Alexandra Mehl, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter HA-SHILTH-SA

Tuesday, Feb. 14, marked the 32nd year that the streets of the Downtown Eastside flooded with remembrance of murdered and missing Indigenous women, girls, and gender diverse peoples.

Families from First Nations across Canada came to commemorate their missing and murdered loved ones.

At the corner of Main and East Hasting Street people began to gather in the morning, organizing for the day’s events. The sky was widely blue, and the air was crisp with a coastal winter bite.

Signs hung from tents with the faces and names of missing and murdered women, girls, and gender diverse people. Repeating the phrase, “In loving memory of…”

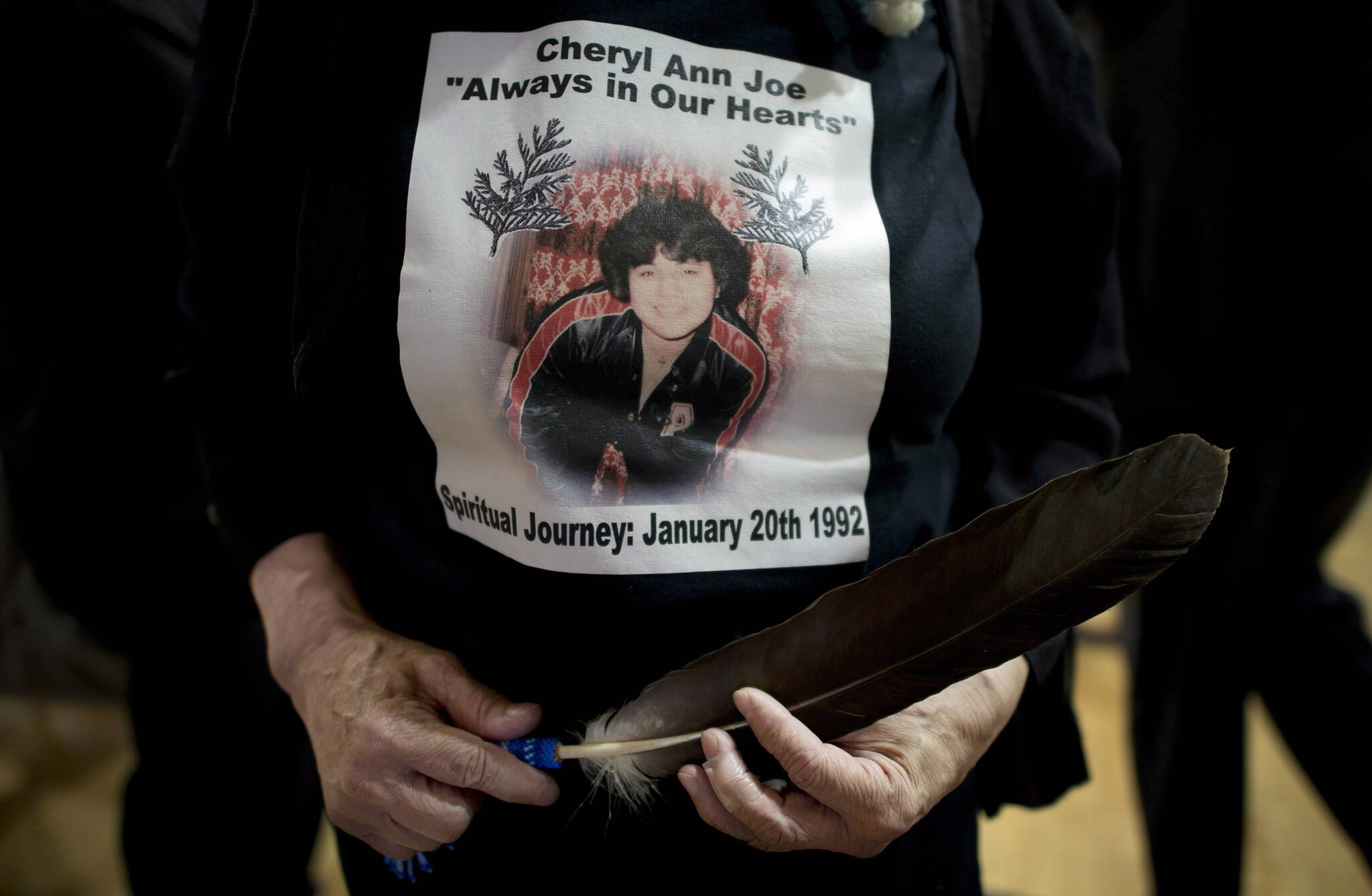

The Women’s Memorial March in DTES began in 1992 after the murder of Cheryl Ann Joe on Powell Street.

In a press conference on Feb. 14, Melodie Casella, cousin of Cheryl Ann Joe spoke.

“The spark of this March is to continue to bring the awareness of the murdered and missing woman in Canada,” said Casella. “I think it’s the families that have to be honored and acknowledged as well. And the ones that stand here with their broken hearts.”

Families of the missing and murdered women, girls, and gender diverse people stood in front of the mic at the corner of East Hastings and Main Street, sharing stories of grief and loss to the crowd of people, that grew larger and larger as the morning went on.

Around them, a sea of posters, filled with the faces of MMIWG2S+ were held above the growing crowd of people.

As family members spoke eagles took their turn flying overhead.

Among the families were Lee and Leah Desjarlais, mother and father of Jenaya who was murdered in 2019 in Regina, Saskatchewan.

“We’re here to help the other families, as well to find some sort of peace to help us with our grieving,” said Leah Desjarlais.

She explained that despite not knowing anyone at the event, many people have come together and shown love.

For Regina and Carson Poitras, their daughter, Happy Charles, remains missing.

“I don’t know where my daughter is and I still look around everywhere,” Poitras said to the crowd. “I’m hoping that we can get some action out there.”

After family members spoke, shoulder to shoulder, the crowds of people walked in song, down the streets of DTES, united in honoring their missing and murdered loved ones, and calling for justice.

Elders led the memorial march, stopping at locations where women, girls, and gender diverse people were last seen or found, murdered in the DTES. They pray in ceremony and lay a yellow rose for those who remain missing, and a red rose for those who have been murdered.

“The roses are getting more and more each year,” said Evelyn Youngchief, an organizer for the Women’s Memorial March Committee.

According to a census released in 2022, Vancouver is home to 63,345 Indigenous peoples, making the city the third highest population of urban Indigenous people in Canada.

The Downtown Eastside has been reported to have a disproportionately high population of Indigenous people.

“The women that live down here are not safe in their environment,” said Youngchief.

The neighborhood, one of Vancouver’s oldest, is interwoven with high levels of addiction, sex work, homelessness, among other social issues that put its residents at risk of violence.

“The violence is getting worse,” said Youngchief. “It’s like nobody cares.”

“After three decades the MMIWG2S+ continue… to increase, despite the National Inquiry,” said Chief Judy Wilson at the press conference.

The Squamish Nation matriarch, Kwakwaýel Simia Wendy Nahanee, has sat on the planning committee for the memorial walk in DTES for five years, and has been a resident of the area for over twenty. In an email to Ha-Shilth-Sa Nahanee notes that Indigenous women living in DTES are blamed for the violence that is committed against them because of their `high risk’ lifestyles.

The Downtown Eastside Women’s Center sees over 1,000 women and girls through their doors seeking their supports each day, with 70 per cent of their clients identifying as Indigenous.

Nahanee said not only is this a walk to remember those who have been lost, but is a march “against class disparity, racism, inequality and violence.”

Coordinators of the walk publish a booklet annually which includes a list of names of Indigenous women, girls, and gender diverse peoples who are missing and murdered. Since 1992, the year of the first annual women’s memorial walk through DTES, over 1,500 Indigenous women’s names from DTES have been added to the list, wrote Nahanee.

“I was born Indigenous, I will die Indigenous, but I don’t want to die because I am Indigenous,” said Nahanee.

RELATED: ‘National shame:’ Groups decry inaction on violence against Indigenous women, girls

RELATED: ‘An ongoing crisis’: B.C.’s missing and murdered Indigenous women honoured in Victoria