A B.C. startup is looking to begin the testing stage in Scotland for an underwater turbine that could be one of the most efficient and sustainable energy models on the global market.

Dorn Beattie, a self-described “wacky inventor” and former chart topping musician, created the Swordfish turbine around 2018 when he was looking to create an alternative to a gas-powered generator for his boat.

“I came up with an idea for a generator with the original version of Swordfish”, he said. “When I originally developed it, which was a little more pointed and only designed to go in one direction, the goal was to tow it behind my boat and bypass the alternators on the boat, which in theory would give me a ten per cent increase in horsepower, and reduce the gas consumption.”

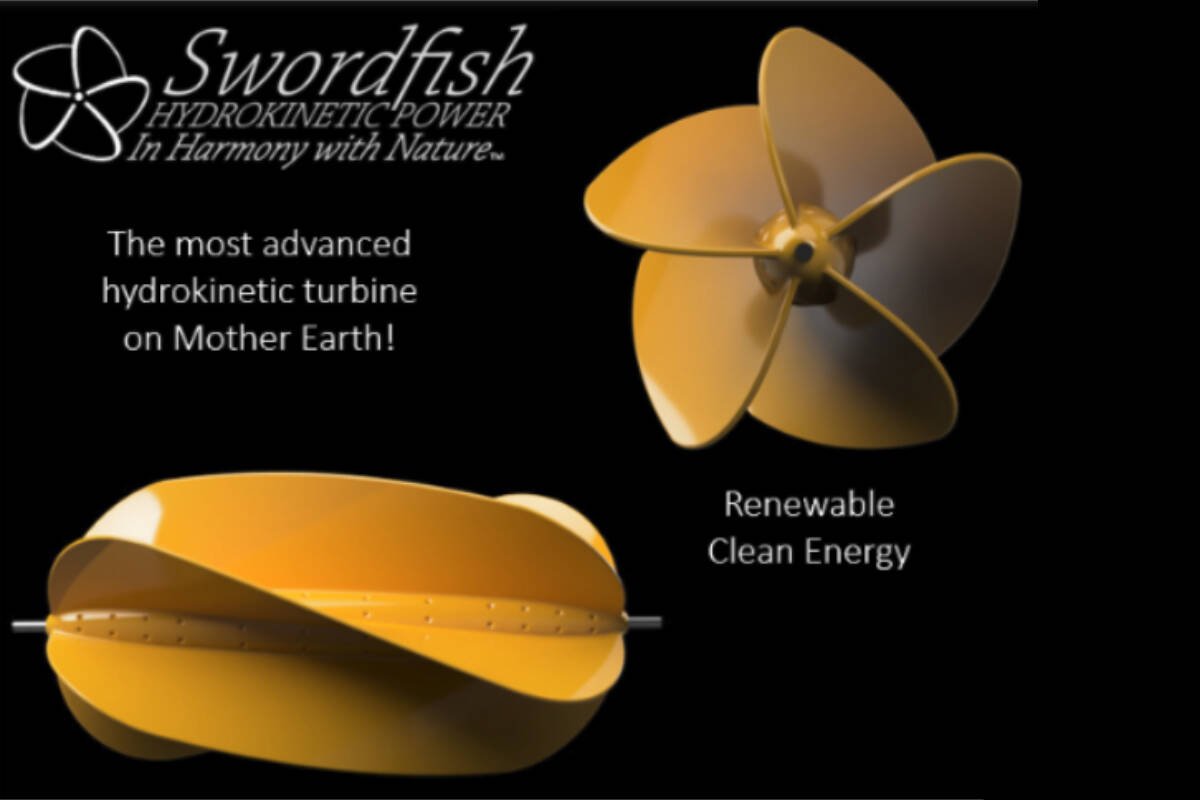

Over the past few years, the design grew into a horizontal axis, bi-directional turbine that can produce up to two megawatts per device, which could power around 1500 homes.

The corkscrew-shaped device, which can be between three and 12 metres in length, sits under the water and uses water currents in rivers or the ocean tide to power generators on land.

As opposed to other hydro-kinetic energy devices and sustainable energy models that have tried to make their way into the market, the Swordfish is expected to be harmless to wildlife, it’s quiet, there’s no electromagnetic radiation, and it stays completely out of sight.

Tidal energy is also more predictable that solar and wind, and it’s cheaper to build and operate than nuclear and hydrogen energy.

His inspiration to continue building the Swordfish brand and further developing the turbine for commercial use is his desire to help curb CO2 emissions and diesel fumes which are some of the leading causes to climate change.

He mentioned wanting to use the device in Haida Gwaii, which currently uses three two-megawatt diesel generators that consume ten-million gallons of diesel fuel every year.

“In addition to the the amount of diesel that they consume, it pollutes their air locally, and they can’t grow their town because they can’t add more industry to their towns. So they’re basically stunting the growth of the towns unless they add another diesel generator, and they’re not willing to do that,” he said.

According to Natural Resources Canada, a total of 251 remote communities across the country have their own fossil fuel and 80 of those are in B.C.

Patrick Marshall, the CEO of Swordfish, has worked with local governments and First Nations through B.C. for decades, and he said they have garnered lots of support from multiple levels of government and multiple First Nations across the province.

“We’ve had great support from Canada and British Columbia in terms of the regulators, like Fisheries and Oceans Canada, we’ve been working with their management in Vancouver because we want to make sure they come along and understand how this works,” said Marshall.

Swordfish, which has offices in Victoria and Vancouver, is planning to take the device to the European Marine Energy Centre in Orkney, Scotland for official contained demonstrations, and they continue to facilitate conversations with stakeholders and community members, getting ready for when the device is available for commercial use.

“I served in as the economic developer for Campbell River for 17 years and I would see these technologies show up on a Sunday with a computer composite, and by Wednesday, they were dead in the water because they didn’t actually talk to anybody in the community. So we’re not going to make that mistake,” said Marshall. “I understand the First Nation community process, so we’re going to honour that and make sure that we exceed those expectations. Everybody wants to solve climate change, we want to do it in a responsible and visible way.”

The device has already won multiple awards, and has been nominated twice for Prince William and David Attenborough’s “prestigious” Earth Shot Prize. It was also recently a runner-up for the Centre for Ocean Applied Sustainable Technologies’ Pitchfest contest.

Marshall says they expect the Scotland testing process to last about two months, and they need to finish the nine-step technical readiness process, and their currently at step six. He expects the device will be ready for commercial use in about two years.