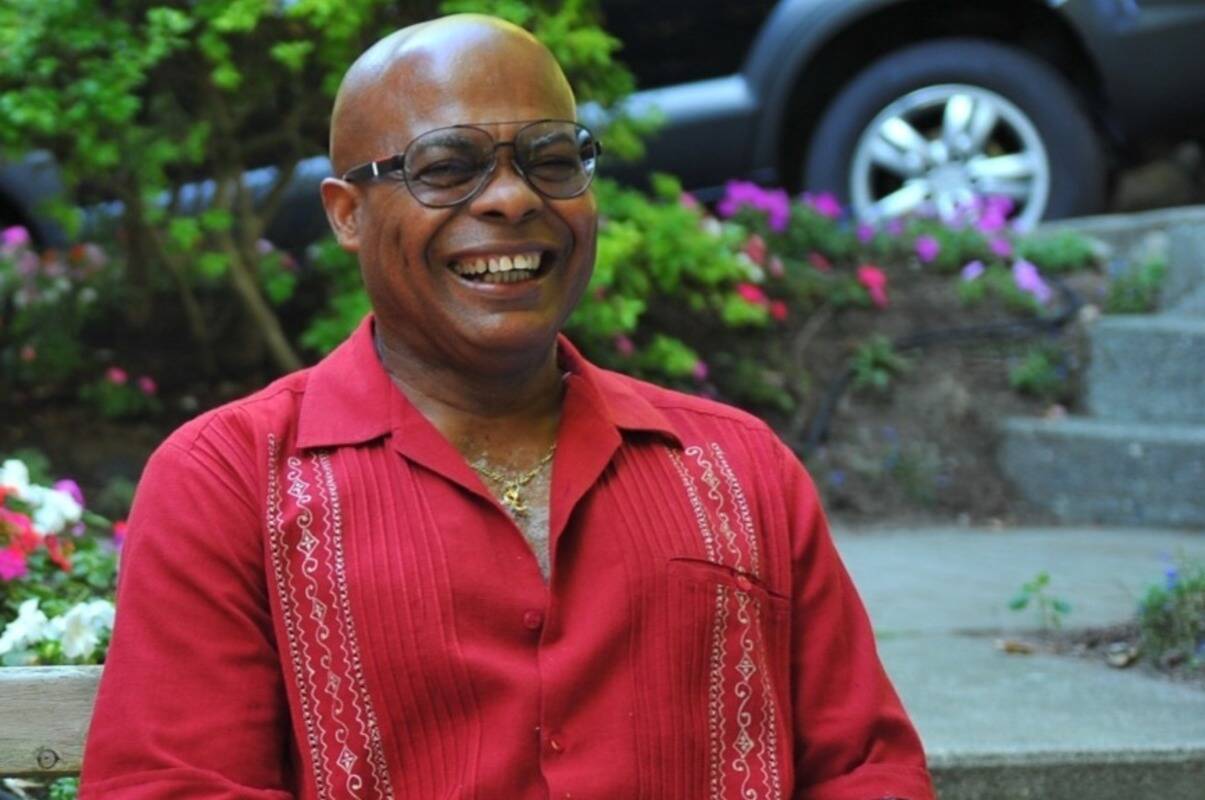

The first Black judge to be appointed to the B.C. provincial court bench and the B.C. Supreme Court has died.

Selwyn Romilly died peacefully at the age of 83 in his Vancouver home on Friday night after a battle with cancer. He was surrounded by loved ones, with his wife by his side.

“My father was a kind and generous man with a wonderful sense of humour,” said Charis Romilly Turner, Romilly’s daughter. “He spent his life dedicated to justice and mentoring others.”

Romilly was born in Trinidad and Tobago in 1940 and moved to Canada in 1960. He attended the Peter A. Allard School of Law at the University of British Columbia and earned a bachelor of arts and law degree just six years after arriving in Canada. He was the fourth Black law student in the history of UBC and the first to graduate. Romilly met his future wife, Lorna, at UBC.

Romilly practiced as a lawyer from 1967 until 1974, working in Kamloops and then Prince Rupert before settling down in Smithers where he and his wife raised two children.

In 1972, Romilly was offered a seat on the provincial court bench but turned down the offer. He was offered the position again two years later and was appointed a judge of the Provincial Court of British Columbia in November 1974, where he served until 1978. He was the first Black person appointed to any court in B.C.

In November 1995, Romilly was appointed to the Supreme Court of British Columbia, becoming the first Black judge to be a part of the Supreme Court. He served as a B.C. Supreme Court Justice until his retirement in 2015.

Smithers lawyer Ian Lawson remembers Romilly as someone who was genuinely interested in people and the community, especially within Smithers.

“Unlike most, but not all, other Supreme Court judges, Justice Romilly was genuinely interested in local counsel and how things are going in the Smithers community,” he said. “He regularly spoke fondly of having a law office here, and often asked about local colourful characters he dealt with — and whether they were still around.”

Lawson goes on to say that Romilly was comfortable during his time in Smithers, and was very thorough and trusted as a judge.

“His comfortable familiarity with Smithers lawyers usually translated into dry witty exchanges between counsel and the bench, which helped to set everyone at ease in his courtroom,” he said. “As a judge, he was known for utter thoroughness in his judgments, particularly in criminal cases. He could be relied on to review all of the cases relevant to an issue, and come to a sound conclusion about them.”

Lawson also recalls discussing footnotes in journal articles by respected professors with Romilly, and how they were often incorrect. Romilly laughed and told him that he noticed the same thing and always did his own research instead of relying on notes from others.

“When I last saw him after his retirement, he offered to send me a copy of his personal bench notes for points of law and procedure in criminal cases,” Lawson recalls. “I have since referred to that document often, knowing there would never be any mistakes in it.”

Two of Romilly’s brothers followed him to Canada, including Valmond, who also worked in the legal profession and eventually became a judge as well.

In May 2021, Selwyn was wrongly detained and handcuffed in Stanley Park by the Vancouver Police Department who was looking for a suspect in his 40s or 50s. Selwyn was 81 at the time.

The department had to make amends for the mistake, but it wasn’t the first time. In fact, it wasn’t even the first time the VPD have had to apologize to a Romilly.

READ MORE: Police apologize after wrongly arresting B.C.’s first Black Supreme Court Justice

Nearly half a century earlier in 1974, Selwyn’s brother, Valmond, was also wrongfully detained and handcuffed, and then falsely imprisoned by Vancouver police officers. Valmond was much taller than the suspect and ultimately won a judgment against the three officers who falsely imprisoned him.

According to Romilly Turner, her father’s reaction to the 2021 incident was to push for reforms in police practices such as racial profiling and searches, and said he never considered suing the department.

Selwyn is survived by his wife, Lorna, and two children, Charis and Jasom.