The last of three men convicted of hijacking a school bus full of California children for an attempted $5 million ransom in 1976 — in what a prosecutor called “the largest mass kidnapping in U.S. history” — is being released by the state’s parole board.

Gov. Gavin Newsom asked the board to reconsider its decision to parole Frederick Woods, 70, on Tuesday. Two board members recommended his release in March when previous panels had denied him parole 17 times. But the board affirmed that decision.

Woods and his two accomplices, brothers Richard and James Schoenfeld, were from wealthy San Francisco Bay Area families when they kidnapped 26 children and their bus driver near Chowchilla. The town is about 125 miles (201 kilometers) southeast of San Francisco.

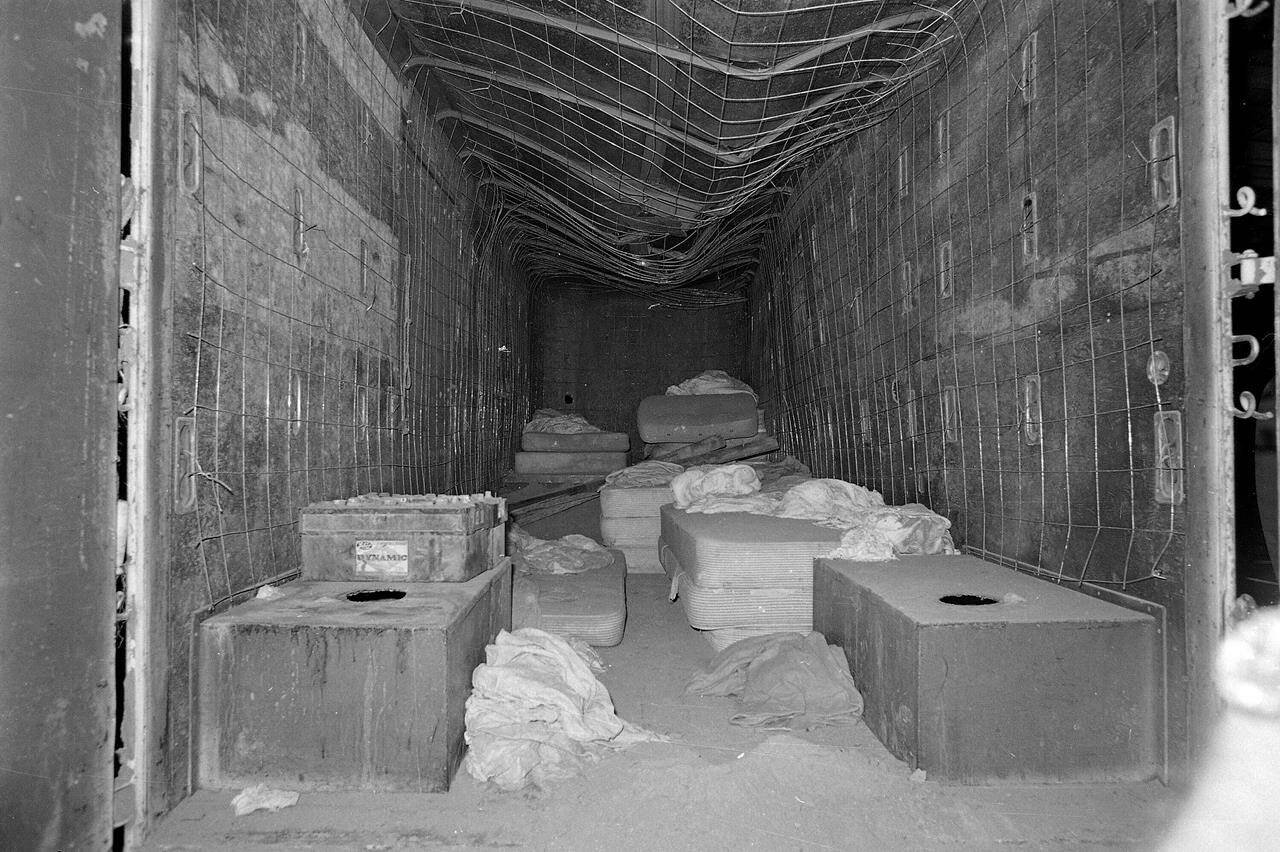

The three buried the children, ages 5 to 14, along with their bus driver in an old moving van east of San Francisco with little ventilation, light, water, food or bathroom supplies. The victims were able to dig their way out more than a day later.

Newsom said Woods “continued to engage in financial related-misconduct in prison,” using a contraband cellphone to offer advice on running a Christmas tree farm, a gold mining business and a car dealership. The governor couldn’t block Woods’ release because he’s not convicted of murder, and could only urge the parole board to take a closer look.

Woods’ behavior “continues to demonstrate that he is about the money,” Madera County District Attorney Sally Moreno said in opposing his parole.

Moreno said after the decision that she was angry and frustrated “because justice has been mocked in Madera County,” and she fears for the state of society “if you can kidnap a busload of school children, abandon them buried alive and still get out of prison after committing that crime and spending your time in prison flouting the law.”

Woods wasn’t eligible to attend in person on Tuesday. But he said during his parole hearing in March that he felt he needed money to have acceptance from his parents and “was selfish and immature at that time,” while his more recent violations were to benefit the trust fund left him by his late parents.

“I didn’t need the money. I wanted the money,” Woods said of the ransom attempt.

His attorney, Dominique Banos, said Wednesday that the parole board recognized that Woods “has shown a change in character for the good” and “remains a low risk, and once released from prison he poses no danger or threat to the community.”

Three former inmates who served time with Woods urged parole officials to free him, while four victims or their relatives said Woods’ misbehavior in prison shows he still views himself as privileged. Several of Woods’ victims have previously supported his release.

Lynda Carrejo Labendeira, who was 10 at the time, recalled how the children struggled to escape as a flashlight and candles flickered out while “the makeshift, dungeonous coffin was caving in.”

“I don’t get to choose the random flashbacks every time I see a van similar to the one that we were transported in,” she told the board.

“Insomnia keeps me up all hours of the night,” she said. “I don’t sleep so that I don’t have to have any nightmares at all.”

Jennifer Brown Hyde, who was 9 at the time, recalled “the lifetime effects of being buried alive and being driven around in a van for 11 hours with no food, water or a bathroom in over 100-degree weather.”

“His mind is still evil and he is out to get what he wants,” she told the board. “I want him to serve life in prison, just as I served a lifetime of dealing with the PTSD due to his sense of entitlement.”

She said Wednesday that her family is disappointed, but it is “time to close this chapter and continue living the blessed life I have been given.” She praised her fellow hostages as “true survivors and not victims.”

An appeals court ordered Richard Schoenfeld released in 2012, and then-Gov. Jerry Brown paroled James Schoenfeld in 2015.

Newsom acknowledged that Woods is eligible for consideration both because he was just 24 when he committed the crime and because he is elderly now. He said Woods, who once studied policing at a community college, has also taken steps to improve himself in prison.

The governor’s late father, state Judge William Newsom, was on an appellate panel in 1980 that reduced the men’s life sentences to give them a chance at parole. He pushed for their release in 2011, after he retired, noting that no one was seriously physically injured during the kidnapping.

– Don Thompson, The Associated Press