Three experts on toxic drug poisonings diagnosed B.C. with a collective failure and prescribed a sense of urgency in dealing with the crisis, that has claimed more than 11,000 lives since 2016.

B.C. Chief Coroner Lisa Lapointe joined the First Nations Health Authority’s acting chief medical officer Dr. Nel Wieman and B.C. Centre on Substance Use’s co-medical director Dr. Paxton Bach Tuesday (Jan. 31) morning to provide an update on the number of illicit drug-toxicity deaths in B.C.

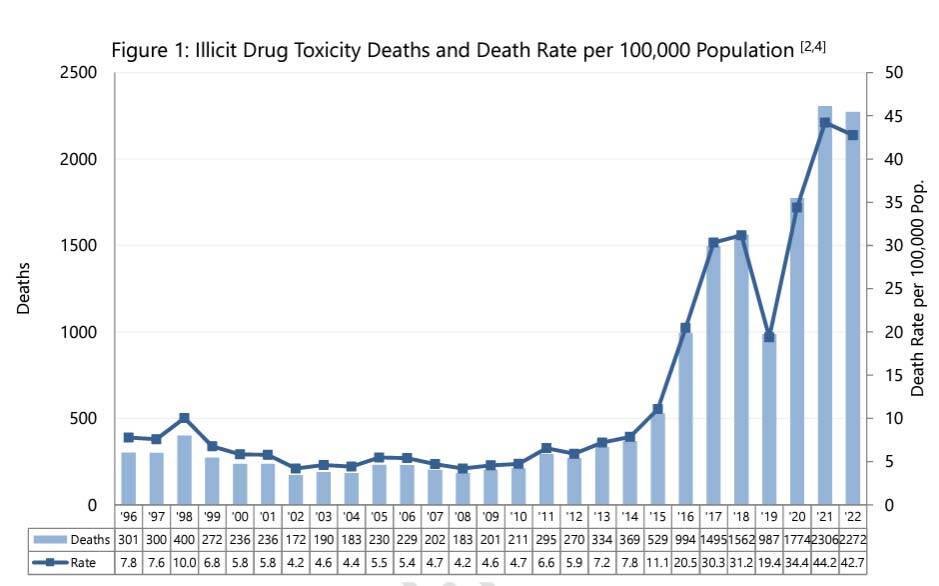

Hours earlier, the BC Coroners’ Service announced that 2022 was the second deadliest year of B.C.’s toxic drug crisis on record. Preliminary results show 2,272 people died from poisoned drugs last year — 34 deaths short of 2021’s record total.

“These numbers represent people — people who were loved, who were valued and who are now greatly missed,” Lapointe said. “These deaths were preventable and their lives matters.”

She called for a “sense of urgency” when asked to assess what is needed beyond promises made by the provincial government. “This is an urgent challenge…we are losing six people every day and have for the past two years and for many years before that.”

Bach also called for greater action. He recognized that many people are desperately trying to change things, but said that every level of government is failing so far.

“The reality is that every year we are back here and every year more people have died.”

Society has not yet decided to address this problem as the emergency that it is, Bach added. “I don’t want to point fingers at anyone, but our response has been inadequate across the board.”

READ ALSO: ‘Dangerous’ to think B.C.’s decriminalization plan will reduce OD deaths: researcher

Wieman struck a similar note.

“We really have to be open and upfront about why… we are not treating this with the same urgency and the same resourcing as we did the COVID-19 pandemic. We have a very stereotyped idea in our heads of who uses substances…we need to bridge that distance, because we are all the same in this toxic drug crisis.”

Lapointe said B.C. needs a strategy that bundles available resources. This means a safer supply of drugs to reduce harm, drug-checking services, Naloxone and overdose prevention sites.

She added there needs to be a continuum of care, so people can access safe drugs when needed, and treatment when they are ready for it.

Another necessary measure is decriminalization to reduce stigma around drug use, she said. This came into effect as a three-year pilot project on Tuesday, with people now allowed to carry 2.5 cumulative gram of illicit drugs for personal use.

The majority of other recommended measures have yet to be really implemented, though.

The latest coroner’s numbers released Tuesday show just how bad things have gotten in recent years.

Records go as far back as 1996 when 301 people died. Between then and 2015, annual fatalities ranged between 172 and 529, until 2016 when 994 people died. It was in April of that year that B.C. declared the opioid crisis a public health emergency.

Since then, more than 11,000 people have died.

The fatalities continue to concentrate in urban centres. In 2022, 562 people died in Vancouver, 232 died in Surrey and 157 died in Victoria.

Looking at death rates paints a different picture though, with a disproportionate level of fatalities occurring in some rural areas. The highest death rate per 100,000 people in 2022 was still in Vancouver (centre north) at 470.8, but from there it went to Terrace at 110.5, Merritt at 92.6 and Hope at 87.9. By health authority, Northern Health had the worst rate.

The majority of those dying continue to be men. In 2022, they accounted for 1,784 of the 2,272 toxic drug supply deaths.

By age, people between 30 and 59 are the most at risk. They made up 1,139 deaths in 2022. Just 34 people were aged 18 or younger and 29 people were aged 70 or older.

Where people use drugs continues to be a point of interest and concern. The BC Coroners’ Service found 55 per cent of toxic drug deaths in 2022 occurred in private residences, bucking the myth that people are only dying on the street. Another 23.6 per cent of deaths happened inside other residences, such as shelters, SROs or hotels. Close to 15 per cent occurred outside.

One person died at an overdose prevention site in all of 2022. There is no evidence that safe supply has contributed to any illicit drug deaths.

READ ALSO: What to know about B.C. decriminalizing possession of drugs for personal use – starting today

READ ALSO: B.C. drug advocates cautiously optimistic about decriminalization

@janeskrypnek

jane.skrypnek@blackpress.ca

Like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.