In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, lawyers for homeless residents of Vancouver’s port lands asked Stepan Wood to research how jurisdictions were dealing with encampments amid the public health crisis.

The University of British Columbia law professor’s team then compiled his findings in an affidavit.

The legal document showed public health agencies across North America were saying breaking up encampments was a bad idea and a better approach was to work with residents to ensure they physically distanced and took sanitary measures.

But the affidavit had no impact and wasn’t referenced in the decision that granted an injunction against the homeless.

“The court decision was really remarkable in terms of reaching a new level of hostility toward encampments,” Wood said in an interview, adding the plaintiff’s claims were being accepted at face value.

The case made him interested in how the courts treat encampment injunctions and he soon found the topic had never been explored in depth. It’s what inspired his new report titled Rush to Judgement, which analyzes injunctions against homeless encampments on public property in B.C. between 2000 and 2022.

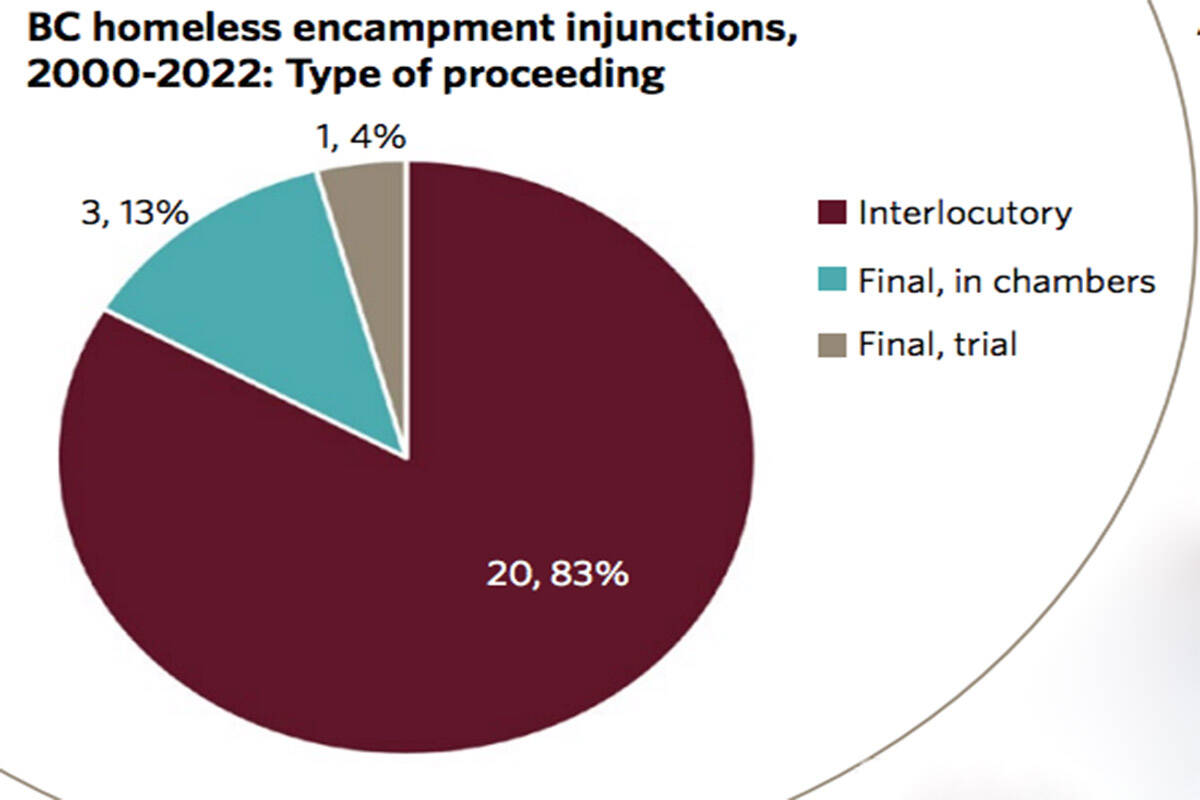

It found that the court supported 85 per cent of government applicants who sought an interlocutory injunction – an interim order granted at the start of a case that would break up encampments in this context.

In Victoria, those injunctions were granted four of the five times they were sought since 2000.

Wood calls it an “alarming” trend as interlocutory injunctions are meant for extraordinary circumstances, given how the order is made before claims can be proven in court.

“This report reveals that in homeless encampment cases, interlocutory injunctions are the norm, not the exception,” the report states.

Wood sees many issues with interlocutory requests when it comes to encampments. It’s hard for homeless residents to organize evidence, or find lawyers willing to work pro bono, before the case is initially heard, Wood said. Then if people are dispersed from the encampment, it can be difficult for lawyers to stay in contact with them.

Interlocutory orders usually mark an end to the proceedings since the goal is to disperse encampments, so Wood said governments are getting what they want before cases are even tried.

“It shows that the courts are really too eager to oblige governments when they come asking for injunctions against homeless encampments,” he said.

“If the courts start to stand up and refuse these interlocutory injunctions, that should put pressure on governments to deal with the underlying issues rather than kicking the ball down the road.”

Only four out of 24 cases saw final injunctions – ones granted if the government proves its case – considered by the courts during the 22-year period. Two final injunctions were denied, one was adjourned and one in Saanich was granted.

The Saanich encampment lawyers didn’t contest it as those residents had already been evicted by an interlocutory order.

“The court was really unsympathetic to the encampment residents and really took the government’s position hook, line and sinker in the absence of really significant evidence that this encampment was harmful,” Wood said of the Saanich case.

As the report points out, applications for permanent injunctions had a zero per cent success rate when they were contested.

Wood said it shows that when vital interests and rights are given more attention, the courts tend to favour encampment residents.

As the injunctions deal with the people’s health, safety and survival, Wood said the courts should consider the harms of evicting residents, and if dispersing them to streets and alleyways will lead to worse outcomes for everyone. His report notes encampments – compared to the streets – have been shown to lower the risk of violence, theft and toxic drug overdose deaths, while they’ve also been tied to improved health.

Wood said governments will emphasize fire risks, crime and drug use to justify court action, but he argued encampments make those issues more visible, not more common.

“There’s not convincing evidence that encampments actually increase these problems.”

The Supreme Court of Canada has since 2018 required petitioners to meet a significantly higher standard in relation to homeless encampment injunctions, but Wood said not a single B.C. court has applied those legal tests.

“That baffled me because it’s very clear from the Supreme Court of Canada that they have to, but they haven’t.”

Past rulings have found it unconstitutional to deny overnight sheltering on public lands when there isn’t “reasonably available alternative shelter.”

B.C. on Nov. 6 introduced amendments to that “alternative shelter” definition to make it “a staffed place where an individual may stay overnight, and have access, either at, or nearby the shelter to a bathroom, a shower, and an offered meal.”

The move was meant to provide clarity and guidance to municipalities who are seeking injunctions, according to the province.

“The lack of a standard for suitable shelter has both hurt people who have been decamped without proper shelter and created barriers to resolving encampments. It’s not working for anyone,” Housing Minister Ravi Kahlon said in a statement.

Wood called the update “extremely regressive” because while those shelter spaces will still be inaccessible to many experiencing homelessness, the language means courts would have to consider them available and therefore grant an injunction.

“It basically says the courts, when considering these injunctions, have to ignore all of these factors that they have already recognized are essential to decide whether an injunction is justified and whether these people’s constitutional rights would be infringed,” the law professor said.

The amendment also means a person’s shelter need has been met if there’s an overnight bed available, but Wood said courts in Ontario have recently recognized people also have a right to daytime sheltering.

“It’s really dialling the clock back to where we were more than ten years ago in terms of the understanding of the law.”