Residents of northwestern B.C. are praising Space X technology, stating Starlink internet is revolutionizing digital connectivity for northern communities.

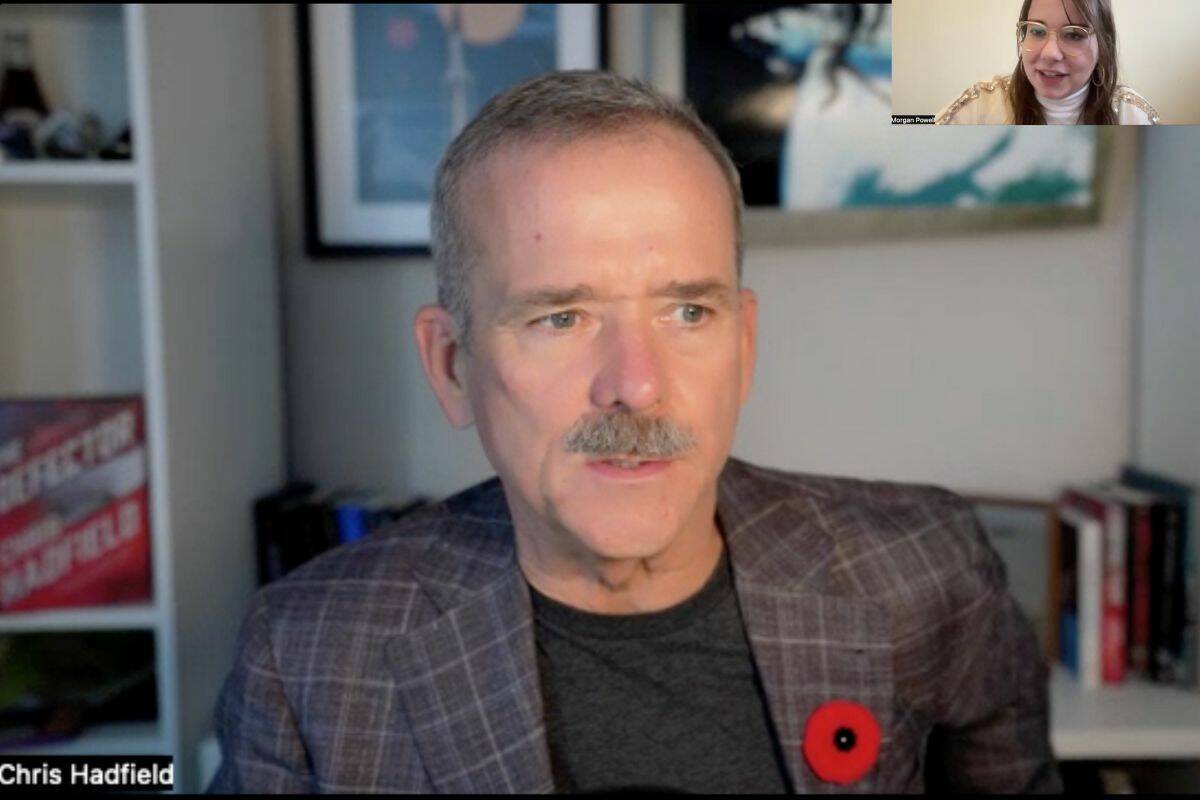

Chris Hadfield, former NASA director of operations and an International Space Station commander, took some time to chat about rural internet connectivity in Smithers, and how connectivity is influenced by satellite technology.

“Access to the internet is very much the difference between education, health care, and jobs,” explained Hadfield. “For Canadian financial viability, it’s really important that 99 per cent of Canadians have some sort of internet connectivity.”

“I regularly consult with Canadian media to help them understand what’s going on,” said Hadfield, who just released a fiction book The Defector, inspired by his time as a fighter pilot with the Royal Canadian Air Force.

The retired astronaut is devoting his time to initiatives designed to help citizens better understand how air and space technology operates, including internet broadband systems.

By 2030, all Canadians will have access to high-speed internet at 50/10 Mbps, according to the federal government. This is a target date, outlined by the UN’s Global Sustainability Goals, as part of a broader conversation that discusses internet access as a basic human right.

The target date is even sooner for B.C. residents, according to the provincial government. All B.C. communities, including rural and Indigenous households, will have access to internet by 2027, according to the province.

“74.2 per cent of households in rural B.C. and 77.2 per cent of First Nation households on reserves have access to the recommended internet speeds, leaving the remainder underserved,” said the provincial government.

The Connecting Communities B.C. program, announced last year, is providing $830 million to bring internet to underserved communities.

“We’re committing to accelerate the target in our province to close the digital divide and connect all of B.C. by 2027,” explained B.C.’s minister of Citizens Services Lisa Beare. “We know how important connectivity is to every British Columbian to support our growing economy and ensure we are putting people first.”

The central areas of Smithers — Main Street and the remainder of the downtown core — are serviced through fixed wireless internet.

However, as a part of the Universal Broadband Fund (UBF) program, Smithers has received funding to operate CityWest through a fibre-optic cable network. Telus’ fibre-optic cable network was also a funding recipient through the Rapid Response Stream (RRS) program. Many of the more rural areas in Smithers, that do have access to internet, are serviced this way.

In order for internet to be received through fibre-optic cables, they need to be wired somewhere, either a tower or a distribution centre. This can become complicated in rural areas, Hadfield explained.

“If they can stick a tower up in the middle of Smithers, and that tower is connected to a fibre optic source from somewhere, then everybody just needs to get a little 5G receiver.”

But in an area such as rural Smithers, where houses can have acres of space between them, servicing the entire community this way can become complicated.

“They have to dig a trench and they have to actually run a little glass tube,” Hadfield said. “And so naturally, they’re going to follow wherever there’s already a [well-developed] road.”

Hans Parmar, media relations spokesperson for the Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED), explained that the federal UBF and RRS fibre-optic cable projects are intended to be a “backbone” for connectivity. But 2027 is still years away, and with a digital landscape in a constant state of flux, rural residents are looking for alternative ways to stay connected. Many Smithers residents have turned to satellite technology to mend the virtual gaps.

Thanks to satellite internet, Smithers resident Nikki Papps is able to complete her university degree online.

“We live 500 metres off of Highway 16,” explained Papps. “For years we struggled with paying for satellite, house phone, cell phones and Telus internet services via a hub set-up.”

“Starlink put their equipment on sale and we took the plunge and switched over. This was several months ago, and we love it.”

Starlink is an American company, owned by SpaceX. Several Canadian companies, such as Kepler and Xplore, are off to a successful start launching similar technology. However, they don’t have the funding to operate in the same capacity that Starlink does.

“The only company that is actually doing it right now is Starlink, which is part of SpaceX,” said Hadfield.

Starlink’s funding model is different than what is typically offered by Canadian internet providers, as residential users are not required to sign a contract.

“They started launching things for-profit in space… over a dozen years ago, and then they started having reusable rockets about eight years ago,” explained Hadfield. “And now they have the cheapest, and by far and away, most reliable rocket service in the world.”

Launching rockets into space will cost “hundreds of millions of dollars,” so it can be difficult to acquire a loan to cover start-up costs, said Hadfield, who spoke positively of the work his Canadian colleagues are accomplishing.

Currently, Canadian satellite companies are focused on contracts with government and commercial clients, as it is more financially viable than servicing residential users.

“[Starlink] launched like, you know, 50 [satellites] at a time, so it’s given them a tremendous first mover advantage, because they didn’t have to buy launches,” explained Hadfield.

SpaceX is owned by Elon Musk, who is currently estimated to be the wealthiest person in the world, with a net worth of $USD247.3 billion. Over the years, Space X has received several billion dollars worth of funding from the U.S. government, as well as support from NASA technology and staff.

“I think it’s really important for Canada, that we have allowed Starlink in and I talked to the people in the government back when Starlink was trying to come into Canada, and had discussions back and forth,” Hadfield said. “And I was, like, well, we could wait for Telus lightspeed, or we could wait for all of the major service providers to lay their cable to the remote locations, and then put up towers and everything.

“But what we’re really doing is sort of denying 30 per cent of Canadians a whole bunch of opportunity in life for for a whole bunch of years. And that’s not really serving Canada very well, at least not in the short term. So I think it’s smart to be doing both.”

Because Space X launched their satellites into the polar orbit, the Starlink constellation can travel from the north pole to the south pole, servicing Smithers and other rural communities in the north. This includes industry camp workers, who can purchase a package that costs between $329 and $6,390 a month.

“Drive 50 miles east out of Smithers or whatever northern town you are in, and you just stick your little antenna outside and just use the power from your battery,” explained Hadfield.

The basic plan for Starlink residential users is currently $140 a month, with priority customers paying upwards of $635 a month. Equipment fees are typically a one-time fee of $759, with sale prices fluctuating regularly. Conditions and fees are subject to change, as Starlink users are not expected to sign a contract.

READ MORE: SpaceX’s Starlink internet active on all 7 continents

READ MORE: Astronaut Chris Hadfield working with King Charles on ‘Astra Carta’