The plan to enable Canada to reach its 2030 targets for greenhouse-gas emissions doesn’t quite measure up, the federal environment commissioner says in a new audit.

Jerry DeMarco did a deep dive into the government’s emissions reduction plan as part of a series of fall audits tabled Tuesday in the House of Commons.

The plan, published last year, is a requirement under the federal net-zero accountability law passed in 2021. It is supposed to lay out a road map for Canada to hit its emissions targets, including the next big one in 2030.

It’s “better than previous plans” but is still lacking in a number of ways, DeMarco said: Key policies have been delayed, it’s not clear how those that have been established will work and Canada remains several million tonnes short of its goal.

“The need to reverse the trend on Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions has grown only more pressing,” said DeMarco. “This is not my first time sounding the alarm, and I will continue to do so until Canada turns the tide.”

Canada’s 2030 target would require emissions levels that are 40 to 45 per cent lower than they were in 2005. That would require current emissions to be reduced by about one-third before the end of the decade.

The measures in the plan will only reduce current levels by about one-quarter by then, DeMarco said — and that’s using government modelling that lacks transparency and is based on what he called “overly optimistic assumptions.”

Those include a rosy view of how quickly some of the major policy pieces would be implemented, and fail to account for the impact of climate change in the meantime.

For example, the government’s modelling assumed there would be no new natural gas electricity plants without carbon-capture technology after 2023, because clean electricity regulations barring them would be in place.

But to date, those regulations have only been published in draft form, DeMarco said.

More than 80 policies and programs are listed in the plan, but fewer than half of them have a timetable for implementation, and only four have a specific target for cutting emissions, he added.

And even as some sectors are successfully cutting emissions, such as electricity production from the closure of coal-fired power plants, that progress is being swamped by increased emissions from higher oil and gas production, as well as transportation.

Overall emissions are about 14 per cent higher in 2021 than they were in 1990, but emissions from oil and gas production are up 89 per cent in that time frame.

“If they don’t get a handle on the total amount, there’s no way of meeting their target, which is a total amount,” he said. “It’s not just about getting more efficient at polluting, it’s about actually reducing the amount of greenhouse gas is being emitted.”

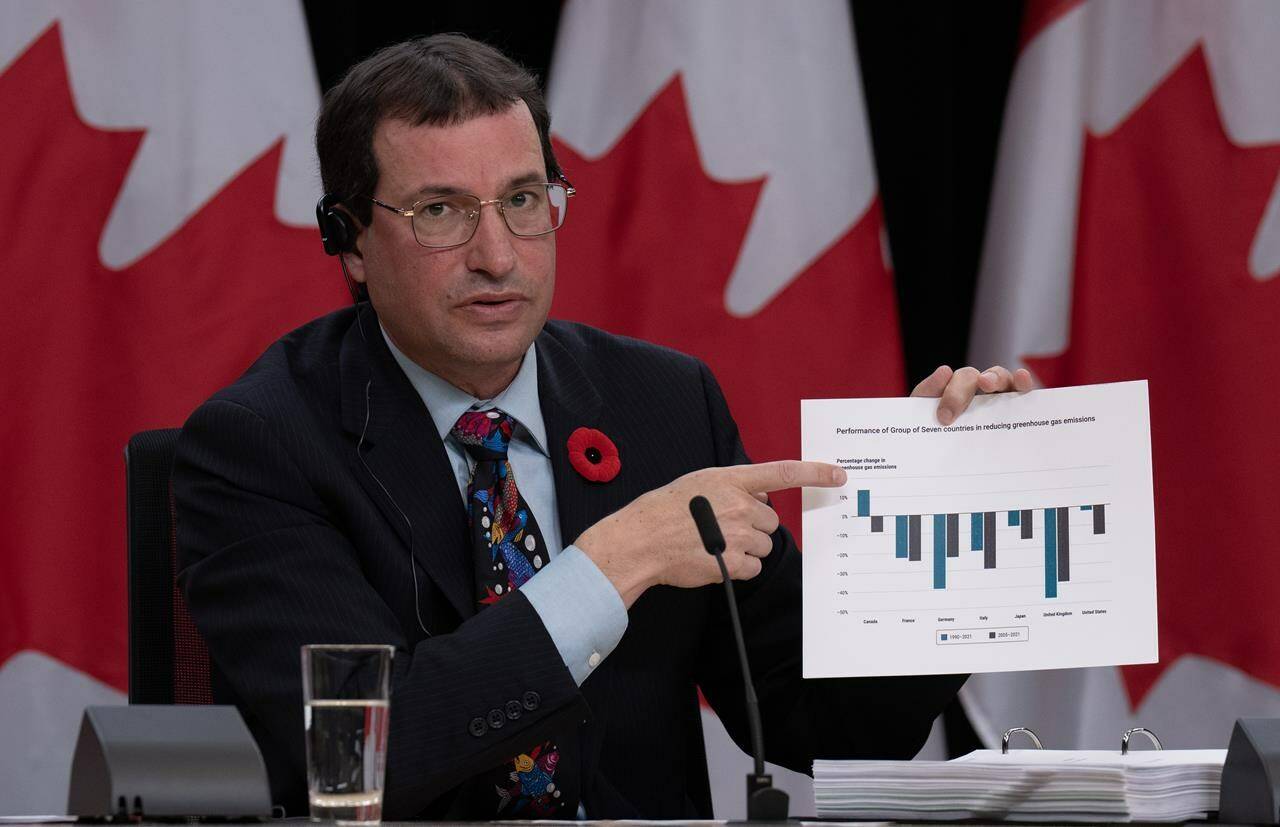

While all G7 countries, including Canada, have shown a decline in emissions since 2005, which is the baseline year for the 2030 target, Canada remains the worst performer on the list.

Emissions in Canada are down about eight per cent compared to 2005, while the reduction in the United Kingdom is about 40 per cent, 30 per cent in Italy, more than 20 per cent in both France and Germany, and about 15 per cent in both Japan and the United States.

Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault said he knows there is still a gap between the target and the policies necessary to get there.

“I agree with the commissioner, we need to do more,” he said. “We need to do it faster and that’s exactly what our government is doing.”

Guilbeault said the government is working on updating and improving its modelling so it can be more transparent in showing how it will reach the 2030 target.

He also said the government’s next progress report, which is due before the end of the year, will “have some good news to tell Canadians,” though he would not elaborate.

READ ALSO: Provinces may have to agree to 2035 clean power target to access funding

READ ALSO: Oil and gas sector says new data shows it can both hike output and lower emissions