After years spent fighting and studying wildfires, it’s become clear to Jen Beverly that Canadians must begin prioritizing how best to evacuate entire communities.

Beverly, an associate professor at the University of Alberta who specializes in fire behaviour research, believes Canada lags in fuel mitigation efforts that might prevent, or at the very least stall, fires such as the one that destroyed neighbourhoods last summer in West Kelowna.

What communities should focus on, she says, is the immediate safety of residents.

“You lose a couple 1,000 homes every year to wildfires. It’s horrible. But if you can keep everybody safe and just get them out, then you rebuild and you regroup. If that’s the inevitable, then we just have to keep people safe.”

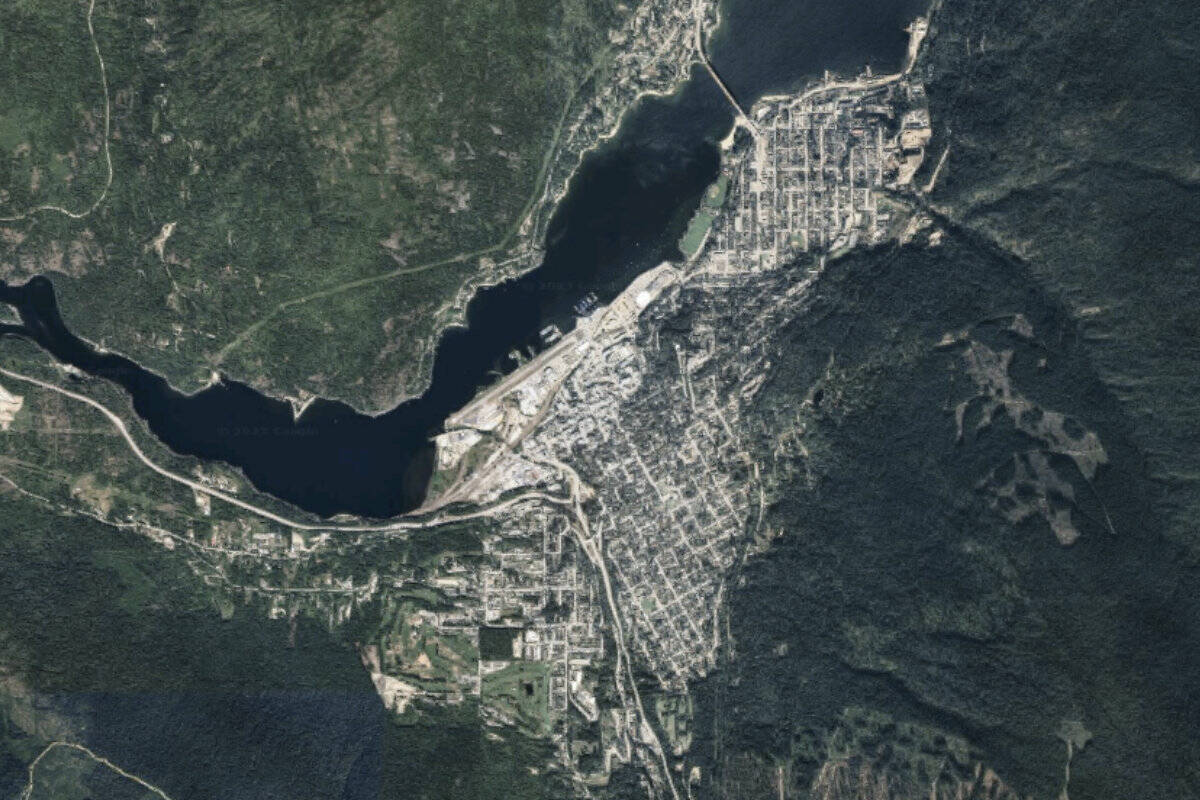

Beverly and her colleagues Stephen Wong and Amy Kim are the researchers behind a unique study funded by Infrastructure Canada that is building wildfire evacuation simulations for three B.C. communities — Nelson, Salmon Arm and Quesnel — as well as Canmore and Whitecourt in Alberta.

The project analyzes transportation corridors in each community and will make recommendations not only for how they might be improved in the case of a mass evacuation, but also for potential best practices that might be used elsewhere in Canada.

Beverly said there is a dearth of Canadian research on how wildfires impact people.

“We are dealing with a crisis here when it comes to fire impacts to people. We don’t have the models that we need. We don’t have the science that we need, and we don’t have the data. … There’s nothing to help us prepare really for what could unfold.”

Part of what makes the study unique is that it mixes various sciences: While Beverly’s background is in fire research, Kim is a civil engineering assistant professor at the University of British Columbia whose interest is in long-distance transportation systems.

Wong, meanwhile, works as an assistant professor at the University of Alberta specializing in how humans behave during evacuations.

“There has been a good amount done on the fire science side, not so much on the evacuation side from a Canadian context, just a few examples out there of research,” Wong said. “So I think this is the first time we’re thinking about it holistically.”

The five communities included in the study were chosen by several criteria. None of them have been impacted by wildfires yet, but have been assessed as having high exposure to fire and have populations between 5,000 to 25,000 – because Canadian wildfires typically impact smaller communities (larger cities wouldn’t work with the team’s modelling simulations). As well, each community included would possible struggle in an evacuation due to a lack of transportation options.

The locations are also economically diverse, which can vary what types of vehicles are on the roads. Nelson and Canmore are tourist oriented, Wong said, while Quesnel and Whitecourt rely on the lumber industry. Salmon Arm was judged to have aspects of both.

FireSmart experts in B.C. and Alberta were also consulted and could advise on places where residents would be eager to participate in the study.

“[Whitecourt] is considered a real progressive community when it comes to FireSmart efforts and has a very engaged fire chief,” said Beverly. “They’ve done a lot of work there with fuel management, documenting the problems and so on. That’s a community that would embrace this kind of work.”

How people plan to flee during a wildfire is the focus of Wong’s contribution.

He’ll ask participants questions, such as where they intend to go, what mode of transportation they will use, which route they take and the type of shelter they plan to stay in. Residents will also be surveyed on if they are physically or financially unable to leve quickly.

Wong has previously studied wildfire evacuations in California, and determined that two-thirds of evacuees remained within their county of residents. They also didn’t panic.

“People generally evacuate orderly. They might make decisions that, based on their stress and their risk perceptions, might not necessarily be as quote-unquote safe like driving on the other side of the road, but it’s usually not under some type of panic condition is the big key.”

His recommendations to Infrastructure Canada, he added, will be tailored to predicting those behaviours rather than trying to change them.

Kim is studying existing infrastructure and will build simulation models that examine where efficiencies might be found.

On a low-volume road, traffic will flow well, she said as an example, while additional vehicles decrease overall speed, but so do existing traffic controls, such as crosswalks and lights. Geography also matters because it determines where roads can be built as well as their capacity.

“The configuration of all those roads and all those egresses out of a city or town will determine how many people can go through, amongst a lot of other things,” she said.

There are several potential solutions that Kim will be exploring with each community’s highways.

Traffic lights may be kept green on major arterial roads, and entry points could be controlled to keep vehicles moving. Two-way lanes might be changed to one way in order to double capacity, but that comes with a need for people or devices present to make sure traffic is flowing as it should. It also doesn’t offer a lane for emergency vehicles moving the opposite way.

Kim said simply increasing speed limits isn’t a safe option for evacuations. Variable speed limits have been shown to ease congestion when lowered, but increasing a 90 km/h sign, for example, wouldn’t work.

“Speed limits are set with a lot of design criteria in mind. … They’re set to make sure that most of the driving population can travel that speed safely. So increasing speeds, I don’t think that would be a solution or an option.”

The original deadline for the study’s recommendations was March 2024, but Wong said he believes it will be extended by a year.

When released, it will come with recommendations that not only prepare for wildfire evacuations in each of the studied communities but that can also be applied throughout Canada.

“Sometimes we won’t always have the exact answers for everything,” said Wong. “The best we can do sometimes is prepare and plan as best as we can.”

READ MORE:

• FireSmart is key to structural protection, Canadian Wildfire Conference

• Alberta taps into AI to predict wildfires before they erupt

• Lytton artifacts latest roadblock to a rebuild as residents rally

• ‘They ran for their lives’: John Vaillant to speak about new wildfire book in Nelson