It’s been nearly five years since Noah Peppin has had one of the life-threatening seizures that plagued the first two years of his young life – but his mom knows one could still strike at any time.

So it was devastating to learn, says Stephanie Vazquez, that if one were to happen at school now, odds are slim her feisty, yet shy, son will get the life-saving medication he’ll need in time.

“With zero exception to the rule… he is now at school for six hours a day with no rescue medication. If he has a seizure that lasts longer than three minutes he needs rescue medication,” the South Surrey mother said.

“What if the ambulance doesn’t arrive within three minutes? What if they don’t have what he needs?”

Vazquez said her family was notified last month that Noah, who was has Sturge-Weber Syndrome (SWS), no longer meets the criteria for the Ministry of Health’s Nursing Support Services (NSS).

Given his risk of seizures – he remains on anti-seizure medication – he had been assigned a nurse through the program when he started school at Sunnyside Elementary two years ago. Such nurses work with parents on a care plan and with the school to train staff on how to administer rescue medication, what a seizure might look like, etc., Vasquez said.

READ ALSO: Construction phase begins for South Surrey’s Sunnyside Elementary addition

According to the March 31 letter, however, students are now discharged from NSS “when seizures no longer require interventions beyond seizure first aid and/or no interventions beyond seizure first aid occurred in the previous year.”

“They remove them from the program, saying it is difficult to retain how to administer rescue medication if they (staff) are out of practice,” Vasquez explained.

“Does that mean I can never leave my house when he’s at school?”

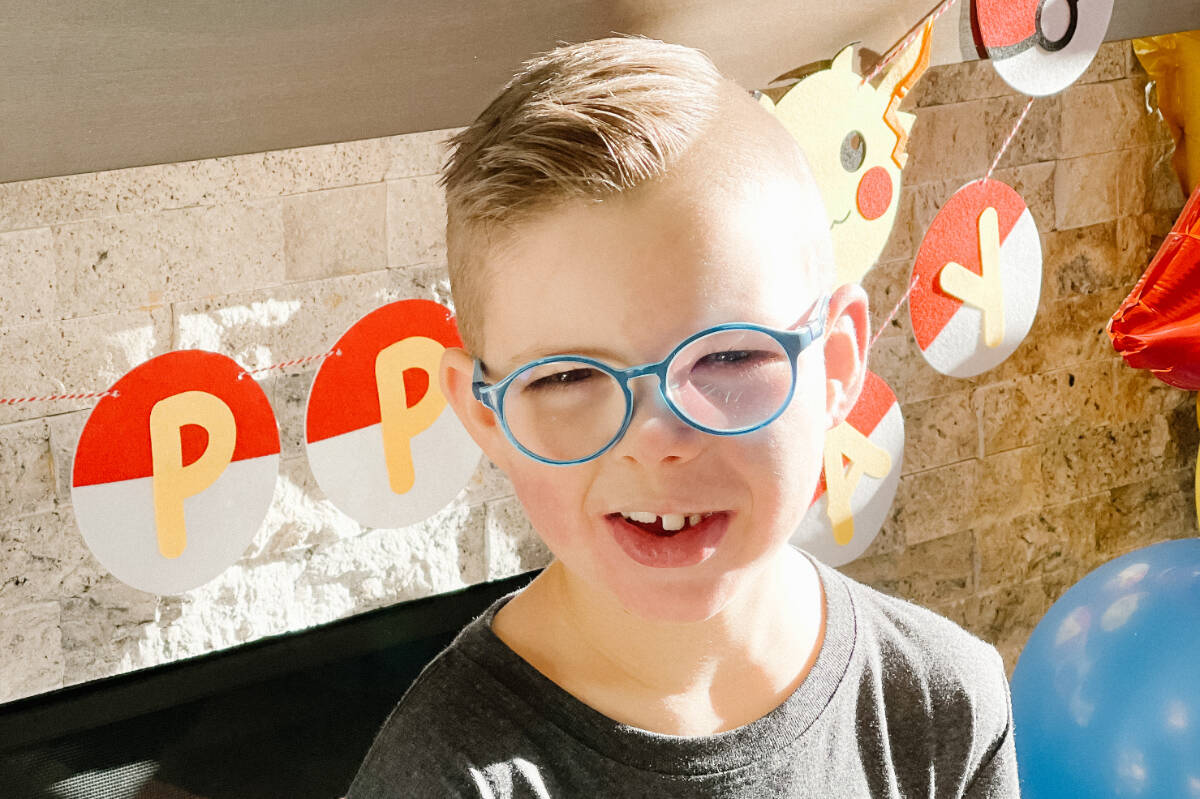

Noah, 7, was diagnosed with Sturge-Weber Syndrome at two months old, though doctors immediately suspected the rare vascular condition at birth, given the large port-wine birthmark that covered much of his face.

Of the three types of SWS, Noah has the most common, said Vazquez. In addition to the birthmark, the progressive syndrome is characterized by seizures, glaucoma, developmental delays and weakness to one side of the body.

At one time, Noah’s family didn’t know if he would ever walk or talk. Vazquez remembers watching his eyes deviate and his face turn blue during the first of his “countless” seizures, at five-and-a-half months old. During another, at two years old, he stopped breathing.

These days, fortunately, Noah appears much like most other kids his age, with beating his dad at Pokemon, taking his dog Milo for walks and practising jiu jitsu among the many things he revels in, and broccoli on the polar opposite side of the spectrum.

He hasn’t let SWS define him, his mom proudly highlights in one of the Facebook posts documenting his journey.

But Vazquez said it’s not right that her son can no longer feel safe at school.

“This is discrimination and wrong,” she said. “The system is broken and not built for children unless they fit in a neurotypical box. This needs to change.”

She also worries about trying to wean him off of his anti-seizure medication, “now knowing he may not have the intervention should he have a seizure.”

Vazquez said she has reached out to her MLA, as well as the Surrey School District superintendent regarding her concerns. As of Tuesday morning (April 19), she was waiting on a letter from her neurologist to share with the MLA, and received notice that an assistant superintendent with the district would reach out to her this week.

Peace Arch News reached out to the Ministry of Health for comment but did not receive a response by press deadline Tuesday.