As climate change forces the rapid retreat of glaciers across B.C., scientists say there is one potential silver lining: freshly exposed habitats for salmon. But it isn’t just conservationists who are considering the possibilities the melting ice presents.

A new study led by Simon Fraser University researchers finds that mining companies are interested in the areas, too, and that B.C. laws are allowing them to stake claims on the land without consulting First Nations or considering long-term environmental implications.

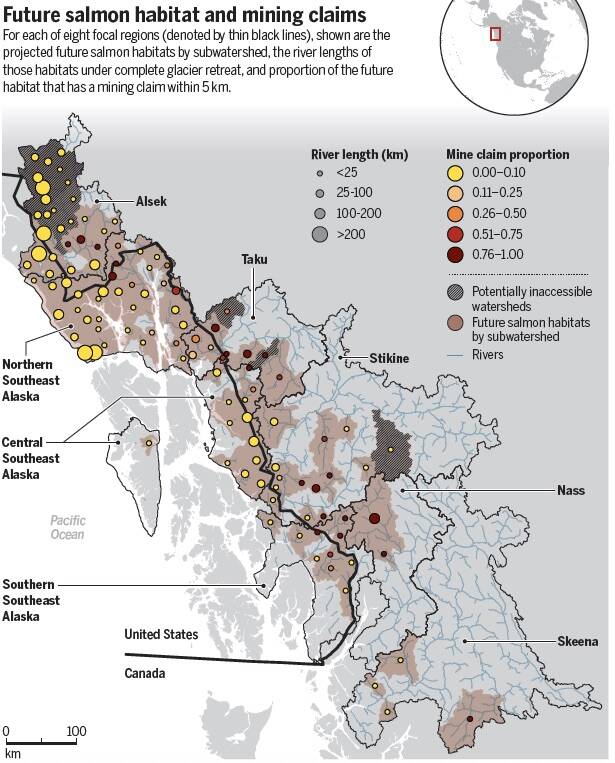

The paper, published in Science this week, identified 4,973 kilometres of future salmon habitat in northern B.C and southern Alaska. Of the area, 564 km are near current mining claims and 286 km have claims directly on them.

SFU professor and study lead author Jonathan Moore says that area of overlap is likely to only increase, with 53 per cent of B.C. future salmon habitats assessed as having high or medium mineral potential. Moore recognized not all claims are sure to be developed, but said those that are may pose a serious risk to future salmon populations.

“Mining has a history of, in some cases, causing profound harm and damage that’s far reaching and long lasting,” said Moore, who is the head of SFU’s Salmon Watersheds Lab. This, he said, can include digging up and destroying habitat, using explosives to remove ice, sucking up large quantities of water from local rivers and streams, and emitting pollution.

“Mining mobilizes a lot of toxins that are otherwise locked up in rocks. And sometimes they actually introduce new chemicals like cyanide as part of their processing.”

In an interview with Black Press Media, Moore added that as permafrost melts and glaciers retreat, landscapes become increasingly mobile and pose challenges to the mining process and environmental mitigation.

READ ALSO: B.C.’s iconic Kokanee Glacier is melting and it can’t be saved

The paper acknowledged that mining can contribute to important low-carbon technologies, but noted that the majority of claims in southern Alaska and northern B.C. appear to be targeting gold – a mineral still used primarily for jewellery.

It said if governments wants to give salmon a chance in the future, they need to start considering how climate change will alter the land and what environmental values need protection now to ensure their existence down the line.

One of the primary barriers to this in B.C. is its free-entry mining claims process, which allows anyone to place a stake on a chunk of land simply by going online and paying a small fee – $1.75 per hectare. No environmental assessment or consultation with First Nations is required at this stage and companies are allowed to do exploratory work before going through any approval process.

It also becomes extremely difficult to protect the land once it’s been claimed, unless a mining company gives up their stake or agrees to have it bought out by the province.

Such a situation arose several years ago when the Gitanyow First Nation in northwestern B.C. asked the province to expand a conservancy that partially covered their territory. It was only then that the Nation discovered multiple mining claims had been laid throughout their lands without their knowledge, making extending the conservancy to cover multiple salmon spawning streams impossible.

Gitanyow launched a lawsuit against the Chief Gold Commissioner of B.C. and, in September of this year, the B.C. Supreme Court ruled that the province has 18 months to reform the Mineral Tenure Act to include consultation with First Nations at the claims stage.

Naxginkw Tara Marsden, a representative for Gitanyow Hereditary Chiefs and a co-author of the study, said salmon have been part of their way of life for a millennia, and serve vital purposes both culturally and in terms of food security. Protecting the land is not just about their right to do so, but their responsibility to pass on the territory to the next generation in as good as or better condition as they found it – a belief encapsulated in the word “Gwelx ye’enst,” she said.

“Nature is giving us a second chance to get it right.”

Unable to expand the conservancy on their lands through the province, Gitanyow declared the 54,000 hectares they sought to safeguard an Indigenous Protected Area in 2021. In August 2023, the community issued its own management plan committing to “the health of the salmon populations, waters they inhabit, and wildlife and plants relied upon by Indigenous and non-Indigenous people alike.” The province has yet to recognize the protected area.

Moore said it is this kind of forward-looking work by Indigenous governments and groups that makes him hopeful.

“That’s really one of the places where there’s exciting progress happening.”

He said he’s also heartened by a few recent steps by the province. This month, the Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship released a draft framework on biodiversity and ecosystem health, with its stated intent to make conservation an “overarching priority.”

In it, the ministry says: “The Framework sets the stage for the desired transformational shift from a land management system that prioritizes resource extraction (subject to constraints) to a future that is proactive, prioritizes the conservation and management of ecosystem health and biodiversity, and is implemented jointly with title and rights holders (a paradigm shift).”

Moore also pointed to a $300-million First Nations-led conservation fund B.C. announced in October, and the $1-billion conservation framework agreement signed by the province, federal government and First Nations Leadership Council in November. B.C. has said it intends to protect 30 per cent of the province’s land base by 2030.

READ ALSO: B.C. creates $300 million fund for First Nations-led forest conservation

READ ALSO: $1-billion agreement to ‘fast track’ old-growth, habitat protection work in B.C.

Moore said what he would really like to see, though, is a shift in environmental laws and policies that recognizes the transformations climate change will bring and that governments now have an opportunity to significantly shape things for the future.

“It’s this really important societal decision that we’re staring at. The ice’s edge is retreating and these new ecosystems are being born. How are we going to use them? Are we going to dig them up for gold or are we going to steward them for salmon and all that salmon do?”

Black Press Media reached out to the province for comment, and will update accordingly.