The call was loud and sustained for Quesnel mayor Ron Paull to resign.

A contingent of First Nations chiefs, residential school survivors and descendants, plus community at large repeated the resignation demand. It started at a downtown rally Apr. 2 with at least 500 people present. They marched through the streets of Quesnel to City Hall where drumming, dancing, and other expressions of protest were made, before the next meeting of city council took place. The gallery was overflowing out into the foyer and the outside parking lot.

Aware of the groundswell of discontent, Quesnel council adjusted the agenda to defer regular business to another day. Instead they held an extraordinary hearing, starting with the leaders of any governments who wanted to speak, as they represented constituencies of people.

The first two – the chiefs of Lhtako and Nazko First Nations – jointly pledged to do no further business with the City of Quesnel if mayor Paull were to be involved in the discussion.

“We can’t have a community that hands out hate literature and expects to listen to us and to take us seriously,” said chief Clifford Lebrun of the Lhtako Dene Nation, on whose land the entire community of Quesnel sits.

Paull expressed his desire to learn from the situation and to prove himself through future work.

He thanked the chiefs who spoke.

“Their words absolutely must be preserved for sharing with others on the pathway to reconciliation,” he said, when pressed by one elder to speak up on his own behalf. “I don’t intend on going anywhere. I intend on working my heart out to further the objectives of reconciliation.”

When pressed for an apology, he started by saying “I’m guilty by association,” which drew gasps and jeers from the crowd. He tried again with the words “I will express regret that all of this has happened. I am sorry it has come to this, and I will work my heart out to make reparations.”

He pointed out the next election was Oct. 17, 2026 “and I’m convinced I want to stay until that date…I am not a quitter, and I am determined in my heart to see this thing go ahead. I have apologized for the situation, and I mean that, but I’m not going to walk way.”

The outcry centred on the book Grave Error, a collection of curated essays that combine to form a theme of belittling residential school atrocities. This book was being actively distributed by Paull and his wife Pat Morton, including attempts to refer it to other elected officials, as well as School District 28.

“Our issue is with the leadership of this town,” said Lebrun. “This definitely hurts our people, and not just the survivors that have to relive it again, and wounds that have healed just a little bit from the findings of Tk̓emlúps and Williams Lake First Nation (where radar readings indicate bodies may be buried), and the other residential schools across Canada.”

He pointed to the gallery populated with elders and their descendants. Consider, Lebrun said, how important this insult must be if they were all so willing to re-live their fears and traumas just to impress upon council just how genuinely damaging those schools were, and how new damage is done by someone espousing this book but then also trying to act like a governance peer.

“To see (their generational suffering) denied and disgraced by people who just don’t believe the facts,” was unacceptable, Lebrun said. “We see only one step moving forward, and that is we will not work with this mayor, and we will not work with the City of Quesnel unless that issue is resolved. That’s unfortunate because we’ve done a lot of great works…We enjoy working with the City…We have a lot of other projects that we want to advance. But we need to know we are working with respectful people.”

Lebrun added that the jointly hosted Lhtako Quesnel BC Winter Games set an example for the entire province, but such partnerships were now in jeopardy.

“We, probably more than you guys, have a lot more reasons to hate people,” said Lebrun. “We don’t do that. That’s not a solution. Working together and building a relationship is the solution. And that is impossible to do when there is denialism and racism at the table.”

Next, council heard from chief Leah Stump of the Nazko First Nation, saying she was painfully disappointed that this topic would still have life in 2024, after the mountains of evidence of the torture these residential schools systemically perpetrated under the assumption of white superiority.

“We don’t trust very often,” she said, alluding to recently optimistic relations with the City of Quesnel. “We haven’t had a good history (of fair relations with interloping governments). And the mayor has broken the trust of all First Nations, I believe. We should not be having to prove that residential schools hurt our people. We should be working together on reconciliation and healing. While we at Nazko First Nation do not have confidence in the mayor, we hope that council will continue to commit to working with us on the partnerships we were working on together. Our community, our people, our elders, we deserve better than to have to come here to prove we were broken. We deserve better.”

Former Lhtako chief Geronimo Squinas and Lhook’uz leader June Baptiste spoke next, reaffirming the slap in the face this book represented. Esk’etemc elder Eagle Star Woman (Charlene Belleau) spoke next about how hard she and her nation were looking for the bodies of relatives who went to St. Joseph’s Mission and never came home. She felt herself to be the living counterpoint to anything written by the contributors of Grave Error.

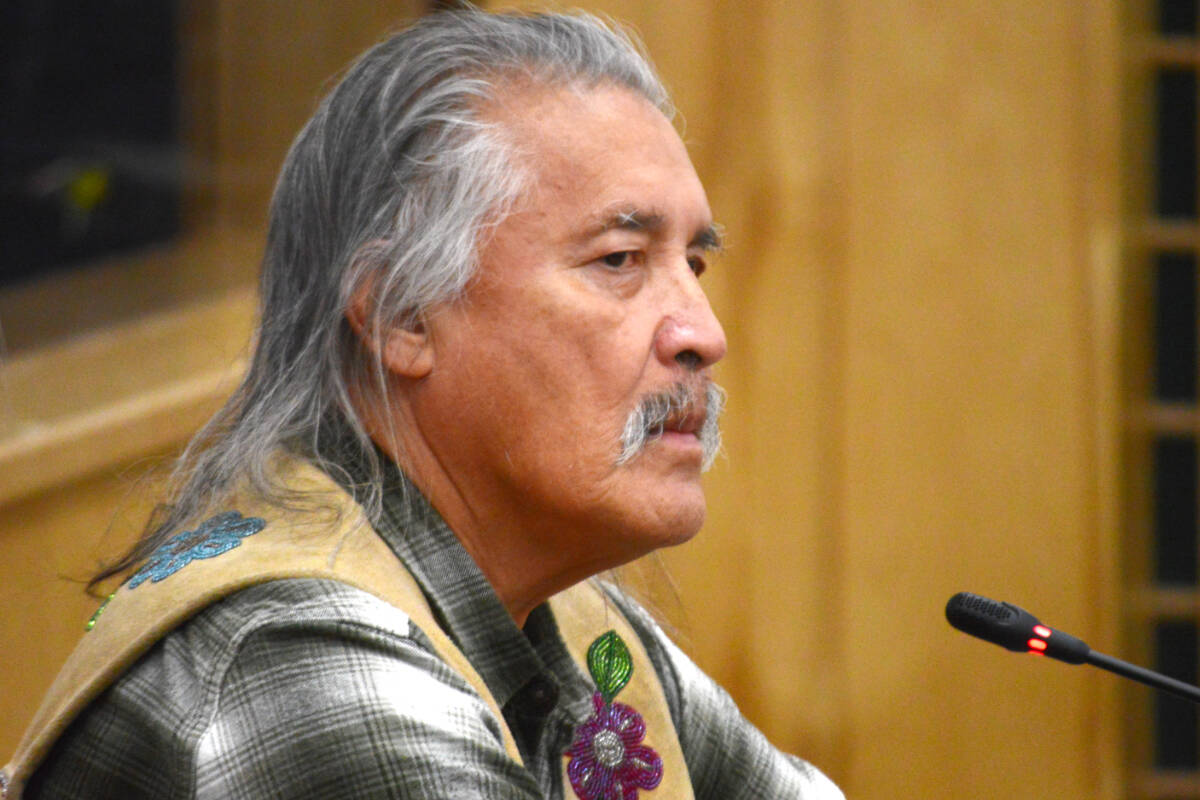

Nadleh Whut’en chief Chun’ih (Martin Louie) and councillor Roy Nooski came next to the podium from Fraser Lake, where the area’s other residential school, Lejac, once operated in the same fashion as St. Joseph’s in Williams Lake.

Nooski demonstrating how he used to inject himself with heroin. “Twenty-four years of my life on skid row to cover up the pain with alcohol and shooting up,” he said. “Not very easy to forgive” he added, saying federal prison was more kind and progressive towards him than the school.

Chun’ih fixed his gaze on Paull. “And you,” Chun’ih said, “If you knew us, what our people went through, we wouldn’t be sitting here today.”

He said he woke up one morning recently, and his daughter showed him the news of the Quesnel controversy.

“We came a long way, as people – suffered a lot as people. I thought we were just about getting to a point where we were going to start talking – a really good conversation about the resources,” said Chun’ih. “It all went away because somebody didn’t use this thing, (gesturing to head and heart together for dialogue). He reasserted his gaze on Paull and said, “If you are a man, you will just step down.”

READ MORE: Truth and reconciliation rally planned for Quesnel

READ MORE: Widdowson, contributor to the book Grave Error, coming to Quesnel

residential schoolsTruth and Reconciliation Commission