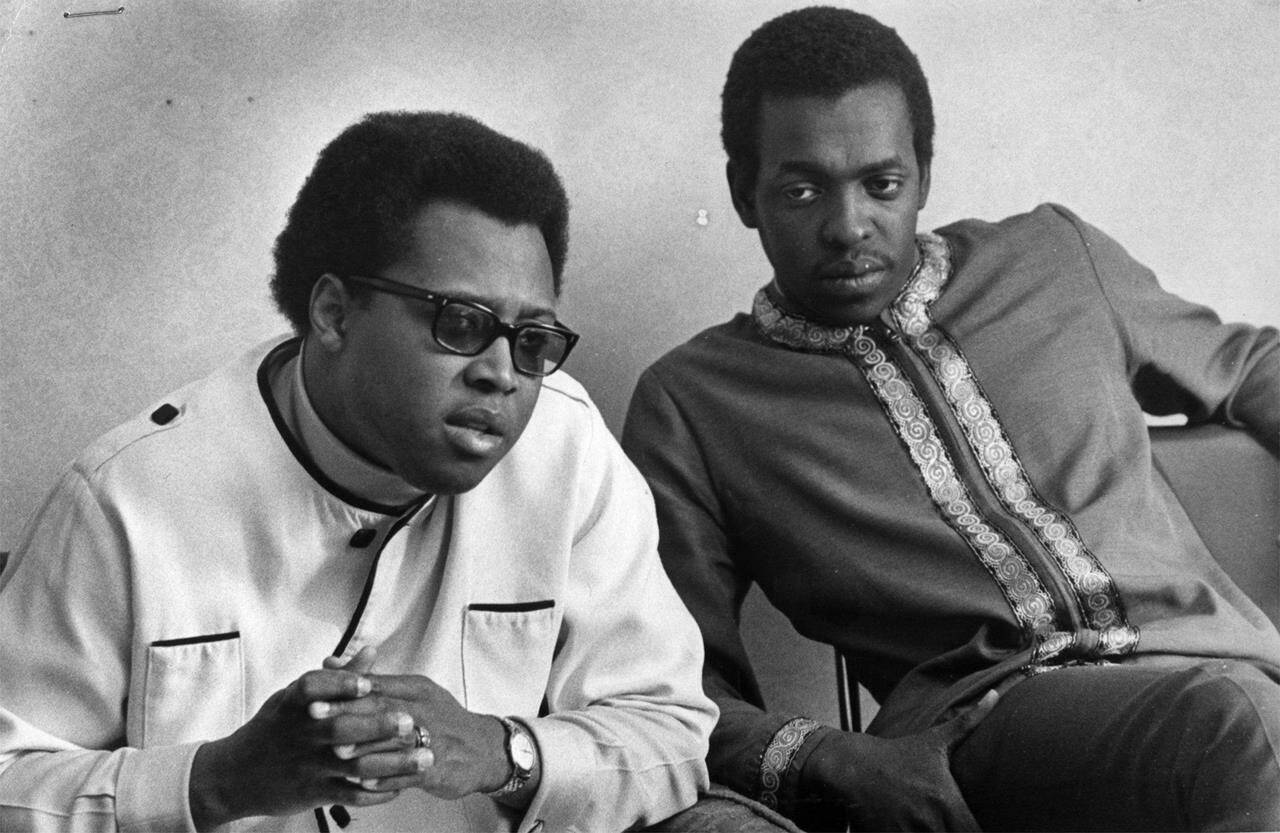

It has long been known that the RCMP Security Service took a keen interest in Roosevelt “Rosie” Douglas, a Black rights activist who attended school in Canada and would go on to be prime minister of Dominica.

But recently released records reveal just how far the Mounties would go in the early 1970s to keep an eye on the young visitor from the Caribbean.

Douglas, the son of a wealthy coconut grower in tiny Dominica, came to Ontario to study agriculture before moving on to Sir George Williams University in Montreal.

Initially a supporter of the federal Conservatives, he became an outspoken advocate for the advancement of Black people and forged ties with international movement leaders.

Though he was a master’s student at McGill University by early 1969, Douglas emerged as one of the leaders of a protest at Sir George Williams against alleged racism. As police moved to evict the student demonstrators from the university’s computer centre, a fire broke out and chaos ensued.

Douglas was among the dozens arrested and charged. He served 18 months in jail and was forced to leave Canada in 1976 after fighting to stay.

Douglas promoted the push for Dominica’s full independence from Britain and would lead the country as prime minister for a short time before his death in 2000 at age 58.

A commission of inquiry into questionable RCMP security activities publicly confirmed more than 40 years ago that Douglas was a target of Security Service surveillance while in Canada. The Mounties recruited an informant who infiltrated the Black activist community and became an associate of Douglas.

A special operations group at the Security Service developed a national program of disruptive countermeasures in the early 1970s to prevent or contain what the force saw as the potential for political violence by agitators of various stripes.

Specific targets of the program, which came to be known as Checkmate, were classified for many years. But records disclosed through the Access to Information Act reveal that one of these actions was aimed at eavesdropping on Douglas’s conversation with a fellow activist.

The RCMP knew Douglas used his own car to travel short distances but unwittingly depended on one of the force’s informants to transport him on longer trips.

Douglas was heading to Toronto to meet an important contact visiting Canada from the Caribbean. The RCMP reasoned that if his car were immobilized, Douglas would need to travel in the informant’s vehicle with the visitor, allowing “us to monitor their discussions through technical means,” says an internal account of the Checkmate program, released under the access law.

“A chemical, harmless to the engine, was introduced to the gas tank of Douglas’ car for this purpose. The operation was unsuccessful due to the chemical’s malfunction.”

However, another effort saw the RCMP “conduct an operation to discredit Douglas as a leader within the Black community and factionalize an already shaky alliance of Black groups Douglas was attempting to bring under his control.”

The RCMP adopted the proactive Checkmate tactics out of concern that existing legal mechanisms were either reactive and therefore inappropriate to intelligence needs, or inadequate to deal with new security threats.

The RCMP archival records highlight concerns about the emergence in the 1960s of more radical elements of the New Left and the extreme right. They point to expanding membership in Communist, Trotskyist, Maoist and other political organizations, including the separatist FLQ in Quebec.

The Mounties were also worried about “Canadian extremists” making links with foreign groups such as the Irish Republican Army, Palestinian organizations, and the Black Panther Party and Weathermen in the U.S., “all with a bloodied record of politically motivated violence and assassination.”

In the early 1970s, such Canadian elements were not united under a single banner, the RCMP wrote. “Individually, their actions seemed to be manageable, but the prospects of a Common Front foretold alarming consequences for civil order.”

It is one thing for authorities to take action against individuals who are directly advocating violence, but quite another to silence people who are simply espousing radical views on the basis they might take up weapons in the future, said Steve Hewitt, whose book “Spying 101” examined RCMP surveillance of university campuses.

“That strikes me as rather dangerous in a free society.”

Researcher Andrea Conte, who has also delved into police operations against activists during the period, doesn’t feel he has a complete picture of the RCMP activities with regard to Douglas. Conte points out that Douglas unsuccessfully appealed to appear at the inquiry into the RCMP in the late 1970s.

In a letter outlining why he should be allowed to testify, Douglas wrote he had been part of an open and democratic struggle against racial injustice that was attracting support from parliamentarians, churches and other prominent organizations.

“What did the RCMP fear in me — a non-violent civil libertarian?”

Security Service tactics during the era included illegal break-ins, the theft of a Parti Québécois membership list and the burning of a barn to prevent a meeting from taking place.

The RCMP’s deeds led to the disbandment of the Security Service and the 1984 creation of the civilian Canadian Security Intelligence Service.

Eight years ago, CSIS received authority to go beyond traditional intelligence gathering and engage in threat reduction measures against targets — legalization of the kind of “dirty tricks” that got the RCMP in trouble.

In theory, there is more awareness of these techniques and restrictions in place today, but lingering tensions over allowing a domestic intelligence agency to carry out disruption operations, said Hewitt, a senior lecturer in American and Canadian studies at the University of Birmingham in England.

“There’s always the potential for it to be abused.”

Jim Bronskill, The Canadian Press