The Sinixt Confederacy wants the federal government to streamline the U.S.-Canada border crossing for Sinixt people now that they have rights in both countries.

That was just one of many goals discussed at an event in Nelson on April 25-27 entitled Joint Provincial Government/Sinixt Confederacy Ethnohistory Training.

Hundreds of people representing dozens of West Kootenay organizations heard representatives of the Sinixt Confederacy talk about their history, ethnography, the extent of their B.C. territory, and their plans for the future.

Sinixt spokesperson Shelly Boyd said she was surprised by the turnout. It left her no doubt, she said, that there is both curiosity about, and support for, the Sinixt in the West Kootenay.

“The turnout was incredible,” she said, “to see literally hundreds of people walk through those doors. I have a lot of gratitude for this, for the people who showed up both in official capacities and just in the capacity of just wanting to learn. It was very humbling.”

The Sinixt Confederacy is a branch of the Colville Confederated Tribes based in Washington state.

The Nelson event was run three times — two full days and one half-day — for different groups totalling about 520 people. Attendance at the event was by invitation, but the third day was also attended informally by members of the public.

On April 25 about 125 representatives of a dozen federal and provincial government ministries came to the event. The following day the event was attended by about 230 people from 49 organizations and businesses including 13 municipalities, five school districts, two chambers of commerce, six timber companies, two Community Futures organizations, three museums, two regional districts, two community forests, and three hydro producers.

On April 27 about 170 people from 58 environmental, cultural, recreational, tourism, scientific and business groups attended the half-day session.

Ethnography and history

One of the purposes of the meeting was to present a new report from the Attorney General of B.C. entitled Sinixt Traditional Territory: A Review of Ethnographic and Historical Sources.

The report summarizes ethnographic information relating to the traditional territory of the Sinixt people. The 240-page document is mainly about the Sinixt but also about the presence of others who accessed Sinixt territory in the 19th century such as neighbouring Indigenous groups, government officials and settlers.

At the April 27 session, local historian Eileen Delehanty Pearkes gave a slide presentation that summarized the report.

She showed maps of Sinixt villages and hunting trails that existed between the time of contact with Europeans (1811) and the date that the U.S. and Britain first divided the territory (1846).

This information, she explained, was obtained by the province and historians from records left by explorers, traders, surveyors, mapmakers, missionaries and ethnographers who reported on their sightings of, and contacts with, Sinixt people.

She described these as primary sources, “not secondary sources, not local histories, not memoirs, not ‘this is what it was like when I was a kid growing up.’ Those kinds of secondary sources have sometimes erroneously left out the Sinixt. The primary sources are the people who actually knew them, saw them, or spoke with them directly.”

For example, from the summary introduction to the report:

“Ethnographer James Teit recorded the location of 20 Lakes (Sinixt) villages in British Columbia located on the Upper and Lower Arrow lakes, Slocan Lake, Trout Lake and the Lower Kootenay and Slocan rivers. Shortly after Teit’s publication, ethnographer Verne Ray located and mapped the presence of 30 Lakes villages north of the border and 10 in Washington State. Anthropologist William Elmendorf also worked with Lakes consultants, documenting in great detail information regarding Lakes territory, culture, and people.”

The report elaborates extensively on the travels and observations of these men and others, including maps of villages and trade routes.

Following Pearkes’ summary, Boyd presented stories, observations, and photos about Sinixt history from a community point of view.

“We didn’t want the report to just be about history,” she said. “We wanted to talk about our voices, the way we saw our history, the way we felt, the way we experienced it. This is not just about reports about us. It’s real lives.”

After the court case

Another reason for the Nelson event was to give an update on the aftermath of R v. Desautel, the Supreme Court of Canada case that in 2021 declared the Sinixt an aboriginal people of Canada under the constitution, with hunting and related rights in Canada.

Cindy Marchand explained that cultural anthropologist Andrea Laforet researched and gave evidence to the court on the genealogies of the Sinixt families that could be identified as living in B.C. at the time of contact with Europeans (Laforet determined there were 21 such families.) She also researched whereabouts of those families now, and whether Rick Desautel was descended from one of them (she decided he was).

Marchand said Laforet is now doing further genealogical work to identify Sinixt people who don’t live at Colville.

“We recognize that we’re not the only Sinixt people. We do want to recognize that Sinixt descendants exist with other tribes on both sides of the border. They exist all over.”

Marchand said they are doing this to offer all Sinixt the opportunity to join one governing body “to make decisions on how they would like to govern themselves.”

She said the Sinixt Confederacy is also working at getting more recognition from the federal government and this will take some time because it involves not only the willingness of the government but also the differences in governance systems between the U.S. and Canada, as well as other legal subtleties.

“If this is confusing for you, it’s confusing for us too,” she said.

Marchand said two things the Sinixt hope to achieve at the federal government level is a streamlined process for crossing the border and inclusion in all federal and provincial funding sources.

Maps and recognition

A third reason for the meeting was for the Sinixt office in Nelson, opened in October, to give an update on its activities and plans.

James Baxter, a biologist who runs the Nelson office said they have been building relationships with a variety of companies, ministries and community organizations, getting started on such issues as old growth forests, white sturgeon water management, mountain caribou recovery, and salmon recovery.

Until the Desautel decision, the Sinixt were not on the provincial government’s radar because they had been declared extinct in Canada by the federal government in 1956. They were not consulted when ministries and industries carried out their required engagements with First Nations that would be affected by their work.

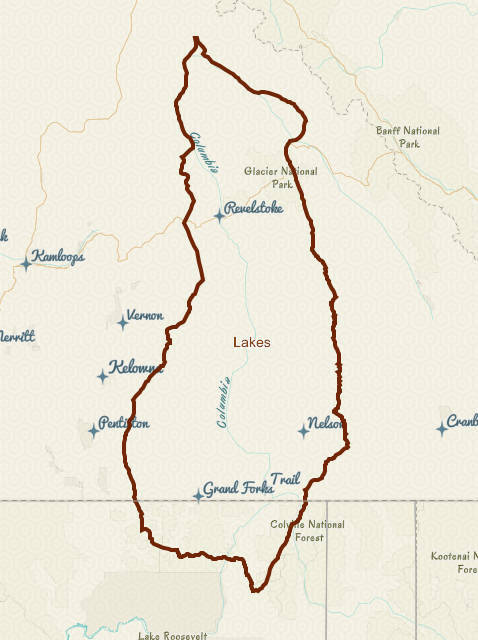

Now there is confusion as to when consultation is needed, Baxter said, and uncertainty about the geographic boundaries of Sinixt traditional territory.

He said the province’s Consultative Areas Database in its online public version does not include the Sinixt, but in the version government workers can access, the Sinixt territory does appear.

It’s a priority, Baxter said, to get an updated traditional territory map available to everyone, and to raise awareness of this confusion and of the boundaries of the territory. He said raising awareness of this issue was one of the reasons for the event.

READ MORE:

• Sinixt Confederacy opens office in Nelson

• Sinixt Confederacy asks B.C. for formal assessment of proposed Zincton resort

• Sinixt cry foul over Columbia River Treaty funding given to other Indigenous groups

• Agreement reached to share Columbia River Treaty revenues with First Nations

• ‘We’re still here’: Sinixt return to Nelson to celebrate anniversary of Supreme Court victory

• PHOTOS: Sinixt visit Nelson during canoe tour