Horror film scholar Dr. Kelly Doyle has some opinions about scary movies and, in time for Halloween, some suggestions about the best ones to watch.

At KPU Surrey, Doyle teaches English and other courses including Horror Writing in Popular Culture and The Evolution of the Zombie in Horror Film.

Horror is Doyle’s research interest and also hobby, as a judge at Vancouver Horror Show Film Festival, among other interests.

“I’ve loved horror film and literature since I was a child,” says the Newfoundland-raised prof, “but I didn’t realize it could become a serious area of academic enquiry until I did a theory course on identity politics and happened to see ‘28 Days Later’ around the same time. It clicked that horror has always been entrenched in very serious questions around culture, politics and identity.

Scary films offer emotional catharsis and escapism, she says. And no matter how bad things are, they are worse in scary movies.

Doyle explains.

“Thematically, scary stories can also teach us resilience in the face of darkness, pose answers to the question of what, if anything, waits after death, and best of all, many scary movies are scathingly critical of societal norms and values and are effective at doing it because so many people historically think they have nothing to offer. Beneath the blood and gore and camp and scares are often very politically and socially astute commentary.”

Below are Doyle’s picks for the top five scary movies, and why.

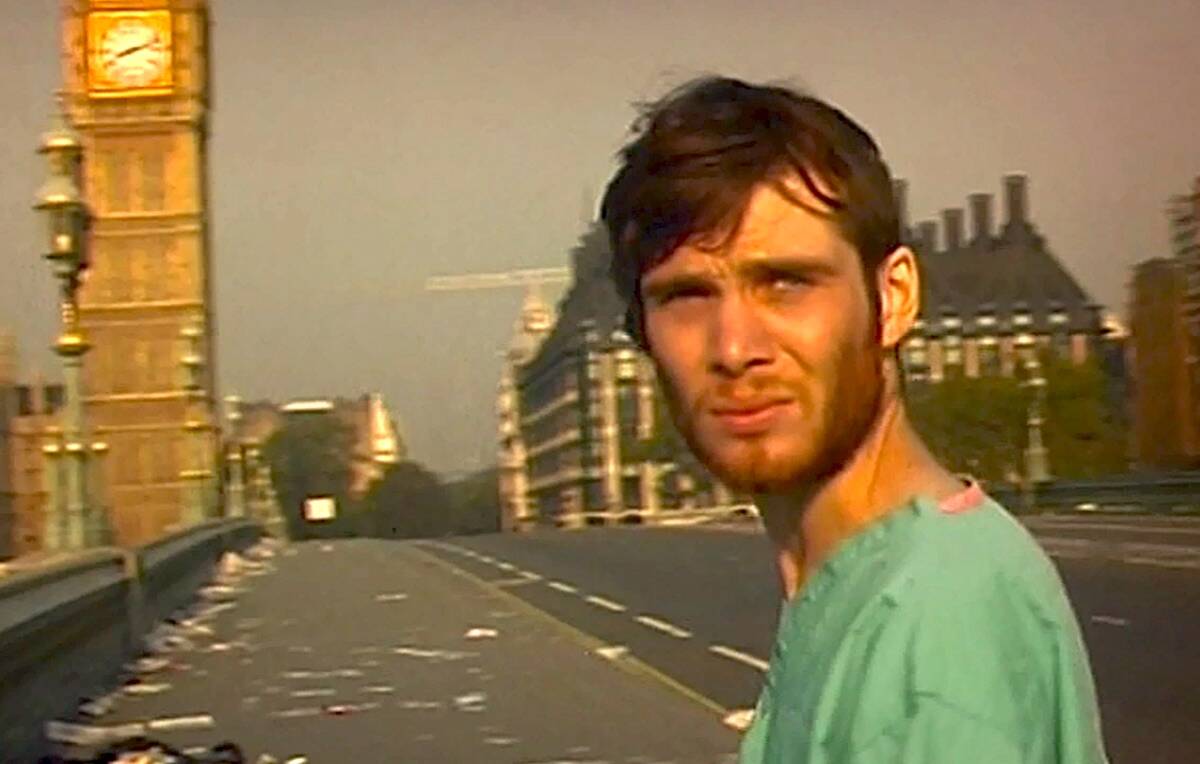

28 Days Later (released in 2002): “Think zombie films are stupid? Unrealistic? So did I, until this one not only made me aware how zombie films are, and always were, scathing commentaries on sociopolitical issues that remain germane to our time. The soundtrack is haunting, relentless, and incredible against an empty London infested with the infected. This one paved the way for the ‘fast’ zombie, and yes, these are zombies. This is also the film that helped me dream my PhD thesis into existence and remains my all-time favourite.”

Midsommar (2019): “This one will make you uncomfortable and you won’t always be able to put your finger on why. Such is the talent of Ari Aster, who situates us in the bright, pastoral, and beautiful Swedish countryside, where every slight transgression against social norms around sexuality, consent, death, and trauma are in plain view. It’s the juxtaposition of the beautiful with the profane that makes this one powerful, but more so, the way the film takes us on Dani’s journey through trauma and invites us to live in it with her.”

The Descent (2005): “Refreshing because it’s a horror film all about women that manages not to sexualize them even once. There’s a male extra or two and all of five minutes with the husband of one of the main characters, and then we follow six complex and nuanced women who are educated, funny, complicated, brave, and badass into a caving expedition gone wrong. This one will take your breath away if you are already claustrophobic long before these women end up having to fight a totally unexpected adversary.”

Let the Right One In (2008): “A truly unique take on the vampire, the story follows 12-year-old Oskar, a boy who is relentlessly bullied to the point of assault and deeply unhappy, until he meets the new girl named Eli and starts to give him the will to fight back. Spoiler: Eli is a child vampire. The film explores the isolation, dashed dreams, and darkness in the lives of the adults in Oskar’s periphery as well as his own deep desire for a real friend while inviting us to question what is monstrous in everyday society.”

REC (2008): “The viewer follows reporter Angela Vidal and her cameraman into a local fire station during the night-shift and accompanies them to an apartment building. When they are quarantined there with the residents – and something else – the film begins to unravel a mystery of contagion and possession. Like all the best horror films, this one amps up the mystery, the tension, and some unsettling scares by forcing us to go places we really don’t want to. It also comments on attitudes in the country towards immigrants and questions our fascination with reality TV.”