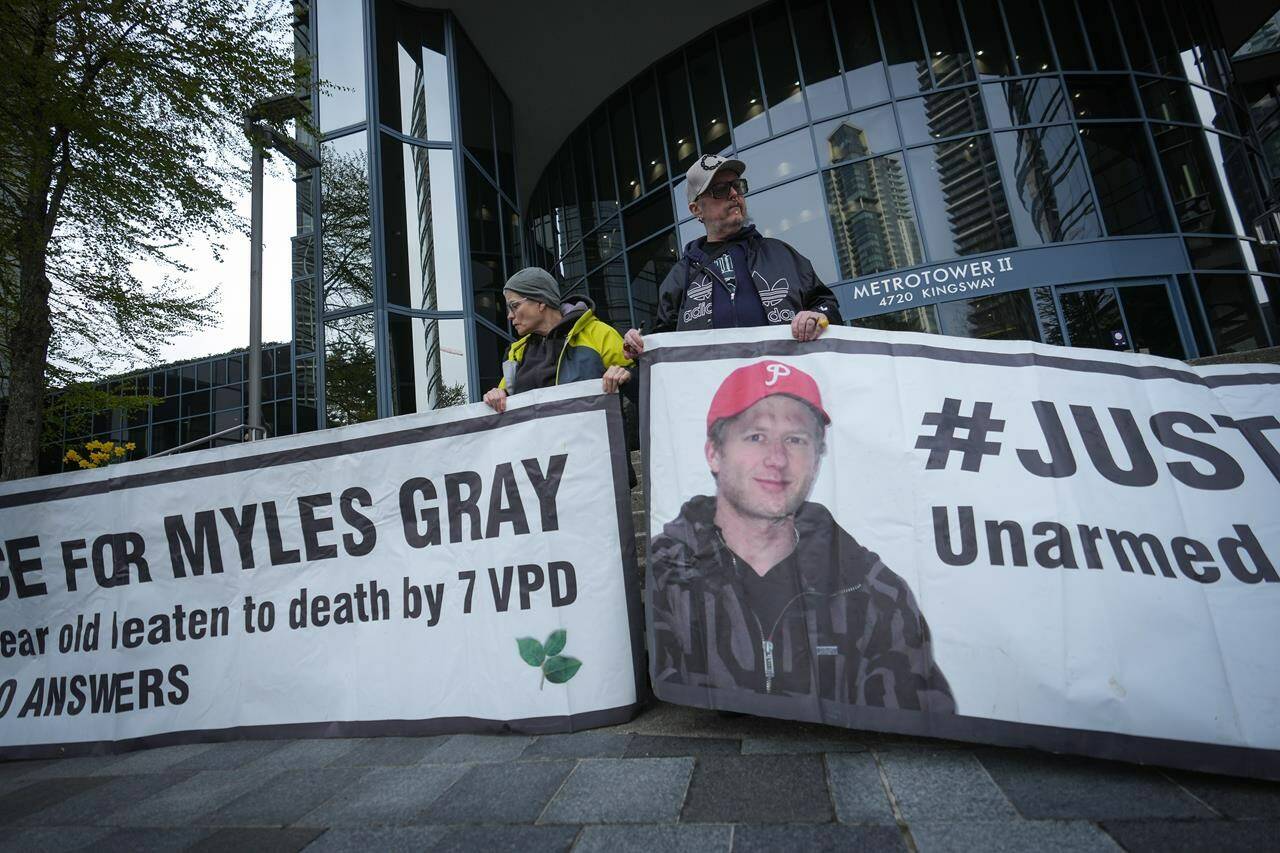

The jury at a British Columbia coroner’s inquest began deliberating Monday at the end of 11days of testimony about the death of Myles Gray after a beating by Vancouver police officers nearly eight years ago.

Coroner Larry Marzinzik reminded jurors they are not to make any findings of legal responsibility when determining their possible recommendations.

Gray, who was 33, died in August 2015 after a beating by several officers that left him with injuries including ruptured testicles and fractures in his eye socket, nose, voice box and rib.

Marzinzik tasked the jury with classifying Gray’s death and explained the five categories: natural death, accidental death, suicide, homicide or undetermined.

He said homicide refers to a death due to injury intentionally inflicted by another person, but it’s a neutral term that doesn’t imply fault or blame.

An accidental death is due to unintentional or unexpected injury and a natural death is due to disease, not resulting secondarily from injuries or environmental factors.

Dr. Matthew Orde, the forensic pathologist who performed an autopsy on Gray, testified last weekthat a “perfect storm” of factors led to his death, including his extreme physical exertion while police tried to restrain him.

Gray was also experiencing an “acute behavioural disturbance,” Orde said.

He concluded that Gray died of a cardiac arrest complicated by police actions, pointing specifically to “neck compression,” blunt force injuries, the use of pepper spray, forcing Gray onto his stomach and handcuffing him behind his back.

“In the context of someone who’s extremely fatigued, (whose) body is fully ramped up … I think these issues would be enough to tip him over the edge,” Orde told the jury on Thursday.

The inquest heard from 42 witnesses, including 14 Vancouver police officers and Gray’s sister, Melissa Gray, who described her brother as kind, goofy and loyal.

She said Gray had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder around 1999, but he’d been stable ever since.

The initial 911 call was about an agitated man who had sprayed a woman with a garden hose.

The inquest heard testimony spanning the first moments police encountered Gray to first responders’ efforts to revive him after he stopped breathing.

Officers told the inquest they first tried to talk with Gray, but the situation escalated quickly after his demeanour changed and he moved toward them.

One officer deployed pepper spray, while another described hitting Gray in the face as hard as he could because he didn’t think anything else would work to subdue the man long enough to get him into handcuffs, other than shooting him.

Officers who arrived later said Gray didn’t seem to feel any pain as they struck him with their batons and knees. They told the inquest he displayed “superhuman strength” and he was yelling and grunting in an “animalistic” way as he struggled.

By the time Gray was handcuffed, most of the officers told the inquest they didn’t notice any signs of injury besides redness in his face and some body bruising.

However, Stephen Shipman, an advanced life support paramedic, said he arrived and saw bruising so severe, he initially thought Gray was not a white man.

Burnaby firefighter Scott Frizzel said Gray looked like he’d been in a “battle.”

Another Burnaby firefighter, Lt. Young Lee, said an officer led him to the yard where Gray was handcuffed and struggling as police held him down.

Lee testified that one of those officers said firefighters couldn’t yet move in to assess Gray’s condition because he was still “combative.”

Speaking to media outside the inquest last week, Margie Gray said her son was not combative, rather “he was fighting for his life to get a gulp of air.”

A years-long investigation by B.C.’s police watchdog found reasonable grounds to believe an offence may have been committed and it submitted a report to the BC Prosecution Service for consideration of charges.

The service announced in late 2020 that it would not pursue charges against the officers involved in the struggle to arrest Gray, saying police were the only witnesses and the Crown couldn’t prove any offence had been committed.

—Brenna Owen, The Canadian Press

READ MORE: Forcible restraint by police among factors in Myles Gray death, pathologist says

READ MORE: Eight years on, inquest into police-linked death of Myles Gray to begin in Burnaby