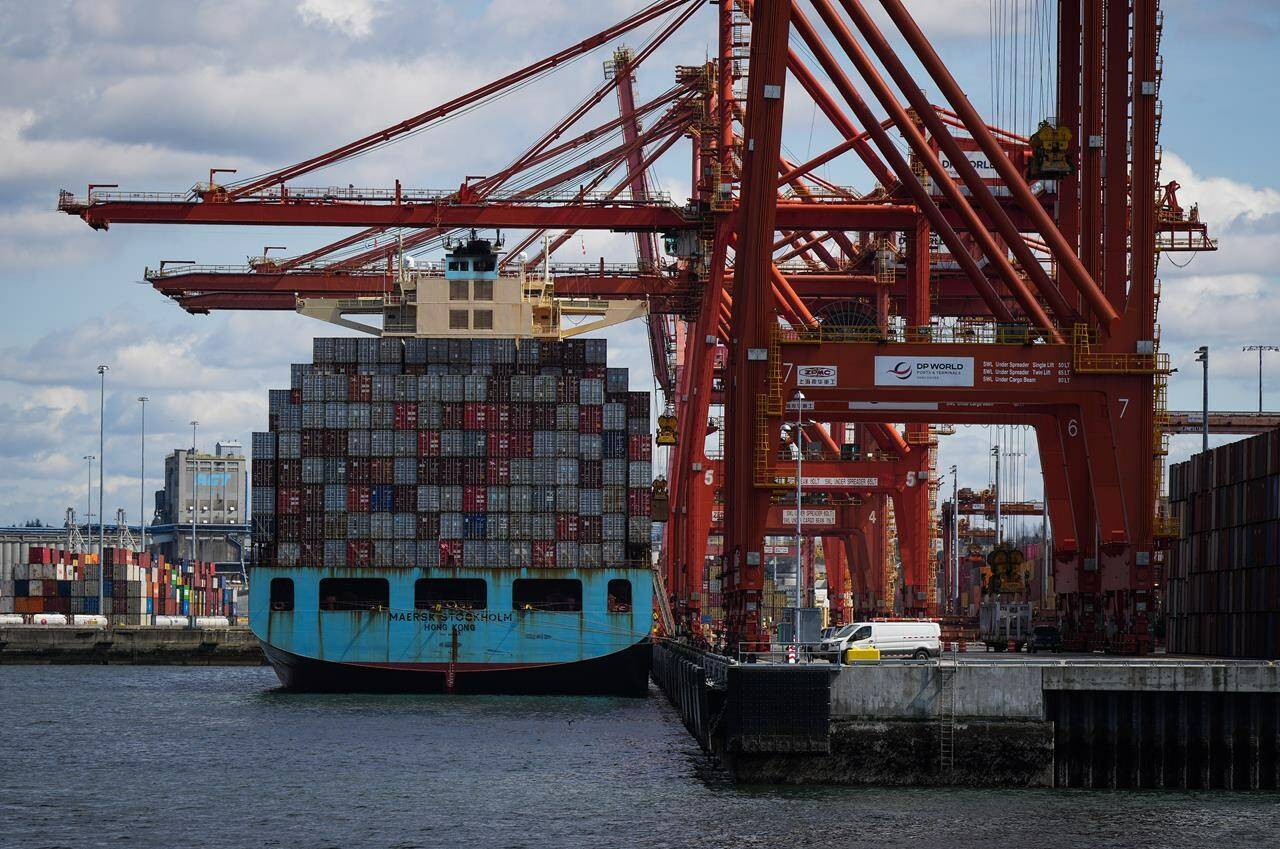

Cargo volumes at Canada’s largest port fell by three per cent last year as the global economy began to show signs of a slowdown.

Though grain and fertilizer exports surged in the second half of 2022, the gains were not enough to offset a sputtering start to the year caused by a weak 2021 harvest and lingering supply chain problems, the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority said Monday.

After more than a year of rising container traffic, imports also fell by four per cent amid softer consumer demand and overstocked inventories, port authority CEO Robin Silvester said in a phone interview.

Despite the decrease, he stressed that more capacity is “desperately needed” due to rising trade and population forecasts down the line. A new container terminal that would boost that capacity by nearly 50 per cent, dubbed the Roberts Bank Terminal 2 Project, received federal cabinet approval last month — a critical step — but still requires various permits to proceed.

A green light from the Department of Fisheries and Oceans is expected to take at least a year, he said, with permits also needed from B.C.’s Environmental Assessment Office.

Cruises were one area to come roaring back after a two-year hiatus, with a record 307 vessels dropping anchor in Vancouver — though the number of passengers still fell 24 per cent below 2019 levels.

The wave of cruise ships shows no signs of ebbing, Silvester said from his waterfront office, where the Grand Princess, Koningsdam and Norwegian Jewel were visible through the window. Meanwhile a bumper crop in 2022 along with sharply reduced grain supply out Russia and Belarus — fallout from the former’s invasion of Ukraine — point to increased grain shipments this year.

But container traffic in Canada has continued to drop off as Canadians tighten budgets amid higher interest rates and ongoing inflation.

In March, container volumes across the country dropped nearly 12 per cent year over year, according to the National Bank of Canada.

“We still have softer consumer spending. And we’re certainly also hearing about congestion in the supply chain with full warehouses in the main population areas around Toronto and Montreal, stock not clearing through the system as quickly as normal,” Silvester said.

Sluggish movement of the corrugated steel boxes reflects lagging economic output — preliminary figures from Statistics Canada suggest the economy contracted by 0.1 per cent in March.

“Container trade normally tracks pretty closely with GDP. So when we’re seeing GDP down, then we expect to see container trade down,” Silvester said.

Nonetheless, the port handled its second-highest annual volume of containers on record last year, he noted — though 28 per cent of them were empty, compared with 18 per cent in 2020. The higher proportion owed to lower grain exports and higher freight rates, the port said.

Meanwhile, a 12-day strike by more than 150,000 federal public servants — now over for the vast majority after a tentative deal was announced — has already started to dent container cargo, Silvester said.

“Shipping lines are always nervous about the risk of having containers stuck behind the picket line,” he said.

In spite of ongoing supply chain hurdles and a stalling economy, Silvester highlighted bright spots on the near-term horizon.

“At this stage, 2023 is set to be a strong year with very strong grain volumes with the recovery from the drought in 2021,” he said, adding that potash and steelmaking coal traffic remain hot commodities.

—Christopher Reynolds, The Canadian Press

READ MORE: Ottawa cites jobs, capacity, approves B.C.’s Roberts Bank Terminal 2 port expansion

READ MORE: Transport Canada rejects ban on freighter anchorages off of Vancouver Island