The sacrifices of Canadians who fought and died for democracy and freedom during the Korean War were honoured during a small ceremony last week at the National War Memorial.

The ceremonial plaza, located a stone’s throw from Parliament Hill and which includes the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, was built for such acts of remembrance.

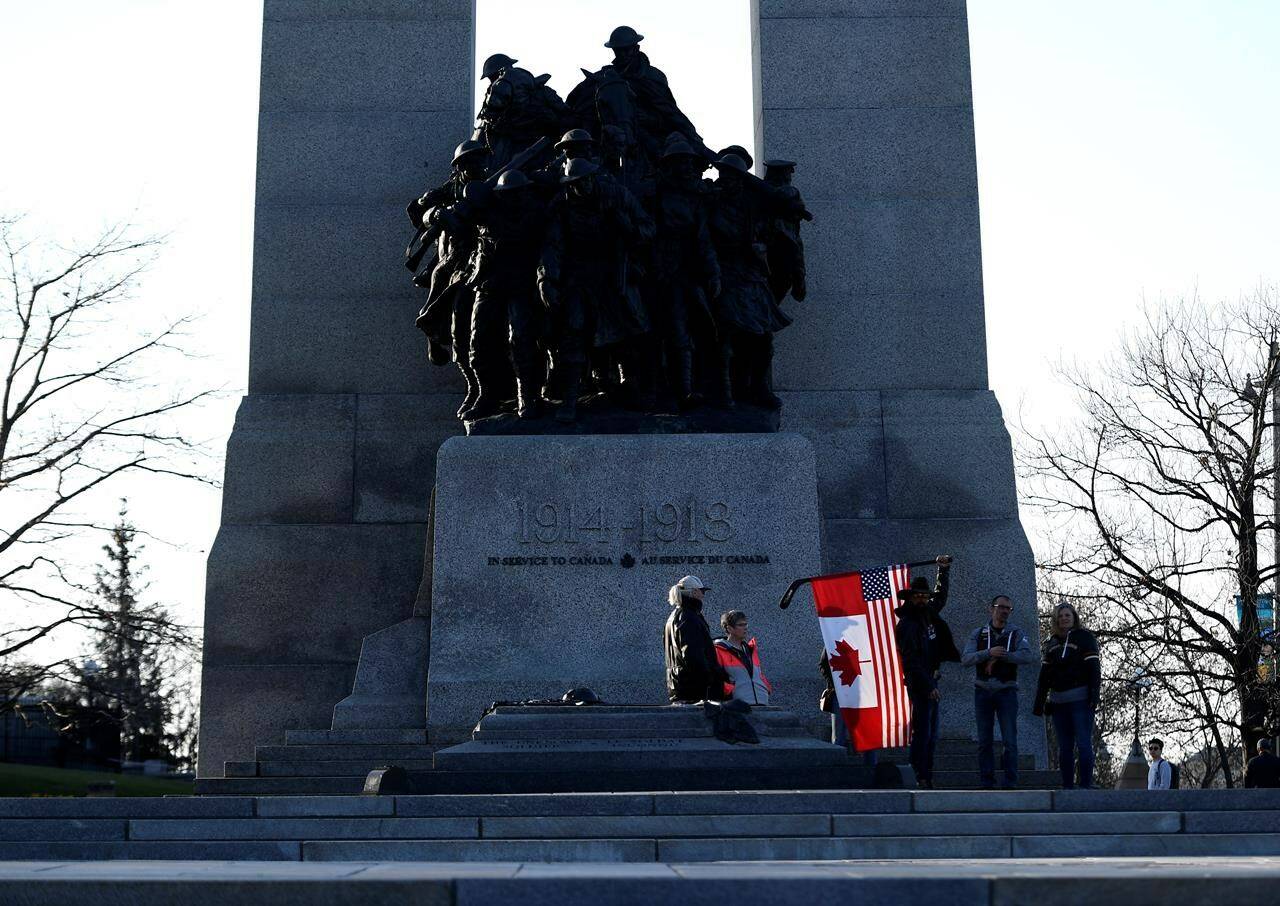

This year, though, Canadians have seen far different images of the memorial, including acts of vandalism, and as a rallying point for those opposed to COVID-19 vaccine mandates and the Liberal government of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

It has sparked concern about the sacred site dedicated to Canada’s war dead being used for political purposes, and a debate around what steps could be taken to better protect it.

Last weekend, someone was seen draping Canadian and American flags on the tomb as part of a ceremony streamed live online. Photos and video were widely shared on social media before the accounts, which appeared linked to supporters of the “Freedom Convoy,” were closed.

It sparked an outcry, including from Defence Minister Anita Anand, who called it a “desecration.”

It also prompted calls for more security, including from the Royal Canadian Legion, which had first made such a demand after the memorial was seen as disrespected, including through public urination, near the beginning of the three-week protest that seized downtown Ottawa this winter.

On the eve of Canada Day, army reservist James Topp addressed hundreds of people gathered by the cenotaph and compared himself and others fighting vaccine mandates to the unidentified Canadian soldier killed in the First World War whose remains were buried in the tomb.

Facing a court martial for publicly criticizing federal vaccine requirements while wearing his uniform, Topp had arrived at the tomb following a four-month march from Vancouver, during which he became a celebrity to many people opposed to vaccines and the Liberals.

“That’s us. We are the Unknown Soldier,” Topp told the crowd, which included a number of people wearing military headgear and medals to indicate their status as veterans.

“What did we have in common with that person? … We had courage.”

READ ALSO: Remaining protesters say they will not leave until all COVID restrictions are lifted

A group called Veterans 4 Freedom, which supported Topp’s march and includes members with links to the “Freedom Convoy,” also organized a rally at the memorial during the “Rolling Thunder” event in April, where members gave speeches against vaccines and pandemic restrictions.

“Canadians have to sacrifice to keep our freedom,” one speaker told the crowd. “They went to France. They fought in the South Pacific, the Battle of Britain. They sacrifice with their lives. But nowadays, we have to sacrifice in a different way.”

Veterans 4 Freedom declined to comment. Topp referred to his June 30 speech.

David Hofmann is an associate professor at the University of New Brunswick and co-lead of the government-funded Network for Research on Hateful Conduct and Right-Wing Extremism in the Canadian Armed Forces.

He said political movements need symbols to succeed, and that it perhaps shouldn’t be a surprise that some groups in Canada are now trying to turn the National War Memorial and the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier to such purposes.

“It is a powerful symbol,” Hofmann said. “You have the Unknown Soldier, the ultimate martyr, someone who can’t even be remembered for their name. And you have these individuals … trying to equate what they’re doing with a sense of martyrdom.”

Retired brigadier-general Duane Daly, who was instrumental as head of the Royal Canadian Legion with the creation of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier more than 20 years ago, disagreed with those wanting use the site “as a centrepiece for political dissent.”

“That’s a tomb,” he said. “If they want to make a statement like that, go to Parliament. That’s what it’s for, not the tomb.”

Others have suggested some of those using the memorial to amplify grievances against the government actually represent the opposite of the selflessness for which the sites are dedicated.

“The Unknown Soldier died for his country. He died in a selfless act,” said Youri Cormier, executive director of the Conference of Defence Associations Institute think tank.

“When you honk and scream about an idea of personal freedoms that excludes one’s duty to his or her nation, obeyance of the law and … respecting the principle that one’s freedom ends where it infringes on the freedoms of others, it’s putting self before nation.”

It is in this context that some such as the legion and Cormier, who noted that the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Arlington, Va., is defended around the clock by armed military members, have called for greater security at the memorial.

“No one is allowed to usurp or appropriate the sacred ground of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier for some stunt or campaign,” Cormier said. “This sacred space is not for the taking.”

Public Services and Procurement Canada says the site is monitored 24-7, but wouldn’t comment on calls for more security. While the Canadian Armed Forces has a ceremonial guard at the memorial for tourists, Ottawa police are responsible for site security.

The killing of Cpl. Nathan Cirillo by an Islamic State sympathizer in October 2014 prompted a review of security at the memorial, and the eventual placement of military police. But their job is to protect the ceremonial guards while they are on duty.

Exactly what type of security measures should be adopted now isn’t clear.

Most experts agree authorities should not limit or restrict public access to the memorial, partly because the vast majority of visitors to the site are respectful — but also because such a move could play into the hands of some groups.

“In some respects, that’s more dangerous because it feeds into the victim mentality that we’re being silenced, that we’re being oppressed,” said Barbara Perry, director of the Centre of Hate, Bias and Extremism at Ontario Tech University.

Officials erected fences around the memorial at the start of the “Freedom Convoy” after a woman stood on the tomb. But they were later taken down by protesters. Many of them identified themselves as veterans and said they were reclaiming the site — a message repeated as a reason for gathering at the cenotaph during the “Rolling Thunder” event this spring.

Retired lieutenant-general Mike Day also pushed back against the idea of American-style restrictions at the memorial, such as ropes and fences preventing the public from getting close.

“All national monuments need to be accessible. I accept that comes with a cost,” said Day.

“But I think the cost of walling them off and not making them accessible is greater. I accept, therefore, that there will be individuals like we’ve seen who will take advantage of that.”

Lee Berthiaume, The Canadian Press