The public can now use an online interactive tool to check if logging has happened in any B.C. old-growth forest.

Angeline Robertson, project lead for STAND.earth’s new site Forest Eye, says the tool allows the public to see exactly where timber companies have logged in areas the provincial government has designated as old growth.

She said Forest Eye was borne out of frustration.

“What we were struggling with was trying to get information from the government, asking for maps, asking for updated figures, and getting a lot of shaping of those numbers, (telling us that) everything was just fine, that lots of things are being protected.”

In 2020 the B.C. government announced its intention to temporarily defer the cutting of specific areas of old growth until a new province-wide ecosystem-based forest management approach based on the Old Growth Strategic Review is implemented.

Since then the public and the media have not been able to get basic information about areas that were deferred, including the location, size and status of deferral areas. Occasional rumours would surface about old growth that had been logged, but there has been no clear way of fact-checking these.

Forest Eye states that it uses provincial government data and maps, combined with satellite data, remote sensing, and time-lapse video to show where old growth has been logged. The data can be produced two-to-four weeks after the logging is done, Robertson says.

The system observes the overlap between mapped old growth and cutting permits. Then it looks for vegetation loss within that overlap, which indicates logging has taken place. Robertson says the system can distinguish between logging and other disturbances such as wildfire. It also ignores vegetation disturbances that occurred before January 2020.

Indicators like roads and slash piles confirm the presence of logging, and time lapse photography documents the timing and progress of road building and logging.

The tracking system can also identify whether logging roads have been built through old growth, which the government allows even in small old growth stands.

“We’re so keen to watch what happens in environments around the world,” says Robertson. “In this instance, we see logging occurring here, despite all of this work that’s been done to justify deferring it. So I also think that there’s a moment here to say, ‘It’s time to turn the lens on ourselves.’”

She says the satellite surveillance system does not use Google Earth, whose data tends to be out of date, but rather uses information from Planet Labs.

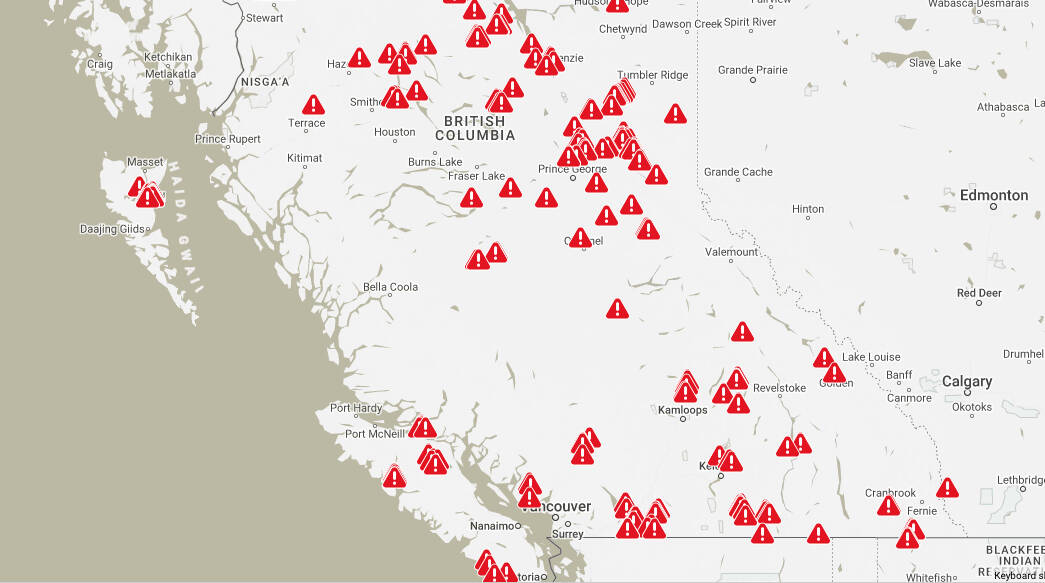

For each incursion of loggers into old growth, the database issues an alert on an interactive map, showing how many hectares of old growth that was cut, the date and location of the cut, and the timber company’s name.

Users of the site can sign up for updates and alerts that will be sent out whenever new logging is confirmed. The site has confirmed 214 alerts so far, and reports that nearly 2,800 hectares of forest slated for deferrals has been logged.

An added problem, she said, was that in 2021 when the deferrals were announced the deferral did not apply if there was already a timber harvesting permit in place.

The Ministry of Forests did not respond to questions from the Nelson Star about the accuracy of the Forest Eye system or why it has not provided a similar tool for the public.

Providing a similar tool is something the province could easily do, says Robertson.

“And they could probably do it way better than us. But they’re not.”

Forest consultant Len Vanderstar of Smithers says he likes the Forest Eye system, even though some of the government information on which it relies may not always be accurate or up to date.

Vanderstar is a retired registered professional forester who worked for 26 years as a biologist for the province.

“I like the product,” Vanderstar says of Forest Eye. “From our knowledge of the land base, it’s fairly accurate. You’re going get anomalies … but that doesn’t mean that the end product is bad.”

Another B.C. forest consultant says the Forest Eye technology “looks accurate and robust.”

Dave Daust, a consultant forester and landscape analyst, said in an email that the tool adds a visual element to the province’s vegetation data, “which is a critical step in such analyses.”

Daust was one of the members of the province’s Technical Advisory Panel, which recommended in 2021 that the province defer 2.6 million ha of at-risk old growth from logging until such time as the province conducted further planning in conjunction with First Nations, and until it revamped its forest management system to better take ecosystem health into account.

Grand Chief Stewart Phillip, president of the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs, praised the STAND.earth database in a July 20 statement.

“Our earth and our trees need more protections because we are losing them at an unacceptable rate due to logging and constant wildfires,” Phillip said. “This tracker is just one way that we can hold corporate greed to account, and we applaud STAND.earth for taking a stand.”

The Forest Eye site states that so far most of the old growth alerts stem from cutting by major logging companies including Canfor, West Fraser, Interfor and Western Forest Products, as well as pipelines including TransCanada’s Coastal Gaslink pipeline.

READ MORE:

• Kootenay forest management ignores old growth protection, two experts say

• B.C. failing to meet promised benchmarks to transform old-growth logging

• Understanding B.C.’s old-growth logging deferrals by the numbers

• Finding the Kootenays’ biggest trees: Biologist mapping the region’s forest giants

bill.metcalfe@nelsonstar.com

Like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter