A class of second-year design students at Emily Carr University are waiting with anticipation to see if their inventions will be manufactured and sent to a refugee settlement in South Sudan.

The students were tasked this semester with putting their skills to a very real test: to create an interactive object that will help children living with trauma to process their experiences and find joy.

Designer and instructor Christian Blyt has been collaborating with non-profit The Power of Play for several years now to help build playgrounds for children in various parts of the world. The non-profit itself says it has built over 35 interactive playgrounds in eight countries since it was founded in 2017.

This year, though, the non-profit’s founder and CEO, Reza Marvasti, wanted to do something a little different. He has spent a lot of time in South Sudan in recent years and seen the impacts of civil war and ethnic violence there. Too often, Marvasti said, children are being forced into becoming soldiers or labourers or being trafficked for sex.

Most recently, clashes between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces, since April 2023, have forced the displacement of some eight million people, according to the United Nations.

Many who have fled the war have ended up in refugee settlements. One of those places is the Gorom settlement, located near South Sudan’s capital of Juba, where Marvasti said around 1,200 children are living. Basic necessities are hard enough to come by there, let alone toys or means of play, Marvasti said.

“The idea of kids not playing and never having the opportunity to play is kind of alien to us, it’s hard to comprehend. But this is what is happening.”

Bringing a playground into such a transitory place didn’t see practical, but Marvasti and Blyt decided sending individual toys or interactive objects was. So, when students entered Blyt’s studio class in January, he presented them with the challenge.

Blyt instructed them to break into groups of three and then presented them with the design brief. The creation had to be an interactive object for children living with trauma, that they could use alone or with others. How would it bring joy, contemplation, reflection and teamwork? Blyt asked his students.

The design also had to be durable, manufacturable and made primarily of plywood. And, it had to be completed in about eight weeks.

Design trio Saanvi Bhat, Joey Kim and Tai Vo said the project immediately inspired them and their classmates. The idea that they could make a positive impact in the world drove them to put in 12-hour days and work late into the night on numerous occasions.

“We were just working so hard. We were not talking about grades, I don’t even think we care about our grade right now,” Bhat said.

“I felt more responsibility of really putting more effort into this,” Kim added.

The object they came up with is comprised of six wooden pentagons that can be fitted together in different formations and a serious of colourful blocks that slide into holes drilled into the pentagons. The design trio also played around with rolling beads through the structure, which they said kids in Sudan can easily make themselves out of red clay. The object, called “HIVE,” is intended to spur imaginative play and can be interpreted and played with however kids choose.

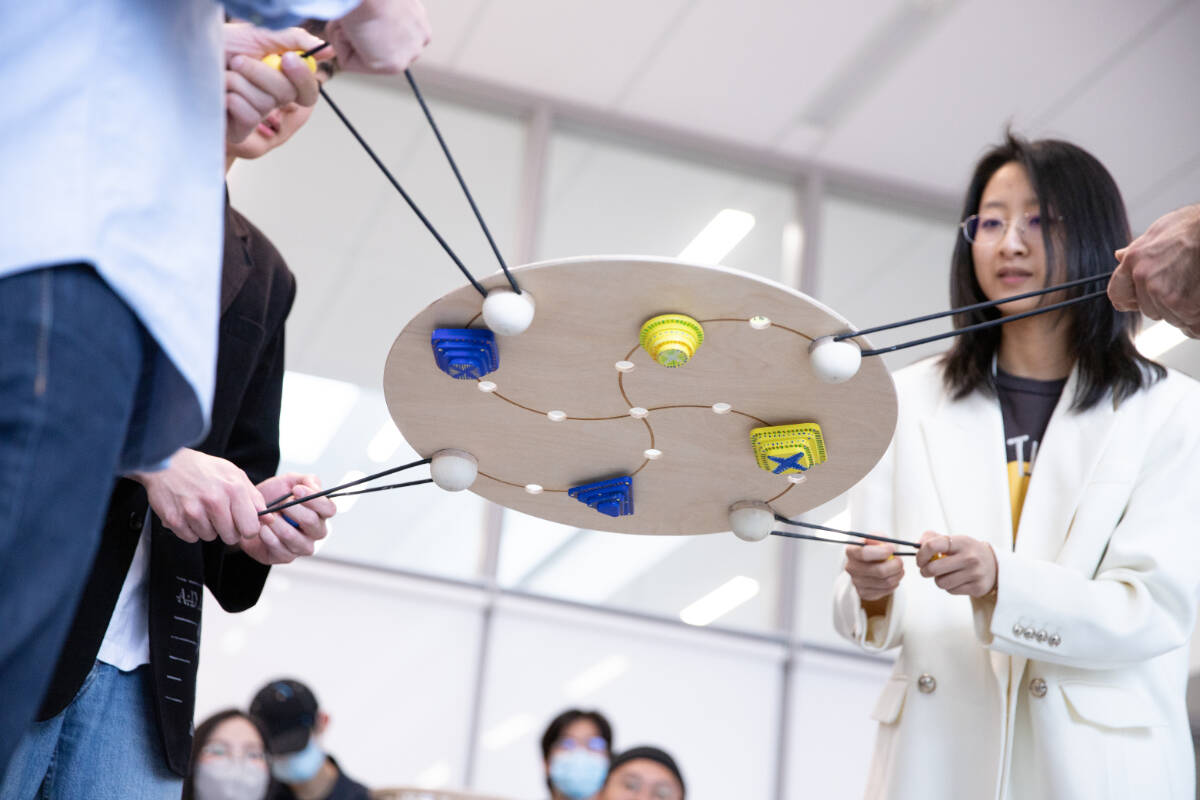

The six other design teams – or studios, as Blyt calls them – came up with other forms of play. One studio invented a kind of balance board, which up to four people can collectively use to move a ball through a maze located at the centre. Another of the trios created a large-scale spinning top, while a different group incorporated stone tossing with balance.

Each of the objects is now off for testing with University of British Columbia psychology professor Benjamin Cheung and his students. They plan to introduce the designs into some kindergarten classes around Vancouver to try and quantify their impacts.

Some tweaks are likely to be made and then, if each of the objects is able to be manufactured, they will be shipped off to South Sudan later this year.

Blyt said the project is an indication of how industrial design has been changing in recent years, as the profession comes to grips with the fact that they need to create better things for a world enduring conflict and climate change.

“We’re running out of time and we have a huge responsibility as designers to make a positive contribution, not just an economic contribution, to society.”