By Anna McKenzie, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Researchers at the University of Manitoba (UM) have released a report that combats what they say is a new strain of residential “school” denialism.

The report, released on Oct. 11, debunks conspiracy theories about a so-called “mass grave hoax” — a narrative that is “not supported by the evidence,” according to researchers Sean Carleton and Reid Gerbrandt.

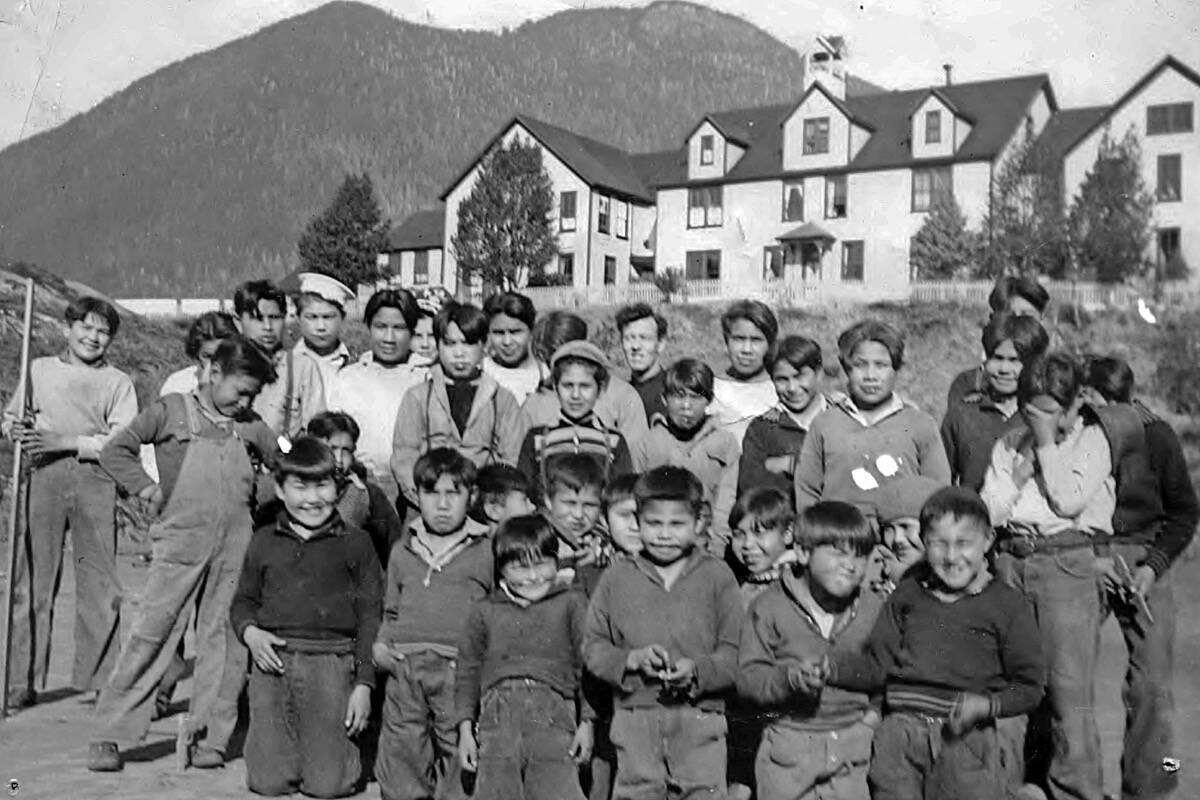

The research involved fact-checking 386 news stories that were published in the six months following the news that evidence of unmarked burial sites was identified on the grounds of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School.

The news unleashed a national reckoning around residential “schools” and led to many similar uncoverings across the country. However, it also led to a slew of denialists decrying the investigations as a “hoax.”

UM’s report ultimately found that there is no truth to claims that media, government and First Nations purposefully misreported potential unmarked graves at former residential “schools” as “mass graves” for political or ideological reasons. The report also found that of the 135 news articles that contained inaccuracies, only 25 used the term “mass graves” when referencing the discoveries.

To learn more about this research, IndigiNews had a conversation with Carleton, who is a non-Indigenous assistant professor in the Department of History and Indigenous Studies at UM, and author of the book Lessons in Legitimacy: Colonialism, Capitalism, and the Rise of State Schooling in British Columbia.

The following Q&A has been edited for length and clarity.

Anna: Can you tell me why you think it’s important to debunk myths about these “discoveries” at Canada’s former residential “schools”?

Sean: I think in the last number of years since the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) final report, and especially since the Kamloops 215 announcement, we’ve seen a concerning rise in residential school denialism.

To be clear, it’s not that people deny that residential schools happened, but rather, denialism is a strategy to downplay, twist and misrepresent basic facts about something — to shake public confidence. In this case, it’s shaking confidence in survivor testimony, and the experiences of many students in residential schools.

I think some people don’t realize how damaging denialism is for the people who have spoken their truth, and I also think that’s exactly why denialists do it. They’re trying to intimidate, discredit and come up with a sort of backlash argument or counter narrative to try and slow the progress on truth and reconciliation in this country. That kind of misinformation and disinformation needs to be confronted head on.

A: That’s really well said, thank you so much. Can you tell me more about why you chose to focus your research on this topic?

S: I made a commitment to a family member who attended the St. Michael’s Indian Residential School in Alert Bay, B.C, that I would use my energy to understand more about residential school history. This motivated me to get involved in helping other settler Canadians, like me, to understand more about the history of colonialism and schooling.

As a historian, I teach classes on residential school history, literature, and help people understand the truth that survivors have been telling us, and what we understand from the church and state records about the system. I think for me, I started to realize that there were people out there who didn’t just not know about residential schools, but would prefer not to know and are actively trying to undermine any changes in terms of Indigenous and settler relations.

I felt like I had a direct responsibility as I saw this misinformation as an affront to the work that survivors have done. The TRC final report formula was very clear — we have to have truth and then truth will lead to healing injustice. Healing injustice will lead to reconciliation. I think denialists understand that formula and what they’re trying to do is undermine people’s truth so that they don’t have to do the healing injustice and reconciliation part. I think we all have a responsibility to ensure in this age of misinformation that that doesn’t happen, and that we don’t miss this opportunity to learn from survivors.

A: Thanks, Sean. On a personal note, challenging misformation is important to me not only as a journalist, but as the daughter of a day “school” survivor. I appreciate the work that you are doing, particularly how the report analyzes how “Canadian” news outlets reported on the news of the evidence of 215 unmarked graves in Tk’emlups.At IndigiNews, we actually halted all reporting until the community was ready to share with us. We wanted to honour grieving protocols, and to not “parachute in” to get a story, causing harm to those who are already grieving. In a lot of ways, it felt like the whole media world was looking to us, as Indigenous reporters, because they didn’t know how to report on residential “schools.” We’re still in the infancy of, you know, being able to tell these stories and tell the truth. I think combating any kind of denialism is really important.

S: The other part of the report that I think is important is that we noticed a new strain of denialism emerge about a year after the Kamloops announcement. Claims that journalists universally misreported to shock and guilt Canadians into caring. I knew that in my gut, people were confused about what was really happening. Even I didn’t really understand the difference between a large number of potential or likely unmarked graves and the mass graves. I didn’t understand the precision in these definitions and even made mistakes myself in terms of figuring out what was being identified here. However, I had a feeling that the people who are trying to discredit the final report of the TRC are now pushing this “mass grave hoax” narrative, so we fact checked this argument through looking at the world’s media coverage following the Kamloops 215 announcement. We found that overall, the majority of journalists in a very confusing time in a breaking news situation actually got it right.

Twenty-five of the 386 articles we examined used the terminology of “mass grave”, representing just 6.5 per cent of the samples we looked at. However, this research took us a year to do, and during that time, the “mass grave hoax” narrative floated around, and now people are picking it up and running with it, and using it as a weapon. We saw the counsellor in P.E.I who put a sign on his personal property for National Truth and Reconciliation Day doing just that. And so, I think we all have a responsibility to do the work, to look into the sources and say some people made mistakes, but they were a minority of mistakes. The amount of mass grave reporting was minuscule, and what we then see as a result is just another example of denialism.

A: I recall noticing that shift too, about a year after that devastating news broke. People were coming up to me in the street to apologize, openly weeping for not knowing about residential schools. Everyone had orange shirts hanging in their windows, and along the highway here on “Vancouver Island.” Not even a year later, all of those orange shirts came down during the Freedom Convoy debacle, and were replaced with Canadian flags. It felt like our pain and grief was forgotten about, and worse, being denied.

S: This is why we felt that the research we’ve done and that the report is necessary because denialism is a backlash. It is trying to push back things. And what we wanted to do was model what pushing back against that backlash could look like it’s like so it doesn’t always have to fall on the shoulders of survivors. That work doesn’t always need to fall on Indigenous people. Reconciliation is not an Indigenous problem. It is a Canadian responsibility, and when truth, that becomes part of your responsibility to hold space for that. What I’m witnessing is that all of these denialists are trying to push back on that and trying to prevent progress. I’m hopeful that if people, and I’m specifically speaking to non-Indigenous people, can learn to identify and confront denialism, it can help. It requires people who have positions, whether it’s in journalism, academia, or policy, to find ways to push back against denialism so that we can continue to move forward with truth and reconciliation.

I hope that there will be more research done on this to give people the evidence to say that the “mass grave hoax” is a misrepresentation of what journalists actually reported. We all have a responsibility during an age of misinformation .125so.375 that we don’t miss the opportunity to learn from what survivors are telling us.

A: Thank you so much for the gift of your time, Sean.