Provincial officials in Saskatchewan and Alberta got a Valentine’s Day surprise from the prime minister this year when he called to say he was considering invoking the Emergencies Act, a public inquiry heard Thursday.

Lawyers representing the two provinces were before the Public Order Emergency Commission, which is looking into the federal government’s use of emergency powers to end to weeks of protests at border crossings and in downtown Ottawa.

“The call (on Feb. 14) was not so much about consulting, it was about telling,” said Saskatchewan government lawyer Mike Morris.

“That phone call was the first time the federal government told the government of Saskatchewan that it was considering invoking the Emergencies Act and declaring a public order emergency.”

The Liberal government invoked the Emergencies Act on Feb. 14, the first time the law had been used since it replaced the War Measures Act in 1988. The move temporarily granted police extraordinary powers and allowed banks to freeze accounts.

Saskatchewan and Alberta say they objected to its use and believe the law did not need to be applied across the country.

Alberta’s lawyer, Mandy England, described in her opening statement before the commission how existing laws and police resources successfully ended a protest at the border in Coutts, Alta., where several people were arrested and charged with conspiring to commit murder after a cache of guns, body armour and ammunition was found in nearby trailers.

“None of the powers that were created under the federal Emergencies Act were necessary, nor were any of them used in Alberta to resolve the Coutts blockade,” she said.

The federal government is planning to argue the opposite. Robert MacKinnon, representing Justice Canada, said the Emergencies Act was “reasonable and necessary” given the circumstances across the country.

“The evidence of the government witnesses will detail the facts and events leading to the decision to declare a public order emergency,” he said.

That decision came after weeks of what Trudeau called an “illegal occupation” of downtown Ottawa, and tales of frustration from people living in the area, many of whom were critical of the police response.

Peter Sloly resigned as Ottawa’s police chief in the midst of mounting public pressure during the protests. His lawyer, Tom Curry, said the former top cop has a list of recommendations to prevent, alleviate, respond to and recover from significant protest events.

David Migicovsky, legal counsel for the Ottawa Police Service, said there were well-established processes in place to deal with protesters, but they didn’t work during the “Freedom Convoy.”

“The police had little time to prepare. The genesis of the protest only began a few weeks before it arrived,” he said, adding it was difficult to gauge the size of the convoy because many people joined as it moved closer to Ottawa.

“That could not have been predicted.”

He said none of the intelligence reports predicted the “level of community violence and social trauma that was inflicted on the city and its residents.”

A lawyer representing the Ontario Provincial Police said they will show how intelligence was gathered, including through a liaison team with protesters, and shared with policing partners.

The Public Order Emergency Commission was established on April 25, and has been collecting documents and interviewing dozens of people. Six weeks of public hearings in Ottawa are planned.

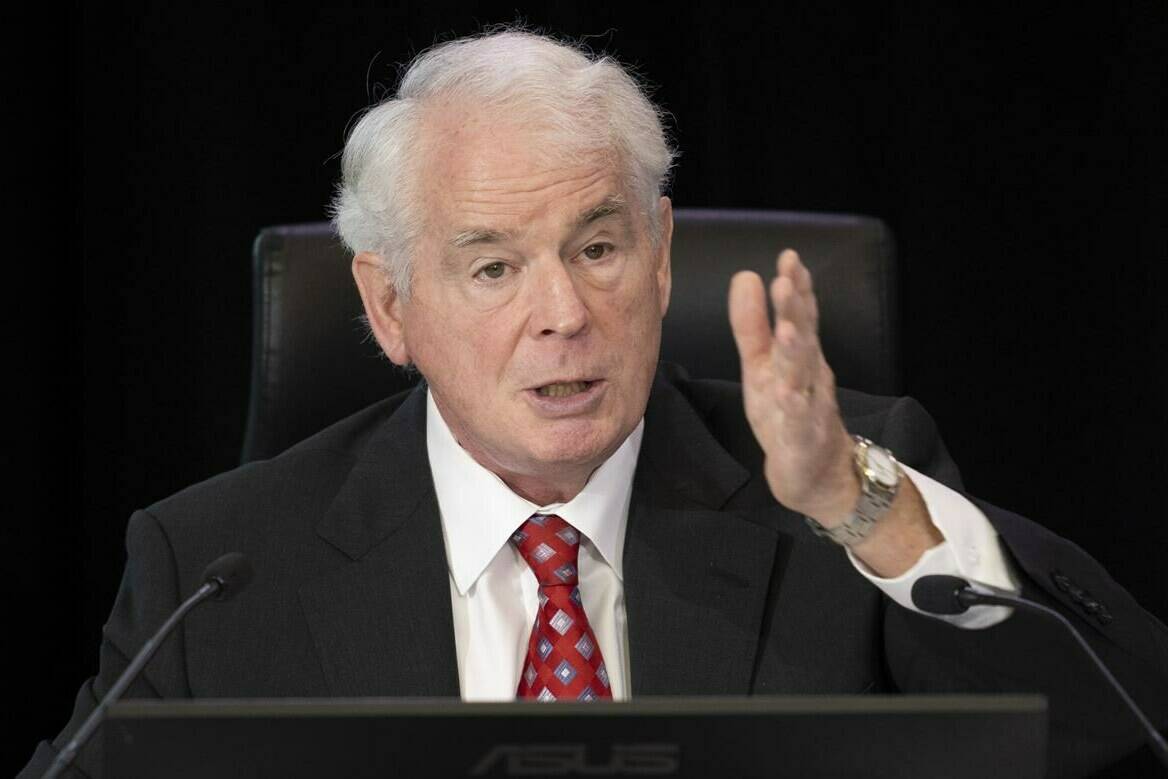

“Uncovering the truth is an important goal,” the commissioner, Ontario Court of Appeal Justice Paul Rouleau, said in his opening remarks.

“When difficult events occur that impact the lives of Canadians, the public has a right to know what happened.”

Rouleau said the process of getting to the start of the inquiry has been “challenging.”

“Discharging my mandate is not an easy task,” he said, later adding that “timelines will be tight.”

He appealed to participants and their legal counsel to co-operate to ensure the facts are properly presented to the public, and said inquiries are meant to learn from experience and make recommendations for the future.

“They do not make findings of criminal liability, they do not determine if individuals have committed a crime.”

Witnesses will begin testifying on Friday, a list of 65 people that includes Trudeau, seven other cabinet members, police forces, and officials from all levels of government.

The commission will also hear from central figures in the “Freedom Convoy” such as Tamara Lich, Chris Barber, Pat King and James Bauder — all of whom are facing criminal charges for their roles.

Lich was among those in the public viewing gallery Thursday.

“I’m really happy to be back here and I’m looking forward to testifying,” she said in one of her first public statements since being arrested for her role in the convoy.

A lawyer representing “Freedom Convoy” organizers told the inquiry they will argue there was no evidence the law was necessary to end the protests that took over streets around Parliament Hill last winter.

“There was no reasonable and probable grounds to invoke the Emergencies Act and the government exceeded their jurisdiction, both constitutionally and legislatively, in doing so,” said Brendan Miller.

Commission counsel presented reports Thursday that describe dozens of protests mounted against COVID-19 public health measures and lockdowns across Canada, starting in the spring of 2020 and culminating in the convoy to Ottawa.

Police took action in many of those demonstrations, and arrested or ticketed protesters who were part of crowds of varying sizes over the two years the pandemic dragged on.

The City of Ottawa’s auditor general has also launched a review of the local response to the convoy, and several groups have initiated proceedings in Federal Court to challenge the government’s use of the Emergencies Act.

The inquiry is also distinct from the all-party parliamentary committee struck in March to review the Emergencies Act’s use.

Both the public inquiry and the parliamentary committee, which continues its work, are required under the Emergencies Act.

—David Fraser, The Canadian Press

RELATED: 5 things to know as the Emergencies Act public inquiry gets underway