By Alexandra Mehl, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter HA-SHILTH-SA

Despite high prevalence rates of diabetes in First Nation communities, gaps in education and healthcare services prompt diabetes educators to bolster culturally safe, Indigenous-led and accessible services for people with the condition.

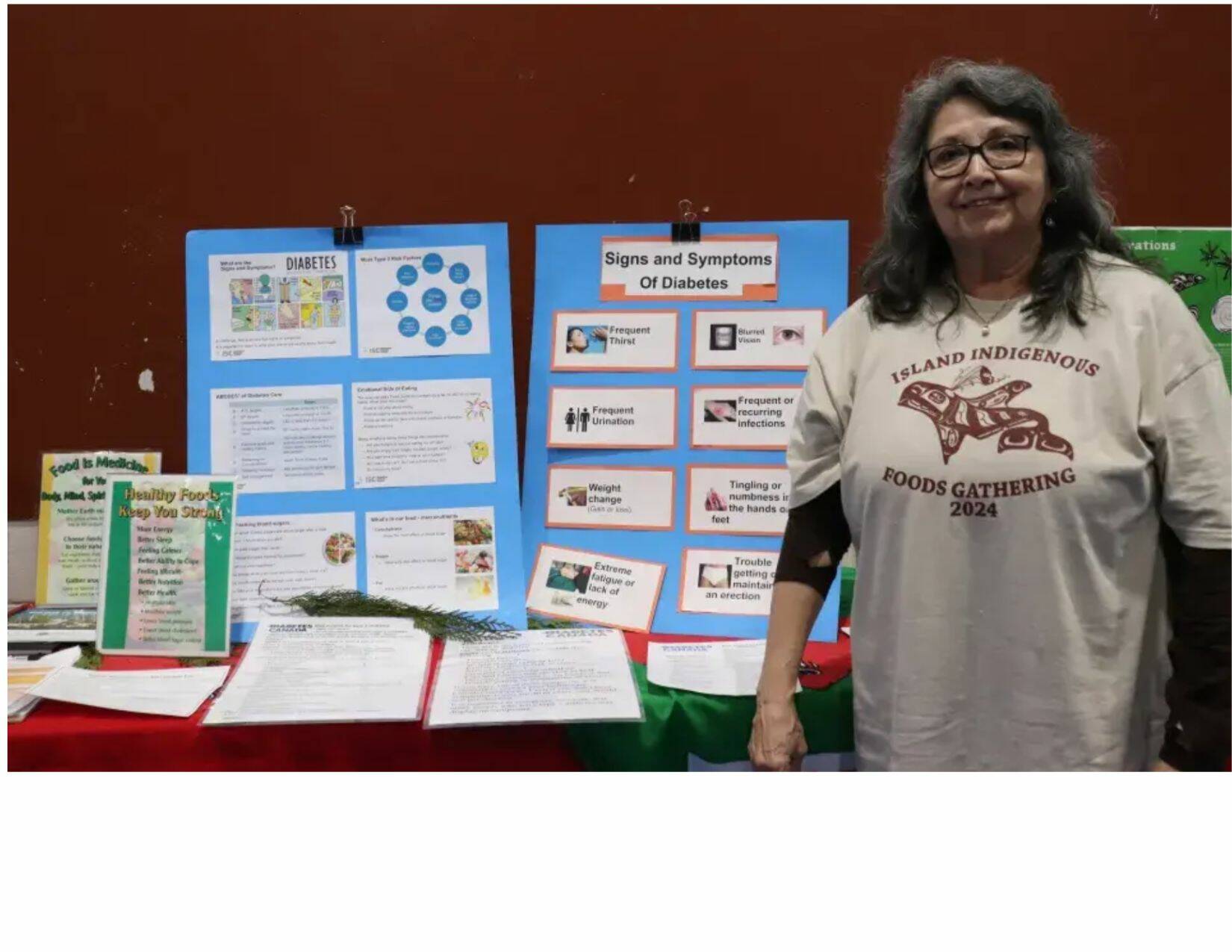

Matilda Atleo, an Indigenous educator in diabetes for First Nations Health Authority (FNHA), takes every opportunity to educate people about the disease.

“I’m aware that there are people that have diabetes and don’t even know it,” said Atleo. “There’s likely a high prevalence of diabetes in First Nations.”

“Just being First Nation you’re at risk,” she added.

According to Diabetes Canada, due to the “intersecting factors” of historic colonial policies, barriers in accessing healthy and affordable food, alongside a genetic predisposition for type 2 diabetes, First Nations are at a higher risk in developing the disease (type two).

While 17.2 per cent of Indigenous people living on reserve are impacted by diabetes (type one and two), the prevalence rate for off-reserve First Nations sits at 12.7 per cent. The national rate is 10 per cent, according to Diabetes Canada.

Since last fall the FNHA has been engaging with First Nation communities on Vancouver Island to develop an Island-wide diabetes strategy.

“There are a lot of gaps in service, there’s that big need,” said Atleo. “Even just awareness.”

Atleo envisions accessible health care where First Nation people can access diabetes testing and screening outside of a hospital environment.

“They prefer to go to someplace where they feel comfortable,” said Atleo.

First Nations who are diagnosed with diabetes are not getting the education they need in western healthcare systems, according to Atleo.

“A lot of people are not getting the education… as soon as they’re diagnosed to know what they need to do,” she said. “I’d love to see us doing some sort of traveling .125on.375 the Island to different communities, different regions and doing screening.”

Atleo notes that it’s important First Nations people have a place to access services where they feel safe and not experience shame or worry about being treated poorly and not be listened to.

“People would be so willing to come,” said Atleo. “I think it gives them hope, and they say, `There are people that really care’.”

Rachel Dickens is a dietician with the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council. She echoes Atleo, sharing that when it comes to diabetes information, it can be confusing and hard to access.

In May of 2022, 74 Nuu-chah-nulth representatives gathered with FNHA and Island Health to develop a Nuu-chah-nulth lead approach to diabetes, shared Rachel Dickens, who is Ts’msyen of the Lax Kw’alaams First Nation.

Since then, a committee consisting of Dickens, Ahousaht’s traditional food advocate Nitanis Desjarlais and the Uut Uuštukyuu Society’s Erin Ryding organized a diabetes retreat with an aim to support families managing the disease while connecting them to traditional foods and ceremony.

“As far as we know, diabetes retreats aren’t happening,” said Dickens.

“I think the goal… for the retreat is giving the information broadly out to different generations so that this information is within communities,” said Dickens.

When Dickens reflected on the impact of the retreat she shared some of the comments made by those in attendance.

“I realize my worth, I’m valuable, I need to care for myself,” she observed. “Some people .125said.375, `I’ve never not had juice for four days straight, or this is the least amount of salt I’ve eaten, I feel so good’.”

The retreat was held over a period of four days, with ceremonies interwoven throughout, said Dickens. Hunters and harvesters provided traditional foods like seal, while an Ahousaht chef prepared meals.

“We treated diabetes like a family,” said Dickens. “Something a family should kind of understand rather than just the individual.”

“It’s overwhelming and scary,” said Ahousaht member Angus Campbell of the learning that comes with a diabetes diagnosis.

Campbell doesn’t always have the time to read about diabetes, but when Dickens takes the time to sit and talk with him about the disease, it makes a difference.

“It took a while before I realized .125Dickens.375 was there,” said Campbell. “The help that she’s been, it seems like it’s a different atmosphere.”

“It’s just about a pandemic when you have that many people that have diabetes,” said Campbell. “We need to get people to know it’s our eating habits that get us to where we are.”

READ ALSO: ‘Life changing’: People with diabetes greet treatment coverage with joy