industry’s hand is being forced because just otherwise people just aren’t going to do it,” he said. “We have to bend over backward for our people. But also, I think that’s the right way it should be.”

Black said he’s been looking for a benefits package for his team, but it’s hard to manage the overhead with such a small team.

On child care, Black suggested small contractor companies should band together and establish a child-care facility for their members, one that would offer cheap spots that work with the typical schedule of a tradesperson. That would be an innovative solution but a complicated one to get running, admitted Black.

In the meantime, the shortage of workers is only set to increase.

A Royal Bank of Canada report released in September 2021 forecasted that 700,000 tradespeople out of the four million working in Canada would retire by 2028. That combined with flawed recruitment means Canada will face a shortage of at least 10,000 workers in every nationally recognized Red Seal – a national trades certification – trade by 2026.

That’s hurting businesses.

A survey conducted by Canadian Manufactures and Exporters of over 500 manufacturers found that over the past year (the report came out in October 2022), 62 per cent of manufacturers had lost or turned down contracts and faced delays due to a lack of workers, leading to $7.2 billion in lost sales and penalties for late delivery. Meanwhile, 43 per cent of companies had postponed or cancelled capital projects because of labour shortages, leading to $5.4 billion in lost investment.

But it also means people like Barrett are being held back or in other cases left out entirely.

“I finished one of my years of schooling when I was around 32 weeks pregnant. So I’m ready to go back to work and build up my hours.”

At the beginning of 2022, the federal government announced nearly $1 billion annually in apprenticeship supports through grants, loans, tax credits. But Black says there needs to be a societal shift if the shortage of tradespeople is going to be properly addressed.

“There needs to be that shift in mentality in the public as well, that the trades are needed and something to be respected, not like, ‘Oh, you’re, a lower class of person.’ Well, you hired us to help you and that’s what we’re here to do. You need us, the world needs trades. They need craftsmen that can do this stuff, and do it well.”

ALSO READ: Nunavut reaches $10-a-day average for child care, years ahead of Canada-wide goal

@moreton_bailey

bailey.moreton@goldstreamgazette.com

Like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.