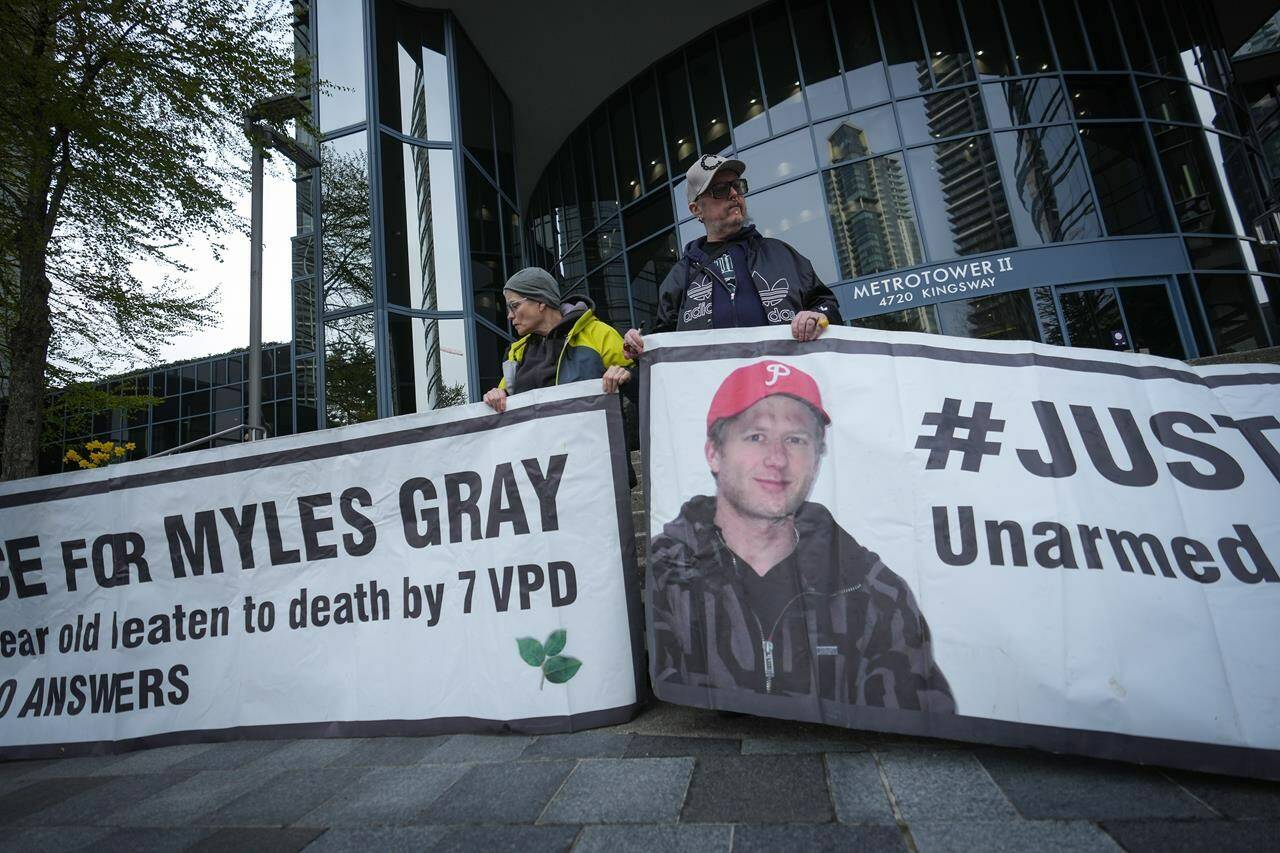

A Vancouver police constable told a coroner’s inquest that “time was standing still” as he waited for advanced life support paramedics to arrive and help revive 33-year-old Myles Gray after he was beaten by officers trying to arrest him.

Const. Derek Cain described to the jury Friday of their efforts to resuscitate Gray, who stopped breathing twice in the moments after police handcuffed him.

Cain said he arrived in the yard where police were struggling to subdue Gray in response to a call for backup on the day the man died in August 2015.

Gray had been in Vancouver making a delivery to a florists’ supply shop for the business he operated on the Sunshine Coast, and the inquest has heard the initial 911 call was about an agitated man who sprayed a woman with a garden hose.

The beating left Gray with injuries including a fractured eye socket, nose and rib, a crushed voice box and ruptured testicles.

Cain testified that Gray was sweating profusely, he wasn’t communicating normally, and he displayed “superhuman” strength that left the officer in “disbelief.”

Gray’s symptoms suggested the officers weren’t dealing with someone who simply didn’t want to be arrested, said Cain, who had previously worked as a paramedic.

The officer said he assessed the situation as “excited delirium,” describing it as a life-threatening medical emergency that required immediate intervention.

It wasn’t an option to let Gray walk away, he told the jury in Burnaby, B.C.

Earlier this week, Coroner Larry Marzinzik provided the jury with what he called a “cautionary note” about the term excited delirium.

To his knowledge, Marzinzik said it’s not recognized as a cause of death by most pathologists. The jury members should put less weight on the evidence of a lay person on the topic and would be hearing from a medical expert later, he said.

A statement from the BC Coroners Service said it no longer recognizes excited delirium as a cause of death in its investigations, saying the decision “was made in response to the evidence-based literature changing over time.”

The position aligns with that of the World Health Organization, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, and others who agree it’s “not a diagnosis (or) cause of death but more of a conglomeration of signs and symptoms,” it said.

With Gray in handcuffs, Cain said he called for advanced life support paramedics, who are specially trained and carry equipment required to administer sedatives.

Cain’s communication with Gray changed from telling him he was under arrest to saying help was on the way, the officer said.

“I made numerous requests over the radio,” Cain said. “I asked for a supervisor to go to the hospital and pick up one (advanced life support) paramedic with his drug kit and come and help. It’s the only thing that could have helped.”

Then, Gray let out a deep sign and stopped breathing, Cain said.

He said he moved Gray into a sitting position and rubbed his sternum. Within a few seconds, he said Gray started breathing and tensing his muscles again.

But Gray stopped breathing moments later, and efforts to revive him through chest compressions, oxygen and an automated defibrillator were not successful.

“I truly believed in all my heart that we would bring him back,” Cain told the inquest.

“I’ve had nightmares about this call for seven-and-a-half years,” he said.

Cain also told the inquest on Friday that a police union representative told him not to make handwritten notes after the incident, echoing earlier testimony the jury heard from two other officers.

Several additional Vancouver police officers are expected to testify at the inquest that began Monday with testimony from Gray’s sister, Melissa Gray.

She described her brother as goofy and kind, saying he’d been diagnosed with bipolar disorder in high school, around 1999, but he’d been stable ever since.

The coroner’s jury won’t be able to make findings of legal responsibility but may make recommendations to prevent similar deaths in the future.

The BC Prosecution Service announced in 2020 that charges would not be approved against the officers, saying police were the only witnesses to the incident and the Crown couldn’t prove any offence had been committed.

—Brenna Owen, The Canadian Press

READ MORE: Officers told not to make handwritten notes after death of Myles Gray, inquest hears

READ MORE: Eight years on, inquest into police-linked death of Myles Gray to begin in Burnaby