This is the third in a series of stories delving into large-scale cases of suspected fraud and how they go unresolved, and sometimes even uninvestigated, in B.C. and a few specific to Langley.

“Follow the money.”

Two men offered that advice when asked what happened to cash that vanished in one of the biggest scams in Langley history.

Brad Muller was one. He says he lost millions in business deals with Matthew Brooks, a man Muller didn’t know was under investigation for fraud when their business partnership began.

He repeatedly went to the police in B.C. to complain, but says there has been no investigation of his case.

The other was Brooks himself, who after stealing $6 million, went to prison destitute a decade later.

The fate of the missing $6 million in the Aggressive Road Building scam has never been cleared up by the courts or B.C. police. Civil court records and interviews conducted over the last several years with former business associates of Brooks reveal that millions more possibly passed through Brooks’ hands between 2008 and 2012, only to also vanish.

No one now can or will say exactly what happened to the money in a case that involved fraud, a six-year police investigation, a drive-by shooting, and accusations of Hells Angels involvement.

The Aggressive fraud

Matthew Brooks came from a family that was already prominent in the construction industry, and Aggressive Road Builders was originally founded by his father and a business partner.

“I took over when my dad went back to Imperial Paving,” Brooks told the Langley Advance Times last year. “It grew over time and for many years did very well.”

Aggressive had a full-time staff of about 60 people, and worked around the Lower Mainland, building and upgrading roads in Surrey, Langley, Abbotsford, and Burnaby.

But it unravelled and crashed into bankruptcy in 2008.

When the company’s main lender, ScotiaBank, became suspicious about Aggressive, audits discovered that the bank had extended millions of dollars in loans to Aggressive based on forged documents. Brooks and his co-accused, Kirk Roberts, would both eventually plead guilty to falsifying their own records to make it appear that municipal governments owed Aggressive significant amounts of money for paving work that was already completed.

In fact, those numbers were wildly exaggerated. At one point, Aggressive was telling their bank that they were owed $21 million for completed work, when the true amount was $3.4 million.

“I fought against it,” Brooks said. “But I was declared bankrupt, and Aggressive Roadbuilders was seized and locked up.”

The police investigation began in early 2009, but it was lengthy.

After police seized computers and files from the Aggressive offices, it wasn’t until May 1, 2012, that a forensic accounting report was completed.

During the investigation Brooks and Roberts got back into the construction business with a new firm, Blackrete, which Roberts would eventually take over, continuing to work for local municipal governments.

Charges against the two men weren’t laid until Nov. 21, 2014, and weren’t announced by the RCMP until the following year.

Legal proceedings ended for Brooks in 2017, when he pleaded guilty and was sentenced to three and a half years in prison – he has since served his sentence.

His co-accused and former employee Roberts wasn’t convicted until a guilty plea in 2019; he was sentenced to a year and a half of strict house arrest and probation. An appeal of his conviction was rejected in November 2020.

What the courts never heard was what happened to the cash. Nor did the judges ever hear about the other people who had gone into business with Brooks in the years between the start of the investigation, and the laying of charges, or the potential millions that were lost.

READ ALSO: IN OUR VIEW: RCMP must be open about their fraud-fighting efforts

Bad investments

In late 2008, Brad Muller was a Florida hotel owner and manager who was looking for new investment opportunities.

The two men recall their business partnership differently, but both Muller and Brooks agree that it started with a small web startup.

“Brad Muller and I were kind of the money behind a company that went public, that we both tried to finance,” said Brooks. “And at the end of the day, both our monies were long gone.”

Brooks said his mistake was “to tell him that I was very confident in the company, and thought it would do well.”

Muller recalls that even their first financial transaction went poorly.

“He told me he had a cash flow problem for one week,” Muller said, saying Brooks asked him to put up some money with a promise it would be paid back in a week. It didn’t happen.

“That’s when I should have walked,” Muller said now, with the benefit of hindsight.

Instead, after that initial investment, Muller came to B.C., and Brooks took him on a trip to Whistler, where he pitched another, different business opportunity.

“He was just wining and dining me,” recounted Muller, who didn’t know the man he was in business with had gone bankrupt and was soon to be under investigation by the RCMP Commercial Crime Section.

Brooks’s pitch to Muller was the purchase of 650,000 tonnes of gravel for use in the local construction market. He was told it had to happen within 24 to 48 hours, Muller recalled, and it would be a $1 million investment, with an eventual profit of $3.2 million.

He contacted his bankers and made the arrangements, sending US$1 million, (about $1.2 million CA) in February of 2009.

Muller provided the Langley Advance Times with a hand-written breakdown of expenses and projected profits, apparently faxed from Blackcrete Contracting, Brooks’s new company, sent on March 20, 2009. He also showed the Advance Times a funds transfer form authorizing the transfer of $1 million to Blackcrete, dated March 27 of that year.

“In essence, it was a handshake deal,” said Muller, who indicated he was promised a contract would be written up later.

The investment was the biggest single part of what would become a drawn-out, years-long relationship in which Muller says he sent more and more money to Brooks – sometimes because Brooks claimed he feared for his life.

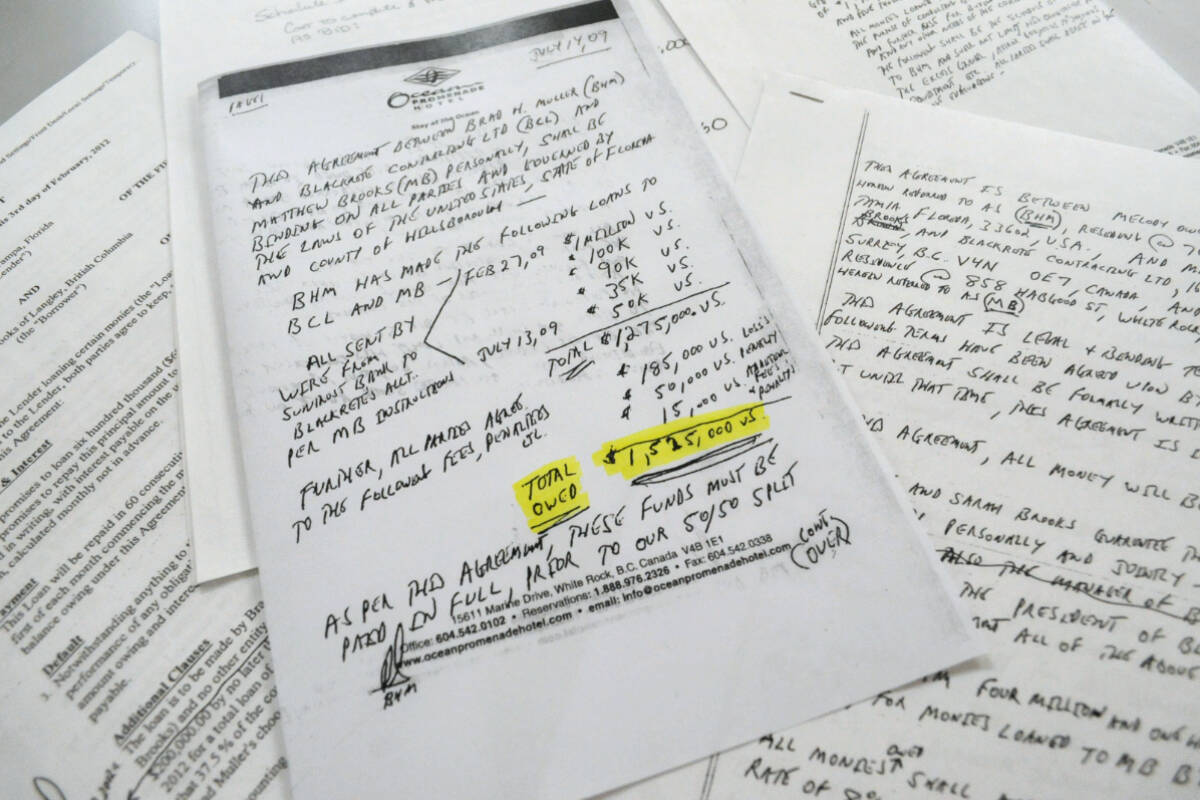

By July 2009, a handwritten contract drawn up by Muller on White Rock hotel stationery showed Blackrete and Brooks owed US$1.525 million to Muller.

Another contract, dated to Oct. 27, 2009, shows the amount owed had risen as high at $4.1 million, including interest.

Copies of the contracts were shown to Brooks, and he acknowledged recognizing them as genuine.

“I guess we both lost a lot,” he said of the business ventures.

Muller wasn’t the only person who lost a large sum of money to Brooks in the aftermath of the Aggressive bankruptcy.

Strato Malamas loaned $1.1 million to Brooks, specifically to a company called M. Brooks Enterprises (MBE) in 2007 and 2008, just before Brooks declared bankruptcy. The Aggressive fraud was underway by then, but it had not yet been discovered by the auditors.

After a first loan of $570,000 was largely paid off in the latter half of 2007, Brooks reportedly came back and asked for more money, this time a further $950,000, for three months at a 55-per-cent interest rate.

“He had a big presentation, glossy pics,” Malamas recalled of Brooks’ pitch.

The plan was straightforward – Brooks said he was buying a gravel pit with the money, a deal similar to the one Muller said he was pitched.

“He comes across like he’s a pretty good guy,” Malamas said of Brooks.

But there was never any return on this investment.

“He never made one payment,” Malamas said, but he wasn’t initially worried about getting his investment back.

“It was all secured by real estate,” he noted.

The properties securing the loan were an industrial property in Surrey and a vacation home in Whistler.

Malamas sued to get his money back, but the case dragged on. It turned out some of the land Brooks had used as collateral didn’t belong to him – the vacation home was a condo belonging to AKS Trucking, a firm owned by Dave Shokar, a long-time contractor for Brooks’ paving businesses.

When Brooks defaulted on Malamas’s loan, Shokar was pulled into litigation with Malamas. Brooks couldn’t be sued, as he was bankrupt by that time. Shokar eventually won in court and kept the condo. Malamas recovered $242,000 from a foreclosure against another building, but lost everything else.

“I just would rather have never met the guy,” Malamas said of Brooks.

Malamas said police never contacted him, and he never contacted police.

The industrial building that Malamas targeted in his lawsuit was the centre of another dispute that year, too.

Court records show that while Brooks was borrowing money from Malamas, he also arranged a deal with Shokar, his longtime contractor, to buy the Surrey industrial shop from which AKS Trucking operated.

For a $100,000 down payment and some trucking company stock, Shokar transferred the ownership of the shop to Brooks’ MBS corporation.

The two men had a handshake deal in which 75 per cent of the ownership was to be kept “in trust” for Shokar.

But Brooks turned around and used his interest in the shop to get a $2.07-million loan from Envision Financial.

Shokar used some of the money to invest in his trucking company and pay off a mortgage on the property, but a judge found that $830,000 went to Brooks.

Court records do not shed any light on what happened to those funds.As with the loan from Malamas, Brooks never made a single payment to Envision on the $2.07-million loan, which was issued on Jan. 15, 2008.

The credit union foreclosed on the shop and the land was ordered sold by the courts in July of 2008.

Shokar, according to court records, was left holding a $3-million promissory note against the now-bankrupt Brooks.

A spokesperson for Envision Financial said records that old were hard to access, and it was unknown if police had ever contacted the credit union about the incident.

READ ALSO: Fraud in B.C.: Developer twice convicted in U.S. leaves condo chaos in Langley

Gunfire in Langley

Another unknown that was brought up during the sentencing hearings of Brooks and Roberts was the drive-by shooting of a home where Brooks was living in Langley on Dec. 9, 2011.

According to local RCMP, the shots were reported by neighbours immediately, but responding officers couldn’t locate the house that had been shot.

It was only weeks after the 9-1-1 calls that the house’s landlord discovered bullet holes in the building where Brooks was living, and the landlord called the RCMP.

Local RCMP looked into the incident, but charges were never laid.

Brad Muller also recalled seeing the bullet holes on one of his trips to Canada.

“I don’t know,” Brooks said, when asked who shot at his house.

“There were a lot of people who had invested in the public entities that we were trying to get up, and it could have [been] any, a number of, a hundred people,” Brooks said. “I don’t know.”

Hells Angels ties

When Roberts was sentenced, he accused Brooks of being an associate of the Hells Angels.

Brooks acknowledged that a confirmed member of the Hells Angels, Courtney Vasseur of the Nomads chapter, worked for Aggressive before it went bankrupt, but he vehemently denied that the man ever received any money from the fraud.

“He doesn’t have any of that money,” Brooks said of the defrauded $6 million. “He was working with Aggressive at the time we were doing things, he worked at Blackrete afterwards, but no, he’s got nothing to do with it.”

Brooks admitted he was aware of Vasseur’s Hells Angels membership at the time.

“Yes, but I don’t think he had any benefit of anything I was doing other than getting a paycheque for the work he did,” Brooks said.

“I can’t speak to what happened going forward,” he added.

Muller was aware that Vasseur had a business connection to Brooks, and one he says continued after the Aggressive bankruptcy. Muller encountered Vasseur with Brooks in B.C. between 2009 and 2011.

“I was aware that he was a Hells Angels person almost from the outset,” said Muller. “Matt told me.”

On several occasions, Muller said he told Canadian authorities about Vasseur’s involvement in Brooks’ business.

The first time was when he was still financially entangled with Brooks. Muller had told his wife about some of the things that were going on, and she feared he was in danger. She phoned the RCMP, and officers knocked on Muller’s hotel room door.

He gave them a statement that mentioned Vasseur.

Later, back in Florida after he had cut ties with Brooks, Muller would contact the FBI. The issue was out of their jurisdiction, but they put him in touch with the RCMP, and again he told them about his issues with Brooks, and mentioned Vasseur.

“They knew what was going on,” Muller said.

Yet he says there was no follow up by police with him at any point.

Sgt. Kris Clark, spokesperson for FSOC, couldn’t say if a file was opened based on Muller’s complaints.

“We typically don’t confirm or deny when an investigation has begun on anybody,” he said, explaining that it’s an issue of privacy law.

In April, Vasseur was one of 10 people charged by the U.S. Department of Justice, accused of alleged involvement in a global pump-and-dump stock fraud scheme that netted its participants more than $100 million in profits.

People charged with crimes are considered innocent until proven guilty in a court of law.

Vasseur, a Burnaby resident, is awaiting extradition proceedings.

This is only the second major criminal charge for Vasseur, who has never been convicted of a crime in Canada.

On May 15, 2013, Vasseur’s Cadillac Escalade, driven by Craig Leonard Retvedt, crashed into the back of a bus at Cambie and 16th in Vancouver. Both men were discovered passed out due to accidental fentanyl overdose – an open baggie of the drug was found in a console between the seats. Both men were charged with possession of fentanyl for the purpose of trafficking.

“One of the two men clearly was in possession of at least the powder, and possibly both of them were,” Justice Heather Holmes noted in her 2017 ruling. But there was not enough evidence to tie it to either man, so both were found not guilty.

READ ALSO: Fraud in B.C.: Who investigates when millions go missing?

‘Follow the money’

Muller eventually gave up on ever getting any of his US$2 million back.

During the last few years, he said he has approached RCMP in B.C. multiple times seeking an investigation of his case, but said he has been repeatedly rebuffed.

He said the loss of the money ruined him financially. He has since declared bankruptcy and lost his hotel business. Muller is barely scraping by these days, he said.

“He ruined my life,” Muller said of Brooks.

Muller wants to know what happened to all the money he poured into investments with Brooks over several years, and why the RCMP won’t look into it.

“Follow the money” is Muller’s mantra. He is intensely frustrated at what he sees as a lack of action by Canadian police.

Whatever happened to the money, from the Aggressive fraud or the loans, or the investments by Muller and Malamas that were never paid back, Brooks did not have any of it by the time he was sentenced in 2018.

Brooks arrived for his sentencing hearing carrying his personal belongings with him in a cloth Walmart shopping bag.

His lawyer told the court that Brooks was working part time as a landscaper, and was living either in a trailer, or with family and friends.

“To all intents and purposes, Mr. Brooks has lost everything,” said Stephanie Head, who represented Brooks at his last few hearings.

“The Crown was not able to determine what happened to the money,” Crown attorney Brian McKinley said at Brooks’ sentencing hearing.

During the sentencing hearing, Brooks lashed out verbally at his former business partner Roberts.

“Ask [him] where the missing money is, and who his business partners are!” Brooks said.

In turn, Roberts pointed the finger at Brooks when it came time for his sentencing.

During Roberts’ sentencing arguments, the judge heard that Brooks “treated the business bank account as his own,” withdrawing money and sometimes depositing money from non-business sources, according to Roberts’ defence lawyer Ian Donaldson.

“The best thing that happened to me is that I went to prison,” Brooks told the Langley Advance Times, during an interview while he was taking a break from his job as a landscaper, spreading soil on new planting beds near a Surrey park in 2022.

“At the end of the day, I own a 20-year-old one-ton dump truck, and a few shovels, and wheelbarrows, and I go to work every day,” he said.

He acknowledged that other people lost money due to his actions.

“I made my mistakes, and I believe that everybody that knows me knows that I didn’t benefit from any of their losses,” he said.

Asked what happened to the missing millions, he said to follow the money.

“Do your job, follow the money. See who has it,” Brooks said. “You know, if you open your eyes, you can see it, it’s right there.”

Sig