Editor’s note: The story below may trigger difficult or traumatic thoughts and memories. The Indian Residential School Survivors Society’s 24-hour crisis line is available at 1-866-925-4419.

When Daryl Verville was a child, he’d lay in bed at night and think about killing his father.

From his room, he could hear Douglas berate Daryl’s mother Jeanne. Night after night, Douglas would scream insults until Jeanne cried.

The abuse kept Daryl up in fear, and was so routine that he developed insomnia and anxiety. When he was seven, Daryl grabbed a knife and in the night crawled under his parents’ bed while they slept. There he tried, and failed, to find the courage to murder Douglas.

Douglas also took out his anger on the children, sometimes with beatings. Daryl remembers his brothers Paul and Dennis sneaking into the house at night through bedroom windows so they wouldn’t have to walk past their father.

His father’s temper made Daryl wary of other male adults, and confused if they showed any kindness.

“Why are these guys nice, and why is my dad the way he is? It troubled me through my whole childhood.”

While Douglas was a monster in his son’s eyes, he was also a mystery. Daryl knew nothing about his father’s past. Only once did he meet his grandfather Joseph, who came knocking as an old man. But Douglas wasn’t home, and two weeks later Joseph died.

Douglas died of cancer in 1992, but remained a figure of terror for Daryl even after his passing. Daryl tried to find his own answers, and thought he had them in 2013 when he approached his mother. A student of Carl Jung’s theories, Daryl used what he knew of psychology to deduce his father had been sexually abused as a child and asked Jeanne if he was right.

“I’ll never forget the way she looked at me. She looked at me and she must have had that thought, ‘He knows.’”

At the time of their engagement, Douglas told Jeanne his secret. When he was four years old, he and his two brothers had been taken to Youville Residential School in St. Albert, Alta.

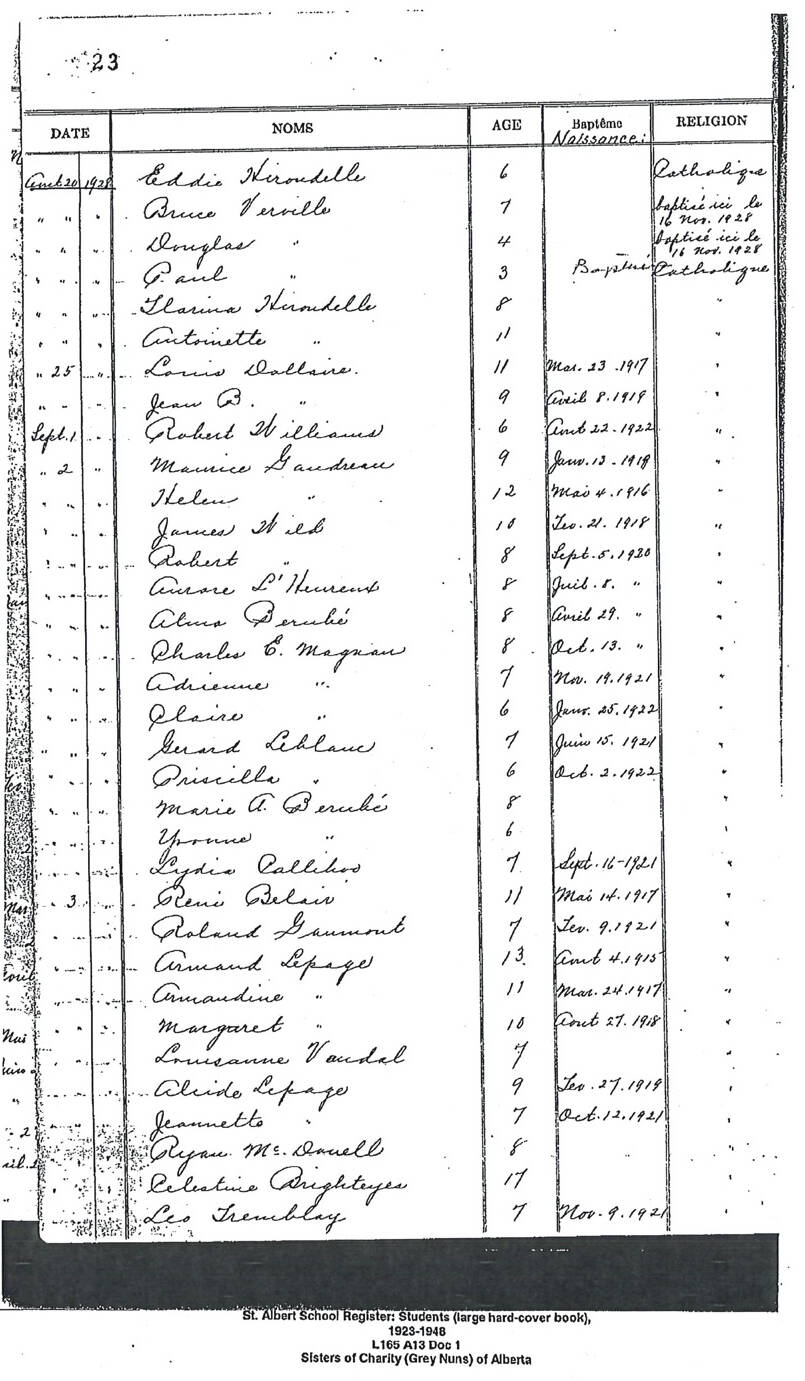

Records provided to Daryl by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission show the children were at the school from 1928 to 1931. Daryl also believes Douglas was moved to Blue Quills Indian Residential School in St. Paul, Alta., and stayed there through high school, but has no records to prove it.

Douglas confided in Jeanne that he was forced into manual labour at the school. Punishments for any mistakes, either real or trumped up by the Roman Catholic priests and nuns who ran the school, were met with whippings. Children would be slapped or punched and have their hair pulled. Sometimes they would be sent out into the prairie winter without a jacket and made to freeze.

And they were raped.

Douglas was one of an estimated 150,000 First Nations, Inuit and Métis children who attended residential schools in Canada in the 20th century. The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation has documented at least 4,100 deaths, with more expected to be confirmed as former school sites are searched.

Douglas made Jeanne promise she would never tell anyone about his childhood. She kept her word until Daryl pressed for the truth in 2013. Jeanne died two years later.

Could have been, should have been

Daryl Verville is 65 years old and lives in a small apartment in Nelson. It’s a cluttered place due to the well-used piano he has made space for just inside the front door.

The instrument has been an anchor for Verville since his was a child. Jeanne was an accomplished pianist and taught her children, but only Daryl saw the piano as an opportunity for a better life. He found inspiration in the Romantic composers such as Beethoven, Chopin and Brahms, and admired their willingness to write music that wasn’t influenced by church.

The Verville boys were “wild,” as Daryl describes it now. All three were petty criminals who got into drugs at a young age — Daryl recalls an acid trip when he was just 12 years old.

His father kicked Daryl out of the house when he was 15, but Daryl maintained a close relationship with his mother.

When he was as a teenager, Jeanne took him to the University of Alberta’s Department of Music. There he played a Spanish piece for Dr. Ernesto Lejano. During the song, Lejano interrupted Daryl and shooed him off the bench. Lejano began playing the same song, and Daryl was mesmerized.

“I just sat there and stared in total awe. I really did. He was an artist.”

Daryl was still in high school but began studying with Lejano. He earned a scholarship to the university and believes he was being groomed for a promising career. But the anxiety he developed as a child seemed to get worse before public performances. He’d stay up late, unable to sleep, and when it was time for the concert he was wracked with stress.

Daryl dropped out of school in his second year. He married a woman in Edmonton and began a water purification business. But in the early 1980s his business was struggling. A friend offered him a job as a drug runner, moving cannabis over the B.C.-Alberta border. Daryl took it, and for four years made his living trafficking first pot then cocaine.

He was never arrested, but two overdoses scared him straight. His marriage had ended (Daryl’s ex-wife now lives in New Denver; the pair have remained close) and Daryl moved to Nelson in the mid-1980s to be near his brother Paul, who was teaching music in the city.

In the following decades, Daryl would help form a land co-op in the Slocan Valley and become a father to three children. He also tried returning to performances, and partnered with a dancer for a series of shows. But at each concert, Daryl wore a mask when he would take a seat at the piano. It was the only way he could play.

“I couldn’t get in front of people if I thought they could see me.”

Living with the past

The revelation about his father has not brought Daryl any peace, but it has given him some clarity.

He no longer blames Douglas for how he treated the family, and has found compassion for the man he used to despise.

“On a spiritual level, I know my father wasn’t to blame at all. He never got therapy, which he should have. So the love that I feel for him, rather than the hate, changes a lot of things.”

But Douglas’s background remains a mystery. Daryl doesn’t know which First Nation Douglas belonged to, and the men who would have been his uncles died decades ago.

Jeanne was Mohawk, but as a devote Catholic the culture she prized was of the church. Daryl identifies as Indigenous and spent years immersing himself in different First Nations cultures in Canada and the United States. But what he really is, he says, is a shipwrecked orphan who doesn’t feel Canadian.

At the suggestion of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, Daryl published a memoir in 2020 titled Epistles to the Pope: A personal history of perilous priestcraft. The book is divided into a series of chapters that address both the papacy and Pope Francis, who earlier this month apologized for the role the Roman Catholic Church played in residential schools.

Religion is complex for Daryl. He has begun attending a church near Nelson but places little faith in the Pope, whose apology without the promise of reparations didn’t resonate with him.

Daryl still struggles to perform in public. A concert he had scheduled at Nelson’s Capitol Theatre for April 15 has been postponed by his insomnia and anxiety. Instead, he plans to film a performance at the venue and release it online.

Nearly a century ago, a four-year-old boy was taken from his family. The chords of that crime will reverberate throughout the rest of Daryl’s life.

“In a way, the church stole something from me. I should have had a life. … I had a condition that prevented me from giving my gift. Now I’m saying, OK, I could give my gift. That’s the healing, and that’s why I need to do it. I want to be who I am.”

READ MORE:

• Stólō Tribal Council embarking on interview project for survivors of St. Mary’s Residential School

• ‘Never losing hope:’ Former national chief says apology reflects decades-long fight

@tyler_harper | tyler.harper@nelsonstar.com

Like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.