Yves Côté is a hardworking, compassionate, affable 60-year-old man.

If you meet the Chilliwack resident you won’t see the terrible experiences he has endured, nor the terrible things he has done.

The second youngest of eight children, Yves’ mother died when he was young, propelling him into the foster care system where he suffered serious abuse for his entire childhood.

Between the ages of five and 17, he lived in numerous foster homes, juvenile detention facilities, and more than one psychiatric hospital, all in Quebec.

As Yves emerged from an unenviable childhood, soon after he turned 20 he did the unthinkable. His older brother Beavis had treated him horribly, physically and mentally tormenting him for years.

“He was a bully and he was extremely cruel,” Yves said in an interview with The Progress.

With the help of three of his brothers, Yves convinced Beavis to meet them at their father’s house. There, the four of them kept Beavis hostage for three days, beating him repeatedly, torturing and threatening to kill him.

“On the third day, I grabbed his head, tilted it back, put his own gun under his chin, and shot him.”

So began 40 years of a violent criminal adulthood mostly spent in maximum security prisons in Quebec.

How could a person who spent 32 years incarcerated recover and become a contributing member of society?

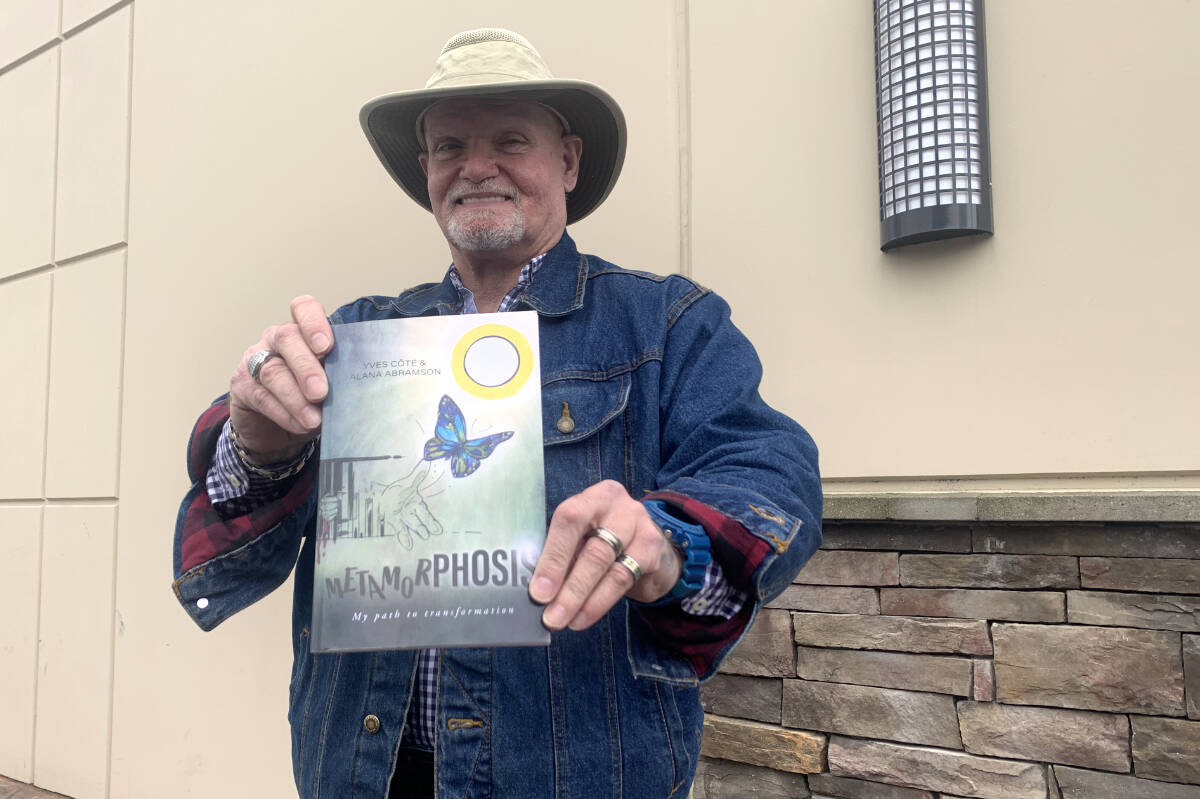

That’s what Yves outlines in the book co-written with criminologist Alana Abramson, titled Metamorphosis: My path to transformation.

Beavis didn’t die the day Yves shot him, and Yves received a 42-month sentence for attempted murder and other crimes.

From that sentence in January 1982 until his release on day parole on Dec. 6, 2013, a little under 32 years, Yves was only out of prison for 11 months.

“My sentence is not the years that I got,” he says. “My sentence is having to live with what I’ve done for the rest of my life.”

A lifetime behind bars

Going to prison meant learning how to survive. Violence is omnipresent in maximum security institutions such as Donacona in Quebec City where Yves spent many years.

But for Yves, it wasn’t unfamiliar coming from an abusive household. He did OK in prison, becoming the type of person inmates fear because being feared was a way to survive.

“Fast forward 10 to 15 years: I am in prison serving two life sentences, one for first-degree murder and one for second-degree murder,” he writes. “I’m five-foot-seven inches and 225 pounds and my body is covered with tattoos. I have been working out for 20 years and was known as one of the strongest men in most of the institutions I have served time in. I have used violence while in prison as an instrument to get what I want. I became like the men that I feared when I first entered prison.”

Meeting Yves at The Progress office, sitting down with him for an interview, this patient, respectful, self-aware man is incongruous to the violent killer he explains that he was in the past.

What is interesting about Metamorphosis is to see that, however rare it might be, humans can change and according to Yves, they change in spite of Canada’s corrections system, not because of it.

Ask him about capital punishment and for a man who has committed the most serious offences in the criminal code, his answer is surprising.

“I would have chosen capital punishment if I could have,” he says.

The maximum sentence in Canada of life in prison with no chance of parole for 25 years is a waste of a life for Yves.

He believes the worst should be life with parole consideration after 10 years because at least that gives an offender a light at the end of a tunnel.

Inmates serving life lose all hope so they become hardened, committed to the prison life, the very opposite of rehabilitation so touted by Canada’s system.

“A life-25 sentence is very hard to imagine when you are young,” he says. “Where’s the hope? Hope is a terrible thing to lose.”

If a man is given 10 years to change then that’s a positive outcome for the system. And if he can’t change? He stays incarcerated.

“If you have a couple of decades to do in prison, that’s a long (expletive) time,” he says. “In the time I spent in there, they could have made a brain surgeon out of me.”

Despite being someone who is now out of prison, with a second – if very late – chance in life, he doesn’t blame his upbringing for the crimes he committed and it drives him crazy to see other offenders do the same.

“A lot of the guys (in the prison system) have been abused when they were kids, a lot of the guys got sexually abused, too,” he says. “I remember sitting in restorative justice circles and hearing sexual predators complaining because they are saying ‘I got sexually abused so that’s why I’m a pedophile.’ I say, ‘Wait a minute, I was sexually abused when I was a child and it’s the last thing I would want to do to someone else. You are a sex predator because you are a (expletive) creep.’”

He applies the same principle to bullies.

“I ask the guy who says he was bullied, ‘Well why do you want to do it to other people?’”

“Blaming others is always easier than taking responsibility for your own actions,” he writes in the book. “No one forced me to kill anyone, to pull the trigger six times, to stab a man many times.”

Yves’ book is eye opening for the lay person who knows nothing about lives of violence, abuse, and conditions inside the harshest of federal prisons.

It also sheds a light on what some say is impossible, or at least very rare, namely that criminal offenders can serve time and go on to live productive lives.

“My purpose to the book is to show there is a reason why we become who we are but also, we can change.”

Metamorphosis: My path to transformation is a self-published book available through the author who can be contacted at 604-997-4265 or email chefrealyves@gmail.com

RELATED: B.C. writer, former undercover officer, pens novel based on experiences

Do you have something to add to this story, or something else we should report on? Email:

editor@theprogress.com

Like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.