By Zak Vescera, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

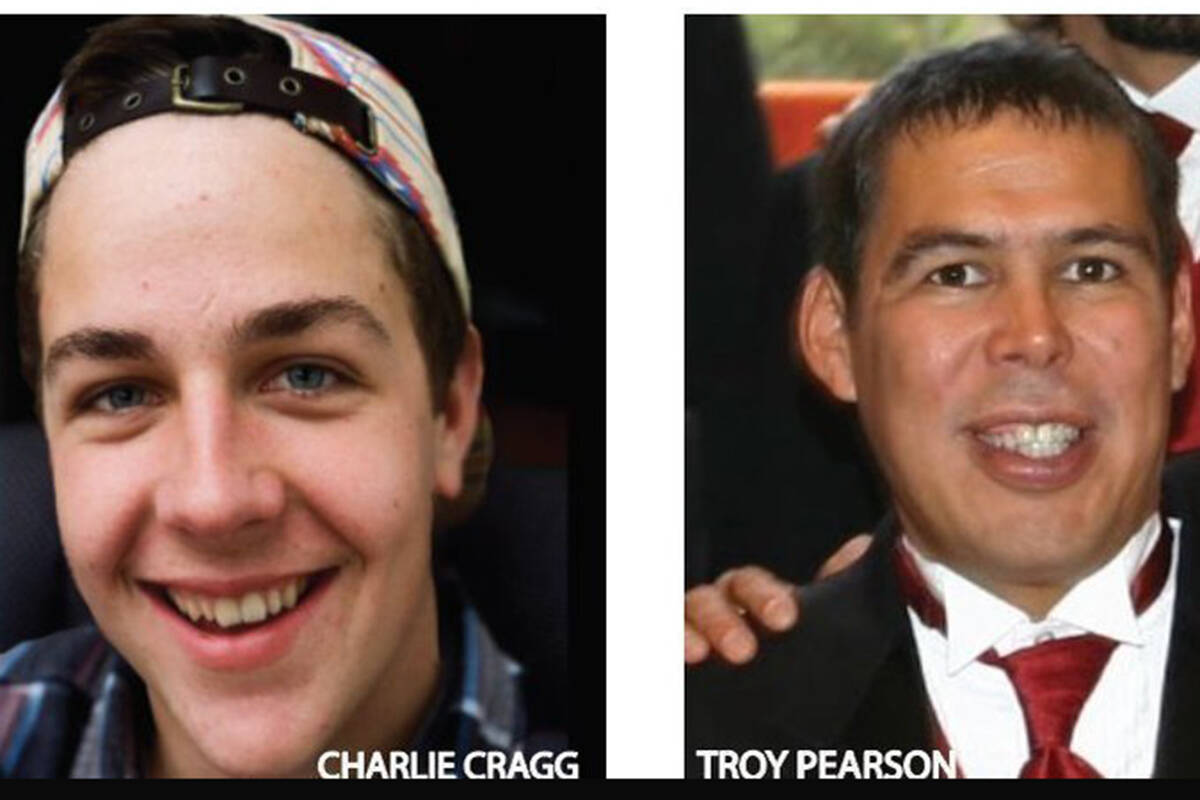

Troy Pearson had never wanted a job on land. On Feb. 10, 2021, he got up early to make a big breakfast for his wife, Judy Carlick-Pearson, and their 11-year-old son who had an 8 a.m. hockey practice in Prince Rupert.

Pearson worked on tugboats at Wainwright Marine, a tug and barge company in nearby Kitimat. He had been on the water since he was a 10-year-old on his dad’s fishing boat, but Carlick-Pearson said safety problems at work were keeping him up at night. “He didn’t feel safe,” she said.

The two had big plans to open an auto detail shop together the next month. Carlick-Pearson still remembers the smell of him frying bacon, the coffee they shared together, the ride she gave Troy to work, the kiss goodbye and the supportive honk she gave him as he walked away.

It was Charley Cragg’s first day on the job. The 25-year-old had just moved to nearby Terrace and got the job at Wainwright while waiting in the hiring pool for the coast guard. Cragg, too, had loved working on water; his mom Genevieve Cragg said he was a fishing guide and worked in conservation before his first day at Wainwright, a day she plays in her head every month. “On the 10th of every month at noon, I tell Charley not to get on that boat,” Genevieve Cragg said.

But he did, and so did Pearson. The MV Ingenika set out late, hauling a barge more than five times its length filled with construction equipment bound for a nearby mine. Environment Canada had warned of a storm; gale-force winds of up to 50 knots and freezing cold spray, but Ingenika set sail anyway.

On Feb. 11, after midnight, the tug sent out an emergency beacon. Then it vanished.

Ingenika sank to the bottom of the Gardner Canal, its barge found floating nearby. Cragg and Pearson were lost at sea. A third crewmate, Zac Dolan, was rescued after swimming ashore.

“You’re never the same person,” Genevieve Cragg said on Wednesday. “There’s nothing to get over. You change, you absorb, but you never get over it.”

On Monday, B.C. Crown prosecutors laid eight charges against Wainwright and its director, James Geoffrey Bates, alleging the company violated the Workers Compensation Act by failing to protect its workers, or provide basic training or life-saving equipment.

READ ALSO: Tug company, senior official charged in fatal 2021 sinking off northwest B.C. coast

Transport Canada had already fined Wainwright and another company owned by Bates $62,000 for violations linked to the sinking.

Graeme Hopper, a lawyer for Bates and Wainwright, said his clients were reviewing the charges and would not comment further at this time.

Carlick-Pearson and Cragg say the charges don’t go far enough. They want immediate reform in B.C.’s tugboat industry, where businesses and unions alike say lax regulation and poor oversight create safety risks. And they want stiffer punishment for companies that endanger workers in a country where businesses almost never face criminal charges.

“Some people think situations like this could be celebratory,” Carlick-Pearson said, speaking about the new charges. “But really, it’s like a punch in the stomach.”

“It’s grotesque to think that someone’s life is valued so little in Canada.”

The Ingenika was more than half a century old when she set sail for Kemano that night. Federal shipping records show the tugboat was first registered in 1968 and was built at a shipyard in New Westminster.

The boat had an official gross weight of 14.63 tonnes, just below the threshold for mandatory federal inspections. Transport Canada inspects tugboats 15 tonnes and up every year. But the inspection regime for smaller vessels is optional, and very few boats take part.

“Because of their tonnage, they don’t bear any scrutiny,” said Jason Woods. Woods is the president of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union Local 400. According to Transport Canada, only 84 of the approximately 1,300 small tugs in the country were registered in the voluntary compliance program as of Feb. 1. Those boats also aren’t measured to see if they are still under 15 tonnes, Woods said.

“It’s a voluntary compliance program, so people are voluntarily ignoring it,” Woods said.

More than 80 per cent of those small tugboats are in British Columbia. Decades ago, says Paul Hilder, president of the Council of Marine Carriers, those vessels were used to haul goods up and down sheltered waterways like the Fraser River, or to tow logs. But as the forestry industry declined, some operators began using those vessels in the open sea. There’s no limit on how long or heavy a barge the boats can pull.

“The difference is that regionally, out here, we just have a problem with a smaller number of 15-tonne tugs that are probably being repurposed from what they were intended to do and are being operated outside parameters that were originally expected for them,” said Hilder, whose organization represents the tugboat industry.

Hilder says that creates a two-tiered system. Bigger tugboat owners have to undergo annual inspections and abide by federal codes; smaller tugboat owners don’t have to, making their operations cheaper. In some cases, Hilder says, those operators may not even know about safety standards because there is no inspection system.

“The barrier to entry is basically buying a boat,” Hilder said.

Canada’s Transportation Safety Board has recorded 298 accidents involving barges or tugboats from 2011 to 2021 in the Pacific region alone. That breakdown doesn’t say how many were small tugboats, but industry experts and unions alike believe those boats can be particularly dangerous when operated incorrectly.

A 2021 study from the Ocean, Coastal and River Engineering Research Centre, for example, noted that some larger companies worried that existing regulations “may be compromising safety of operations of small tugboat operators.”

The Transportation Safety Board has argued for years that all boats should be part of that inspection regime. Hilder agrees. He believes that hasn’t happened because Transport Canada doesn’t have the resources to do it. “When you look at the sheer numbers on them, putting an inspection regime on them that is going to cover every facet of the 15-tonne tugs is a daunting task,” Hilder said. As it stands, he said, many in the industry say Transport Canada rarely inspects vessels in northern B.C.

“Traditionally, in the industry if you’re north of Campbell River you will rarely see any kind of inspection regime,” Hilder said.

Transport Canada says it currently has 340 marine safety inspectors across the country, though roughly only 20 per cent of them are conducting inspections on small vessels. Woods believes that is far too few to fulfil the mandate Transport Canada currently has, let alone expand it.

“Even if you had all inspectors inspecting tugboats, it would take you years to comb through it,” Woods said.

Taylor Bachrach, the MP for Skeena-Bulkley Valley, which includes Kitimat, has been pressing for two years for new regulations in the tugboat industry. He says he’s not satisfied with the government’s response.

“My concern is that the federal government is moving towards a safety management system approach for these smaller vessels. And what we’ve seen in other sectors, such as the rail sector, is that safety management systems are a kind of self-regulation where the companies write their own rules,” Bachrach said.

Bachrach also wants tougher penalties for companies found responsible when a worker is killed on the job.

Wainwright and Bates, who also owns a marine transport company with locations in Vancouver and Horseshoe Bay, have not been convicted of the eight regulatory charges laid against them this week. But if they are, the maximum fine for a first conviction is less than $778,000, and the maximum jail sentence is six months.

“We were disappointed there wasn’t a criminal charge against causing death, against Wainwright and James Bates. That was our original plea,” Carlick-Pearson said.

In Canada, companies can face criminal charges for negligence causing death following changes that came into effect after the Westray Bill was passed, legislation named after the deadly Nova Scotia mining disaster that killed 26 people.

But since it came into law in 2004, only a short list of people have been convicted. As of 2022, only one person had served jail time, with one other person serving a community sentence.

“The number one thing is that it’s hard,” said Jennifer Quaid, a law professor at the University of Ottawa. “And the reason it’s hard is that the criminal law system we have in Canada was deigned to apply to individuals.”

Proving criminal negligence, Quaid said, means proving a “marked departure” from what a reasonable person would do. In a normal criminal trial with an individual, that’s difficult. When it concerns an organization, she said, establishing negligence is even harder. “The practical reality is that the employer will typically be motivated to try and come and deal with prosecutors,” Quaid said.

Genevieve Cragg says the eight charges against Wainwright and Bates are significant. But she too is waiting to see if RCMP recommend criminal proceedings. She says Charley wasn’t trained in the yard before he went out on the water, something she says is a clear safety violation.

“I really want the message to go out that without criminal charges, we’re sending a message that bad behaviour is rewarded,” Cragg said.

Cragg and Carlick-Pearson have spoken to media dozens of times since the Ingenika sank. Both have willingly spoken to reporters and government officials about what they describe as the worst moment of their lives.

Cragg wants to see specific changes in law linked to Ingenika’s sinking. “I am the biggest stakeholder in this,” she said. “That was my son, and he was taken out.”

Carlick-Pearson is motivated by her son. “My son is just like his dad in a sense that he has saltwater in his veins,” she said.

“If my son ever wanted to be in a company that was lacking in safety and regulatory practices, that could put him at risk.”