Robin McGee has been living with stage four colorectal cancer for the past 13 years — a remarkable feat given the seriousness of her condition.

On Wednesday, the 62-year-old Nova Scotia resident travelled to Halifax, where she and 30 other cancer patients and survivors from nine provinces talked to researchers about their experiences with something called precision medicine. It’s an approach tailoring treatment for individual patients, taking into account the genetic make-up of each tumour and the personal characteristics of each patient.

For McGee, this data-driven approach to cancer research and treatment has been life-changing.

“My cancer was like a freight train, and this precision medicine slammed on the brakes,” she said in an interview after taking part in a series of discussions organized by the Terry Fox Marathon of Hope Cancer Centres Network. “It’s prevented very serious pain and disability.”

McGee said she had run out of treatment options paid for by the province. At her own expense, she arranged to have her tumour subjected to a genomic analysis, which would tell her about its mutations. The results pointed to an unusual therapy: a drug typically used to treat other forms of cancer.

After purchasing the drug in Bangladesh, she started treatment in July with her oncologist’s approval.

“My cancer blood markers have plummeted, showing I was responding (to the medication),” she said. “If we could make cancer treatment … responsive to individual biomarkers of mutations, as in my case, we’d save a lot more lives.”

When the cancer centres network was established in 2019, it brought together Canada’s leading cancer hospitals and research universities for the first time. The organization has been described as the “Team Canada of cancer research.”

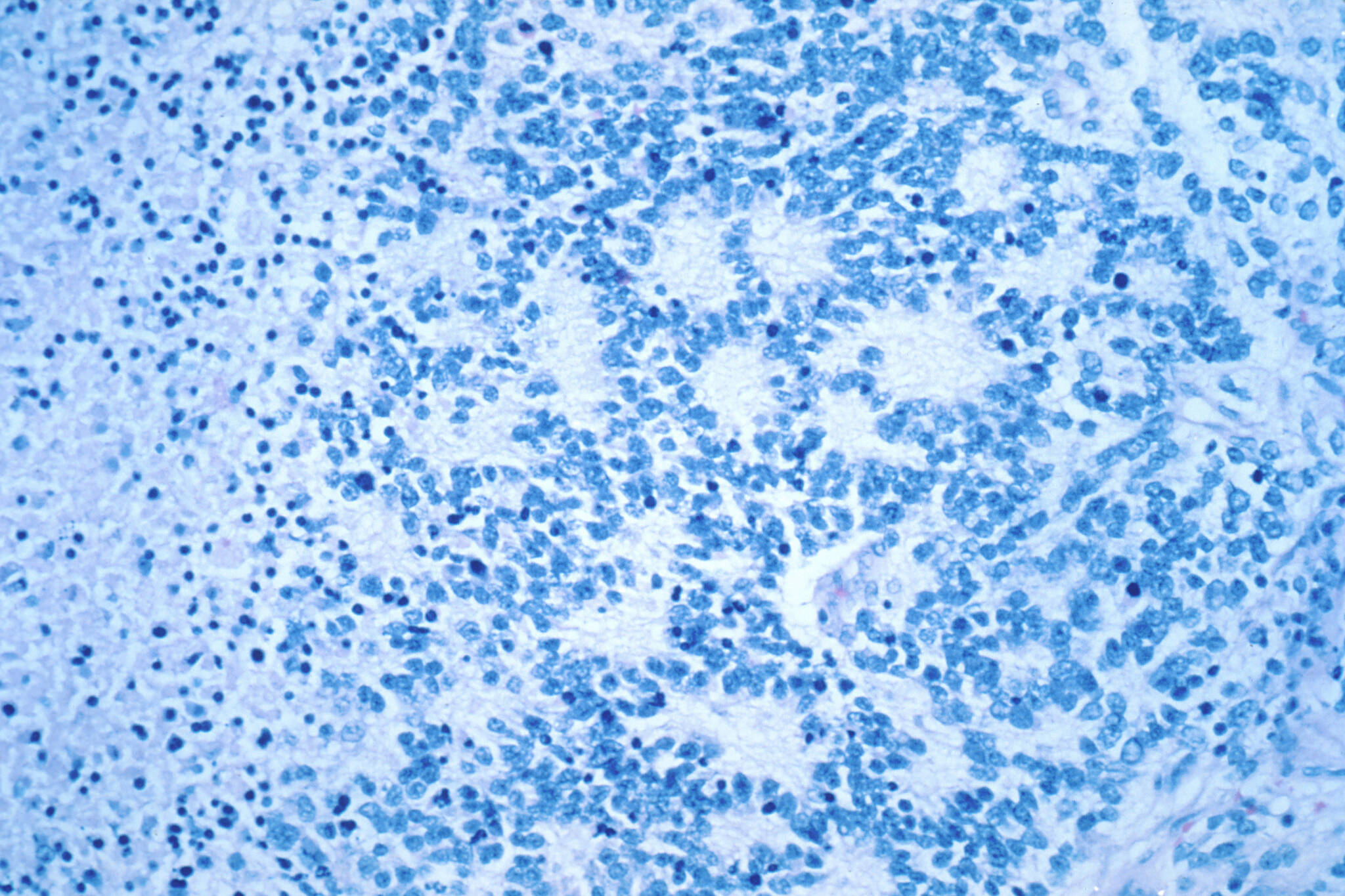

With advanced research focused on finding harmful genetic mutations, the network has been hard at work sorting harmful mutations from benign ones by compiling genetic profile data from patients across Canada.

In the past, this kind of data sharing was hindered by provinces’ reluctance to transmit sensitive health information across borders. The network now provides a secure platform.

“We are building Canada’s most comprehensive resource when it comes to cancer,” said Robin Urquhart, co-leader of the Atlantic Cancer Consortium, which is part of the network.

“It includes clinical data and genomic data from patients across the country. That allows us to do a lot of things, like identifying different markers in blood that can detect cancer earlier …. (Precision medicine) is about being able to match every cancer patient to the best treatment possible.”

Urquhart said the meetings in Halifax marked the first time researchers within the network gathered with cancer patients, survivors and caregivers to talk about the future of precision medicine.

“This group has come together … to help guide our work,” said Urquhart, an associate professor in the department of community health and epidemiology at Dalhousie University in Halifax. “We want to make sure that the work we’re doing aligns with what patients want.”

Urquhart said she wanted to learn from patients and their relatives about their experiences with precision medicine and what might prevent some from taking part.

“They have the biggest stake in this data,” she said.

As for McGee, she has no doubt about its value.

“It is the wave of the future,” she said. “The miracles of today can be the standard of care tomorrow.”

READ ALSO: Lung cancer kills fewer Canadians, early detection, fewer smokers credited