Concertgoers are rushing back to shows and more musicians are on the road than venues can schedule. At first glance, it might seem like the live music scene is booming for everyone.

“That’s not the case,” says music manager Sheri Jones. “It’s much harder to sell tickets.”

With almost three years of postponed shows backed up and many musicians promoting pandemic-era albums, Jones says the market is flooded with “a ton of options” for ticket buyer.

But industry players say the world’s biggest touring names are cannibalizing ticket sales for everyone else, particularly artists without the promotional heft of a major label and sponsorship deals.

Jones recalls a recent hometown show for Halifax folk singer Willie Stratton that teetered on that uncertainty as it was booked for around the same time powerful legacy acts rolled into town.

“I was flipping out about ticket sales because James Taylor was here one night, and three nights later it was ZZ Top,” she says.

“Two days later Willie Stratton was playing. Who are you going to spend your money on? You’re going to go see the artists you might never see again.”

Stratton ended up drawing a satisfying crowd, she says, but similar anxieties are rampant with managers across the country.

Soaring inflation has put the squeeze on finances, while there’s a looming threat that COVID-19 illness among the crew could lead to show cancellations. Without album sales to fall back on, some say the financial stakes of mounting a tour are high.

That’s left managers tossing out the pre-pandemic playbook while some musicians wonder whether touring is even worth the mental and physical toll.

“It’s kind of a Wild West,” said Sarah Fenton of Watchdog Management, which represents Mother Mother and Peach Pit.

“I wouldn’t even hazard a guess as to when things will go ‘back to normal.’ I don’t know if they will.”

Liam Killeen, who manages the Tea Party and Classified at Coalition Music, said he’s coming down from a shot of adrenalin delivered over the summer. Audiences flooded back to shows, many of them outdoors, making it seem as if the concert industry was quickly getting back on its feet.

“We had the incredible Roaring ‘20s feeling we were all promised,” he says. “And now the reality of where we (truly) are at has crept in.”

Adding to the precariousness is the rising cost of necessities, which leaves less money for entertainment, he said.

“Each fan has a finite amount of money and when they go out to buy groceries it’s $20 or $30 more,” he says.

“Does that take two or three concerts they would normally go to out of the equation?”

He says some touring acts who were reliable draws a few years ago now have trouble selling tickets. It’s left management and record labels wondering if that’s a temporary COVID hiccup or a permanent shift in who’s coming to shows.

“It’s going to take the next six to eight months to see how healthy we really are as a year-round touring business,” he added.

“We’re going to see a lot of artists that don’t have to go out maybe take a back seat for a minute and see things play out.”

Some musicians have already concluded that’s the soundest business decision.

International acts Santigold, Animal Collective and Little Simz are among the performers who’ve cancelled tours, saying the business model — which often leaves the artist bearing the financial risk — is fundamentally broken.

Edmonton-raised Cadence Weapon predicted on Twitter that “small to mid-sized ‘get in the van’ music tours will become a thing of the past” because margins are too thin, while Montreal singer-songwriter Tess Roby said she can’t see herself touring in the foreseeable future.

Alternative rock band And You Will Know Us By the Trail of Dead took a different route when they launched a US$12,000 crowdfunding campaign in September because they were “struggling with current touring costs.” They passed the goal by $3,000.

Loreena McKennitt factored in pandemic uncertainties and financial risk when she planned a small Ontario tour in December to promote her holiday album. The band and crew will return to their homes around Stratford, Ont. nearly every night, a move that will save on soaring hotel costs.

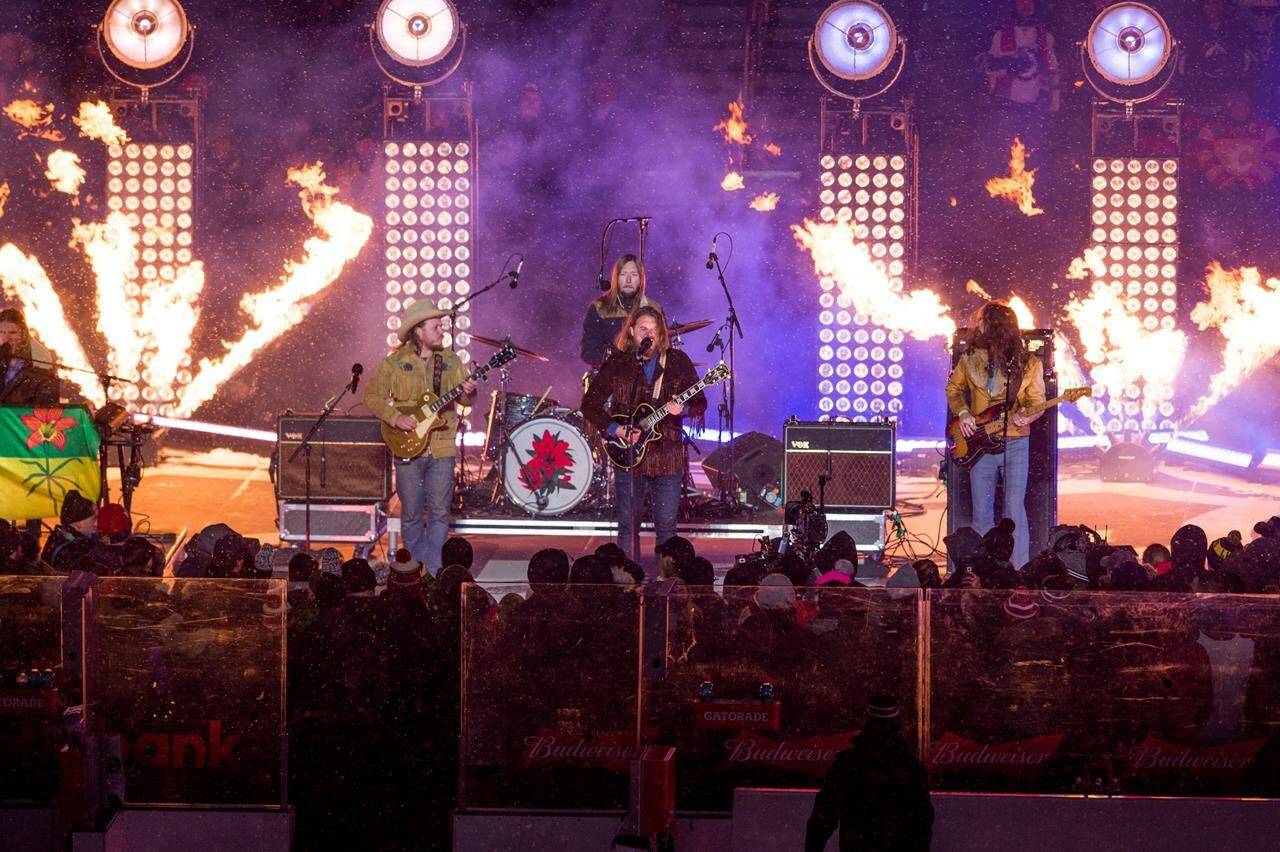

Ryan Gullen, bassist in the Sheepdogs, says the Saskatoon-founded rock band considered their mental health when they mapped out dates for their latest tour. The band will play shorter legs with breaks of nearly two weeks between each run.

He says after the pandemic forced them to stop touring, the Sheepdogs found they weren’t ready to spend “months on end” travelling on a bus.

“We wanted to ease back into things, keep everybody’s spirits high and everyone feeling good,” he said.

“You have to be smarter about how you do things at this point.”

Some musicians have found the unpredictability of modern road life comes with a whirlwind of emotions.

East Coast folk singer-songwriter David Myles learned that in early October as he prepared for a multi-province run of dates that he assumed would be his last. He worried tightening profit margins would make the prospects of mounting another tour impossible.

But a month later, he says his attitude toward touring has changed. Sales at his merchandise table have helped erase the “doom and gloom” he was feeling a few weeks earlier.

“I thought it was going to be super hard, but it’s felt great,” he wrote by text while on the road.

“It’s been a positive experience and reassuring in many ways, strangely.”

—David Friend, The Canadian Press

RELATED: Elton John pays tribute to Queen at his final Toronto show: ‘She worked bloody hard’

RELATED: Taylor Swift announces 27-date US stadium tour in 2023