Members of an advocacy group for drug users have gathered to celebrate the start of decriminalization in British Columbia and discuss how they will “fight back” against any efforts to seize illicit substances that meet the 2.5-gram threshold allowed under the first such policy in Canada.

The meeting at the office of the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VANDU) on the first day of the new policy began with a man handing out “know your rights” cards.

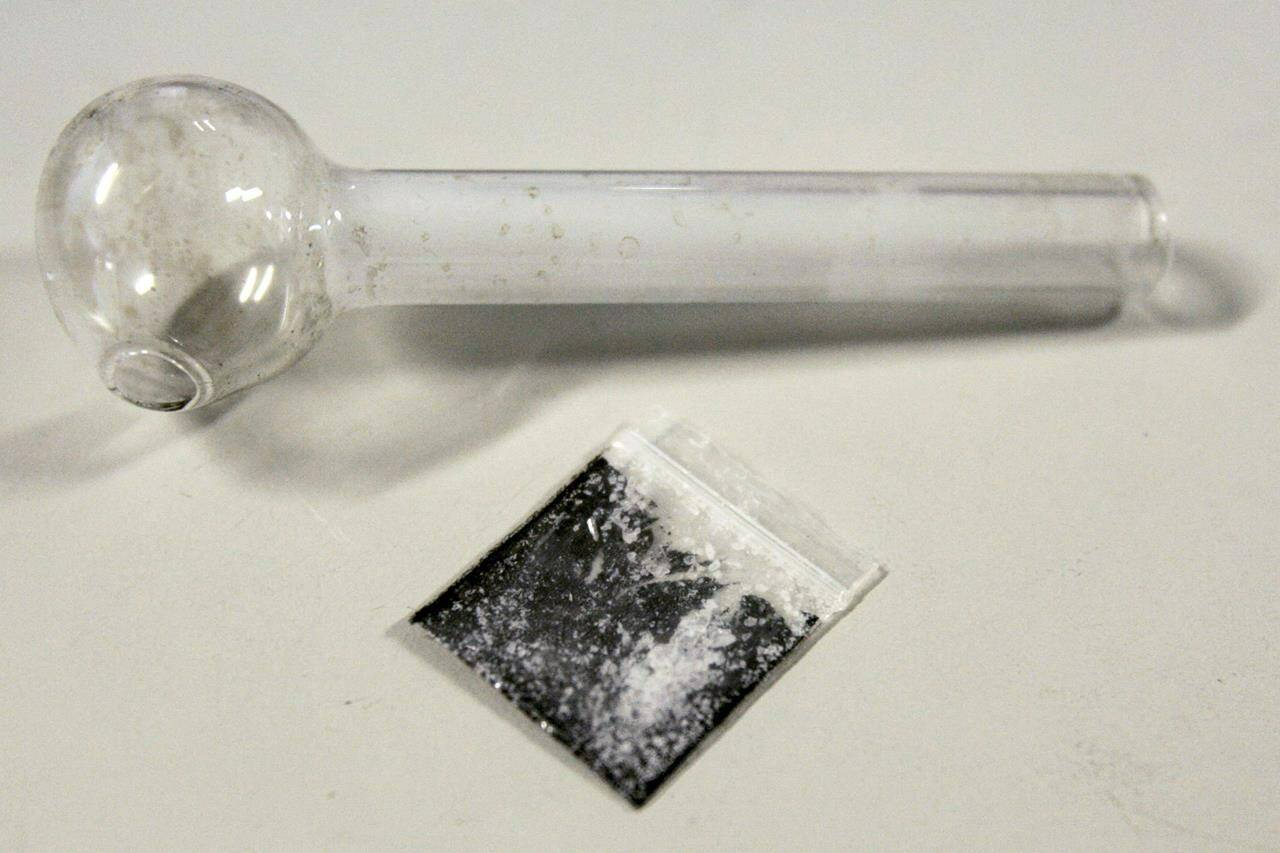

They say people aged 18 and over carrying up to 2.5 grams of opioids, cocaine, methamphetamine and MDMA, or ecstasy, for their own use will not have those drugs confiscated. There’s also a list of reasons why someone would not be protected, including possessing any amount of any other substance, trafficking or selling drugs.

Decriminalization began in B.C. on Tuesday after the federal government granted the province’s request for an exemption from the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act as part of a plan to combat an overdose crisis that has claimed over 11,000 lives there since 2016. The pilot project is slated to continue for three years.

People who carry the permitted amount of drugs will not be arrested or charged, and police can no longer seize their substances. The B.C. government says the aim of decriminalization is to reduce stigma so people struggling with addiction are more likely to reach out for help.

Vincent Tao, a community organizer with VANDU, told about 30 people packed into a room that the pilot is “just a foot in the door” for the group, which has been advocating for decriminalization for its entire 25-year history.

It was also involved in a legal battle against the former Conservative government to keep open Insite, North America’s first supervised consumption site, and celebrated that victory following a Supreme Court of Canada ruling in 2011.

“The fight continues,” Tao told the gathering of former and current drug users.

“But ultimately, the power and the discretion still lies in the hands of the cops. So, we’ve got to keep an eye on these things. Report back, right to this room,” he said of the group’s efforts to compile a database of people’s experiences.

“We will, with the support of our partners, friends and allies, keep track of this experiment in our lives for the next three years.”

Members of VANDU, who were at the “core planning table” of meetings on decriminalization for about a year with others including Moms Stop the Harm, police and the B.C. government, suggested 18 grams as a threshold.

The B.C. government applied for 4.5 grams, but as a cumulative amount for all the permitted drugs, while police wanted a total of one gram.

Tao called for drug users to be “armed” with their rights cards during any police interactions, noting officers will not be carrying scales and only “eyeballing” substances they believe could be over the threshold.

Fiona Wilson, vice-president of the British Columbia Association of Chiefs of Police, which represents 9,200 members, said Monday that the province’s death toll from illicit, toxic drugs, many cut with the opioid fentanyl, is double the national average.

“Destigmatization is a significant step toward making our drug policies more progressive. And it recognizes that substance use is a health and not a police matter. Police can now focus on those doing the most harm in this crisis — persons and organized crime groups who import, manufacture and distribute these toxic substances.”

Mental Health and Addictions Minister Jennifer Whiteside has said the province is working toward providing more treatment and harm-reduction services after expanding programs to offer a safer supply of alternative drugs.

Caitlin Shane, a staff lawyer with the Pivot Legal Society, which has also called for a higher threshold, told those assembled at VANDU she was concerned that a benchmark for evaluating the success of decriminalization may be a marked reduction in overdose deaths. Shane also worried about the need for adequate supports for those who need them.

Ottawa and B.C. are still trying to work out which indicators will be used to evaluate the policy, but publicly available data are expected to be updated online every three months.

“We can’t measure the success of (decriminalization) by lives being saved or not because the fact is that decriminalization today does not mean that we can walk out tomorrow and have access to a regulated drug supply. It does nothing for the drug supply,” Shane said.

“So, we need to be clear that what we’re measuring here is incarceration rates, cops in people’s lives, reducing stigma.”

Garth Mullins, a board member of VANDU, has criticized both levels of government for relying on police to hand out information cards that would refer people who use drugs to voluntary health services.

Mullins told the group that a measure of decriminalization’s success would be less police intervention.

“We gotta fight for how this thing is measured. Luckily, we’ve had 25 years of fighting,” he says of VANDU’s efforts to open Insite, which received a federal exemption in 2003. The facility, which is about six blocks away in the Downtown Eastside, allows people to shoot up their own drugs under medical supervision.

Members of VANDU were also instrumental in opening unsanctioned overdose prevention sites before the B.C. government allowed them to operate as the death toll from toxic drugs rose, forcing the province to declare a public health emergency in 2016.

Now, Mullins says he’s concerned about Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre’s stance against decriminalization. He reminded the group that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau also vowed not to introduce the policy before reversing course last May with an approval of B.C.’s application.

After celebrating the start of decriminalization, members of VANDU bowed their heads in a moment of silence to remember those who have fatally overdosed and to acknowledge the latest grim statistics released hours earlier by the B.C. Coroners Service. They showed 2,272 people died last year, the second-highest annual number after the previous year, when 34 more people lost their lives.

Eris Nyx, co-founder the Drug User Liberation Front (DULF), told the gathering she would continue her tradition of handing out free, tested heroin, cocaine and methamphetamine as she does every time the overdose numbers are updated.

Tuesday marked the 13th “Dope on Arrival” giveaway, Nyx said as people walked up to a table one by one to claim a package of drugs when their name was called.

“We are taking these drugs as a way to prove the community can control its own safer supply,” she said.

“Here’s the real tragedy. If we don’t regulate the drug supply, people will die. And I’m telling you, do not use alone, especially if you’re an opioid user.”

The group has continued selling drugs, bought on the dark web, through a compassion club at an undisclosed location in the Downtown Eastside despite a rejection last year of its exemption application. Health Canada has said the controlled substances were illegally bought and produced.

Nyx says DULF will file an application for a judicial review of the decision.

—Camille Bains, The Canadian Press

RELATED: B.C. MLA says illicit drug decriminalization sends wrong message

RELATED: Decriminalization of hard drugs puts B.C. in small, select group of jurisdictions