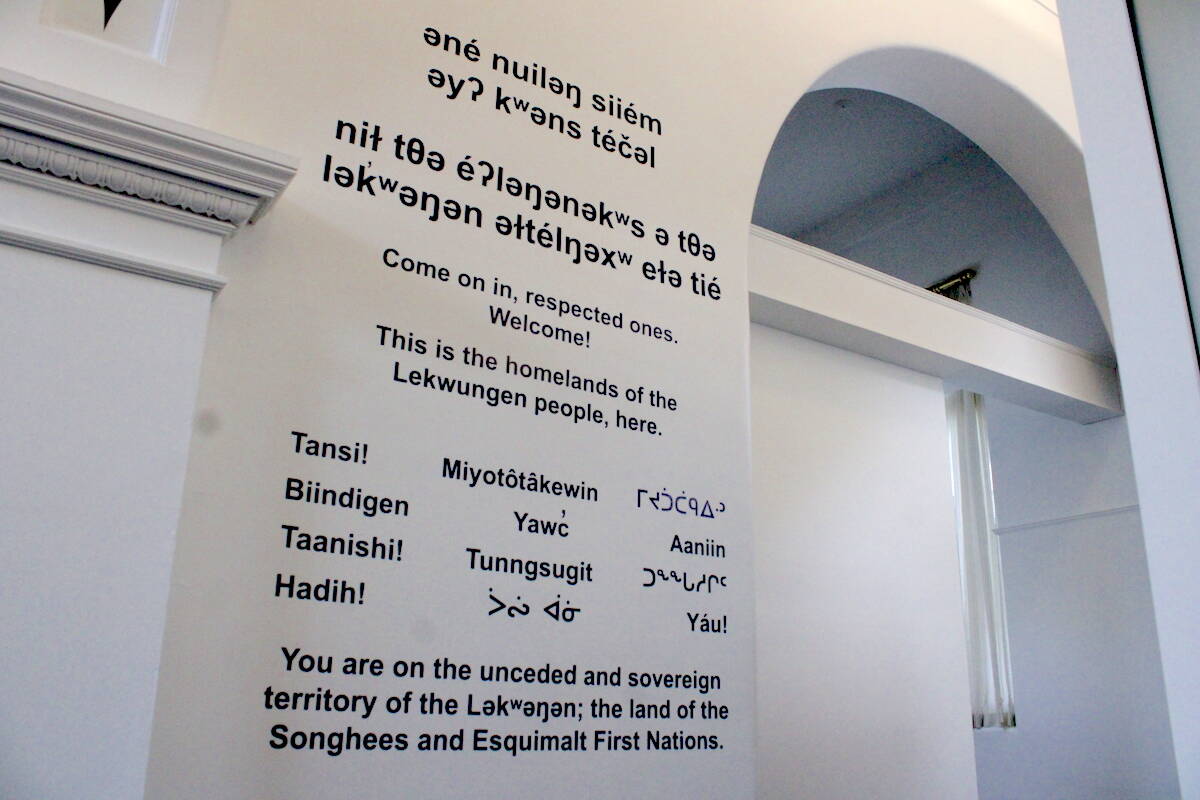

Inside the former Carnegie Library building in Victoria, Indigenous artwork of aquatic plants clings to the colonial structure’s barrel-vault entrance. The art extends throughout the building, showing sprigs of cedar or swirling salmon infused into panes of glass that make up office walls.

The imagery is meant to offer a sense of comfort to those walking through what’s now the Victoria Indigenous Justice Centre.

“How are we going to make this so that it doesn’t seem so colonial and doesn’t have that extremely daunting feeling when you walk in,” a representative for the centre said as she gave a tour of the building on Tuesday (April 30). “If we can de-colonize some of the look and the feel of the space, then we can reclaim this area and make sure that people feel safe in it.”

The centre offers culturally grounded, trauma-informed legal support and other outreach services for First Nation, Metis or Inuit people having to navigate criminal or child and family court matters. Despite having a wide-ranging mandate, the centre aims do two main things: reform a legal system designed to harm, control and hold back B.C.’s Indigenous people, and restore Indigenous legal orders and traditions.

While alleviating fears around navigating the justice system, the agency is also providing legal services to individuals who otherwise would’ve gone to court with no lawyer to represent them.

The Victoria site is one of five new justice centres that opened this winter, bringing the provincial total to nine as six more are set to open in rural areas by 2025. The roll out of the centres is one of 25 strategies within a justice plan for Indigenous people that was created in 2020 by the provincial government and the BC First Nation Justice Council.

The Victoria centre takes a holistic view as it recognizes several challenges may be contributing to why an individual had to walk through its doors. Aside from it’s eight staff lawyers, the site also includes outreach workers who can connect clients to mental health, addictions treatment or housing supports.

It aims to avoid the status quo of Indigenous clients being left to go to law firms where they could get overwhelmed with dense amounts of legalese being thrown at them in a short period. The Victoria site instead looks to pair clients with a staff member right as they walk in, before offering cultural programming or sharing a coffee or tea.

“That’s in a very Indigenous way where we don’t go just straight into business and leave you out in a cold waiting room, we want to make sure you feel cared for,” said Michael Jakeman, a lawyer who oversees the Victoria, Surrey and virtual Indigenous Justice Centres.

Reducing negative criminal justice outcomes that disproportionately affect Indigenous people is key to the justice centres’ mission.

Despite only being five per cent of Canada’s population, Indigenous Peoples accounted for 32 per cent of individuals in federal custody, according to most recent data. That proportion has been rising over the last decade and Indigenous individuals made up half of all federally incarcerated women in 2022. In B.C., under one in 10 children are Indigenous, but that group makes up almost 70 per cent of those in provincial care.

Jakeman explained how individuals can quickly get consumed by the justice system. If a person is accused of a petty crime but lacks the resources to track their court dates, they may miss those appearances and face additional legal trouble.

“While you might of had a defense to the original charge, now you are guilty of breaching the court order,” the clinial legal supervisor said at the Victoria centre. “Once you get in the court process, the promises you make to the court are now the heaviest in gravity, and those can continue and are harder to defend.”

It can also be difficult to secure a bail plan for Indigenous folks, especially those without a home or individuals who lack family and other support systems, Jakeman said. The federal government says Indigenous Peoples continue to be denied bail more frequently than other groups accused of a crimes.

The justice centre’s wide scope of services also include a police accountability oversight unit, women’s and youth teams and in-house Indigenous elders who can offer guidance and knowledge to clients.

The centre’s representative said B.C. is leading the charge on Indigenous justice reform in Canada, with other provinces and the federal government being informed by what’s being done on the West Coast.

READ: Esquimalt low-income residents fighting against eviction notice