For nearly three decades, Michael Guy’s family did everything they could to keep him alive.

His mother Judith advocated for him in doctor appointments, made daily calls to outreach workers and travelled the province to help him get off the streets.

Michael’s older brother, Stefan, worked extra hours to pay for food, winter clothing and the occasional hostel so he wouldn’t be spending every night on the street.

It was a fight Judith and Stefan came to believe was one they were fighting alone, and would eventually lose.

“It has been like watching a terminal illness for all these years take your child, and the world sits back and looks,” says Judith.

Michael was just 14 years old when an injury led to him being given morphine at a hospital. It was the start of a substance-use disorder that ended in a Nelson encampment on June 28, 2023, where he died of a drug poisoning. He was 42.

Judith, who lives in Nanaimo, and Stefan in Vancouver, said they felt compelled to share Michael’s story following the closure of Nelson’s Coordinated Access Hub in March.

Michael was a regular visitor to the Hub since it opened in July 2021, a federally funded program that offered a communal space for clients to access an episodic overdose prevention site, an employment program, housing assistance and other health resources.

It was also, crucially, a safe place for Michael. He used it to catch a couple hours sleep without fear of being attacked or robbed, could be with friends and receive packages from Judith, who would mail boxes of food and clothing to the only address she knew he would be at.

Knowing Michael was at the Hub also offered his family a little relief from the constant and chronic stress over his health and whereabouts.

“Hours and hours of worry,” says Stefan. “It consumes your whole day, your whole week. I think that’s what’s so disappointing about the Hub closing. That was somewhere where if he was really in the shit, he could go there and get a hold of us fairly quickly.”

A spokesperson for the Nelson Committee on Homelessness, which managed the Hub, said it could no longer afford to keep the site open. The downtown location cost $400,000 annually to operate, which was deemed unaffordable after a 10 per cent decrease in federal funding and the end of a $220,000 grant from the Union of B.C. Municipalities.

Jeremy Kelly works for Nelson Street Outreach, a supportive program for those unhoused that operated out of the Hub.

In the weeks since the facility’s closure, Kelly said his team has received a 70-per-cent increase in calls, ranging from reported shoplifting and disturbances to concern for the health of people seen on Nelson streets.

“[The Hub was] a central location. People losing that food service, people losing that clothing; it’s been a huge hole in the street culture.”

“A raw, beaten-up piece of human”

In July 2022, Judith woke in a hostel. She had her breakfast, then began the daily task of searching Nelson for her son.

She’d check Stepping Stones shelter or call Nelson Street Outreach, and if that failed she would wander the streets until spotting him. He had no phone and often changed where he was sleeping from night to night.

Judith, a retired nurse, had experience searching for Michael. When he was 15, Michael completed his first treatment program. He was, Judith was told, “a star of the program.”

But it didn’t take, and shortly after he left the family’s home in Nanaimo for the streets of Victoria.

It devastated the Guy family. Judith began travelling to the city every two weeks to find and check on him, and took solace in the knowledge he was relying on a youth program for food. He also contacted his parents every birthday and holiday with a borrowed phone.

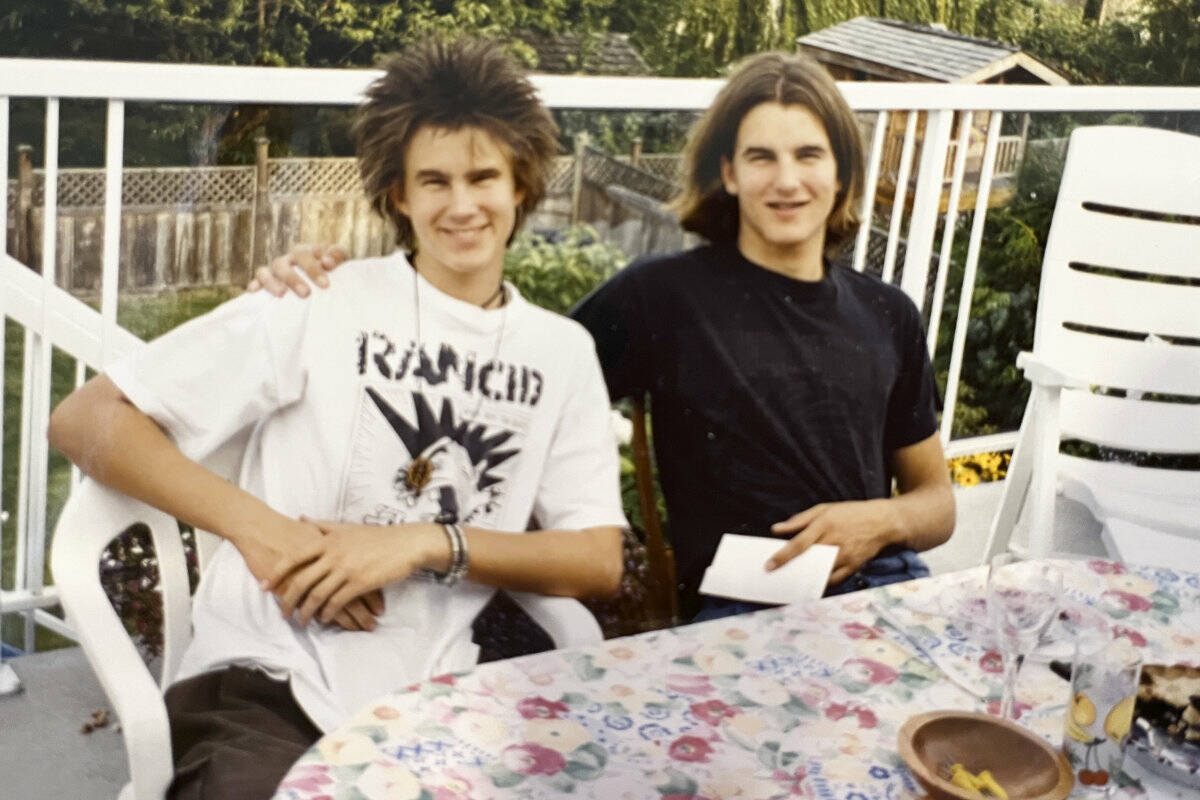

This was the same boy Judith remembers once running away from her in a grocery store to comfort a crying baby. The same teen who was quiet, easy going and a little mischievous. When Michael grew dreadlocks, Judith realized he was only doing it for the $15 his grandparents promised if he would shave them off. Once that was done, he’d start growing them back for the next payday.

“He was a keen observer of what was happening around him, and he had a very dry sense of humour,” she says.

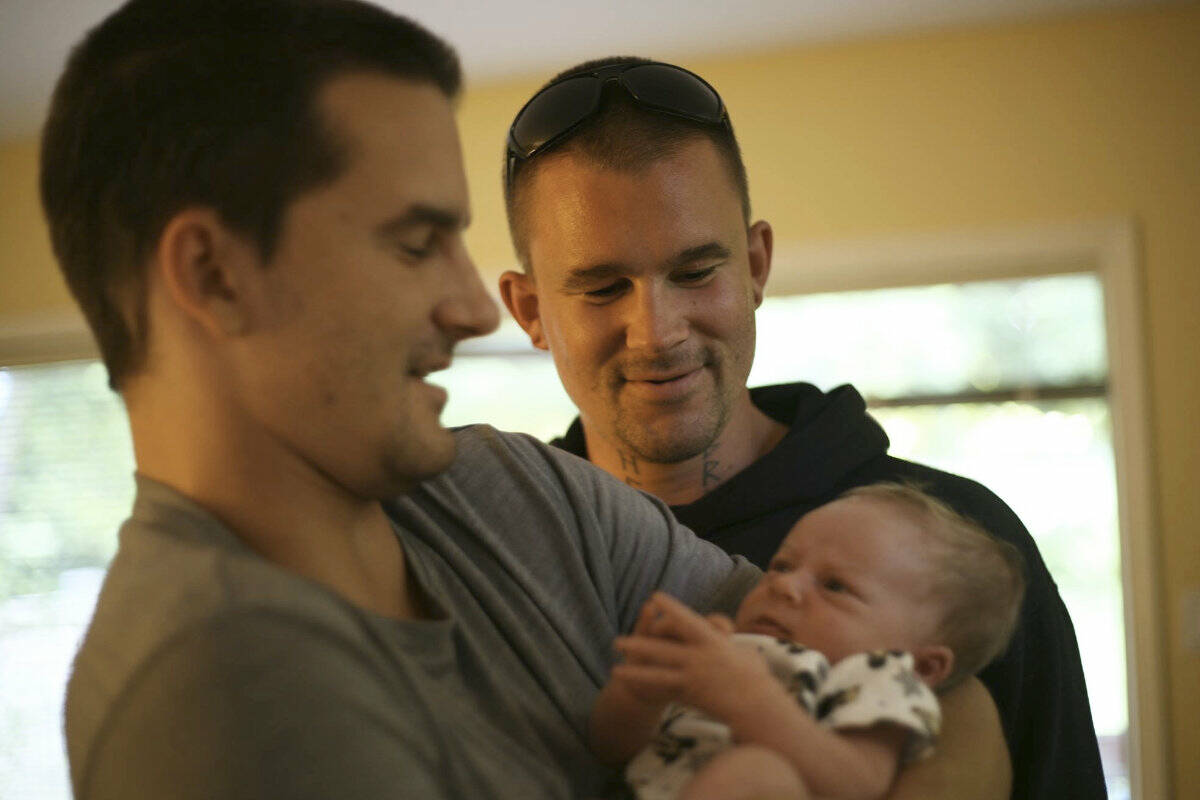

Michael had his first son at age 21, which prompted him to get sober. He worked as a carpenter, and after his marriage collapsed he started another relationship that begat another boy. But that partnership also ended, and not long after Michael relapsed.

He lived in various West Kootenay communities for 14 years, with stops in Rossland, Pass Creek, and Salmo. It was in Nakusp he had access to the provincial safe supply program that provides pharmaceutical opioids as clean alternatives to street drugs.

But gaining access to his prescription was not always worth the effort for Michael.

Walking to the pharmacy and making appointments on time was difficult for him, and if he missed a date he would resort to illicit drugs that provided a better high. They were also easier to take than Suboxone, an opioid agonist therapy he’d been prescribed as a safe alternative but came with its own side effects.

One of the program’s requirements meant Michael had to commute to Nelson by bus for regular urine testing. If he missed an appointment with the Nakusp pharmacy, Stefan said Michael would have to go to Nelson again for an in-person meeting to restart his prescription.

In late 2020, Michael underwent a 10-day detox at Castlegar’s Axis Family Resources. The next step for patients is typically a six-week stay at Bridgeway Recovery and Addictions Services, an intensive treatment program in Kelowna, for which a referral is required.

After that, people 19 and older can return to the West Kootenay and enter the eight-bed Kootenay Boundary Adult Supported Recovery Program, which focuses on life skills training but requires completion of an intensive treatment program like the one in Kelowna.

But Michael didn’t do more than the detox. It isn’t clear why, but Stefan says there was nothing prepared for him when he left Castlegar.

“He literally just walked out onto the street, and there was no housing, there was no recovery area, there was no one to even meet you to say, ‘Hi, you just completed detox. What do you need?’ You literally just stepped out and no money, wrong day for the bus, and you’re left sitting there, a raw, beaten-up piece of human.”

The choice he made

Michael’s health declined after he moved to Nelson’s streets in 2021.

He broke his collarbone after falling off a bike. He was beat up and robbed repeatedly — shoes, clothes, phones, a bank card and ID, all taken from him on multiple occasions. And his addiction became worse.

Stefan says Michael used to wake in the middle of the night and stand in front of the Hub for hours because he worried he might miss Nelson Street Outreach taking him to an appointment.

But he also craved human connection, even a small acknowledgement that he existed. He found that at the Hub, where he could socialize with other people.

“We take it for granted, but a tiny little interaction is the entire basis of their entire day,” says Stefan. “They’re literally walking, thinking, ‘I saw someone, I said hi, they recognized me, what a great day.’ We don’t really appreciate that that’s the level of of interaction and function that they’re dealing with.”

After Judith’s visit in July of 2022, it was obvious to the family that Michael needed an intervention. Stefan decided he would bring Michael back to Vancouver with him, but when he picked Michael up in August of that year he found his brother struggling to walk or even talk.

For the next eight months, Stefan made daily trips with Michael to a rapid access addiction clinic in Vancouver. Within a couple weeks Stefan saw his brother was improving and even contributing a little to the household.

Michael, Stefan says now, wanted to recover.

But as he made progress, Michael grew lonely. Stefan had to work, which meant Michael was usually left on his own during the day. He missed a girlfriend he had in the Kootenays, as well as friends in Nelson. Without drugs or the constant search for drugs, Judith says Michael lost purpose in his life.

“The worst part of removing the searching for drugs every day for people is that when that goes without some other supports, you have tons of time now but you have no interests. You have no way to to make the day productive.”

Two months before his death, Michael returned to Nelson, in April 2023.

He lived outdoors, began using street drugs again and soon developed a viral pneumonia that was likely exacerbated by his opiates, which can suppress the respiratory system. That led to multiple stays at hospitals in Nelson and Trail, and regular meetings with nurses at the Hub.

During this time, food programs and other social services in Nelson were facing funding cuts.

Judith addressed a letter to city council about this on June 27, 2023. In it, she wrote about how her son had “become invisible as a citizen of Nelson.”

Michael was found dead of a drug poisoning the next day.

When an officer arrived at her home in Nanaimo to break the news, Judith didn’t cry. It was news she had already spent decades preparing to hear.

Something less than a person

Nelson has become a difficult place to remain and stay alive in for anyone with a substance-use disorder.

Since the Hub closed in March, a camp has been set up outside Nelson City Hall by unhoused residents protesting its closure and calling for more supportive housing.

BC Housing has since told the Nelson Star that the North Shore Inn, which it purchased in 2022 to provide subsidized housing and supports for street-entrenched individuals, has been mostly empty since last fall.

Only seven people are currently housed at the site’s 30 units, due to what the province says are required water and electrical renovations, but that work has yet to begin and BC Housing said it couldn’t provide a timeline for completion.

On April 15, the Ministry of Addictions and Mental Health announced it was funding 240 new complex-care housing units for people living with mental health, trauma and addiction issues. None of the units will be located in the Kootenays.

Nelson still has no supervised site to smoke drugs, despite inhalation being the most common mode of consumption among people who die of drug poisoning in the province, according to the BC Coroners Service.

Interior Health had planned on a site at its Nelson Friendship Outreach Clubhouse, but public backlash in May 2023 forced it to scrap the idea.

Over 14,000 people have died in B.C. due to toxic drugs since April 2016. Nelson, meanwhile, set a new annual record of 16 drug poisoning deaths in 2023.

One of those 16 people was Michael Guy.

Judith and Stefan believe Michael might be alive today if he didn’t live in rural B.C.; there are too many barriers and too few treatment options.

The tragedy, they say, is that Michael was a son, a brother, a father. But because he suffered from an addiction in B.C., Judith says her child was treated as something less than a person.

“Michael had a very strong sense of personal integrity and, unfortunately the way he lived, the rest of society never got to see that.”

In Nelson, a safe injection site and drug checking service is available at ANKORS, located at 101 Baker St. Stepping Stones emergency shelter at 816 Vernon St. can house 17 people for stays of up to 30 days.

READ MORE:

• Nelson diner owners say demand has increased for free meal program

• Canada’s opioid deaths double in 2 years, men in their 20s, 30s hit hardest

• B.C.’s nurses support harm reduction, but call for additional safety measures