A law promising public safety but facing criticism for stigmatizing drug users remains suspended after a court ruled against the B.C. government Friday.

The province had asked for an appeal of the temporary injunction suspending Bill 34 until March 31, but the BC Court of Appeal Friday denied that request with Justice Ronald Skolrood issuing an oral ruling.

The Restricting Public Consumption of Illegal Substances Act limits personal drug possession in certain public spaces, but B.C. Supreme Court Chief Justice Christopher Hinkson Dec. 29 had issued an injunction against the law scheduled to come into effect on Jan. 1.

The Harm Reduction Nurses Association, describing itself as a non-profit Canadian national organization with a “mission to advance harm reduction nursing through practice, education, research, and advocacy” filed a legal challenge in late November to prevent the law from coming into force. HRNA has also asked the BC Supreme Court to declare the law unconstitutional.

Hinkson said in his initial ruling granting the injunction that the legislation “poses a sufficiently high probability of irreparable harm” by pushing drug users into places where it will be less safe to consume drugs.

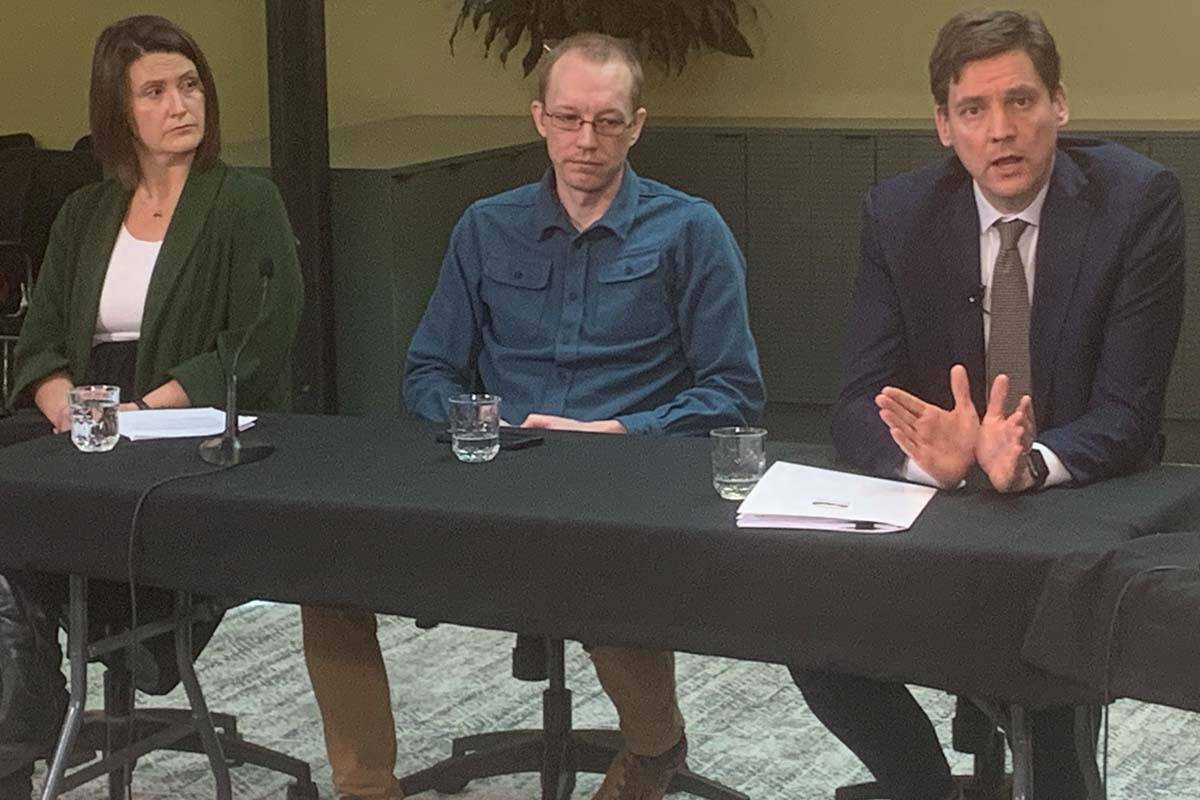

Public Safety Minister Mike Farnworth Monday (March 4) expressed disappointment with the court’s ruling.

“It’s our view that if we can regulate, where tobacco and alcohol or cannabis can be consumed, then it makes sense to us that it should be, where drug use can take place,” he said.

The bill restricts personal drug possession in public spaces in response to concerns among municipal leaders and others about B.C.’s trial exemption from federal illicit drug laws. The trial — which exempts from criminal penalties possession of up to 2.5 grams of certain illegal drugs for personal until Jan. 30, 2026 — started Jan. 31, 2023.

RELATED: Injunction against B.C.’s new public drug use law sparks mixed reaction

At the time, schools were deemed off-limits under federal legislation. New federal measures (following a request from B.C.) enacted Sept. 18 expanded the exclusion zone to playgrounds, spray and wading pools, and skate parks. The provincial legislation tabled in October confirmed these exclusion zones and expanded them.

Farnworth said federal rules in place before the provincial legislation remain in effect. Schools, playgrounds, spray and wading pools, airports and Coast Guard stations remain off limits to public drug consumption under decriminalization. Commercial doorways, bus stops, beaches and what Farnworth called “other parks” are places where drugs can be consumed under the temporary injunction issued in December.

“That was where we are told ‘no’ and that’s what are particularly concerned about, because we think that’s wrong,” Farnworth said, adding his government’s focus lies on winning the larger court case about the constitutionality of the law.

Premier David Eby said he understands the confusion and accused his political opposition of spreading “some misinformation” about the issue.

“But I think British Columbians understand that we can have compassion about addiction and mental health issues, while having standards and rules around where it is and where it isn’t appropriate for drug use,” he said.

He predicted that his government “ultimately…will be successful” in the larger legal dispute.

Eby added B.C.’s goal under decriminalization is to keep people alive and connect them to services. “I’m a strong believer in taking a public health approach to addiction,” he said.

He also touched on Oregon’s recent decision to roll back parts of its decriminalization. While B.C. will continue to watch what is happening in Oregon, as well as other jurisdictions, Alberta and Saskatchewan have seen “massive increases in death,” Eby said.

Ending decriminalization would simply tie up police resources, which could be used to go after drug traffickers, he said.

BC United Monday used Question Period Monday to renew its calls to end decriminalization in holding it responsible for a declining public safety.