Warmer weather and fading fears about COVID-19 have immigration experts warning of more irregular efforts to cross the Canada-U.S. border — and not only in one direction.

While Canada has for years been a destination for desperate asylum seekers who avoid official entry points in hopes of staking a refugee claim, anecdotal evidence suggests U.S. border guards are encountering more people who are headed the other way.

The latest incident came late last month, when six Indian nationals were rescued from a sinking boat in the St. Regis River, which runs through Akwesasne Mohawk territory that extends into southeastern Ontario, southwestern Quebec and northern New York state.

A seventh person, spotted leaving the vessel and wading ashore, was later identified as a U.S. citizen. Brian Lazore is now in custody in what U.S. Customs and Border Protection officials are characterizing as a human smuggling incident.

Court documents say Lazore specifically asked the six people on the boat, which had no life vests or water safety equipment, whether they could swim. All six replied, “No swim,” the documents say.

It’s the second high-profile incident involving Indian nationals in recent months. In January, a family of four died of exposure in blizzard-like conditions in Manitoba, just metres from the Canada-U.S. border, as part of what officials in Minnesota have alleged was a similar human smuggling effort.

Border guards and experts alike say that after nearly two years of rigid travel restrictions and strict health-policy enforcement, illegal and irregular migration is beginning to ramp back up towards pre-pandemic levels.

Border authorities in Maine have also recently encountered carloads of illegal migrants, including five Romanian nationals who entered last month from Canada and had no legal right to be in the U.S., where concerns about illegal migration at the southern border captures daily headlines.

Customs and Border Protection did not respond to media questions about two other April incidents involving a total of 22 people, including 14 from Mexico and seven from Ecuador, including which direction they were travelling when they were stopped.

Chief Patrol Agent William Maddocks, who oversees that sector, said in a statement that border officials have seen a “notable increase of foreign nationals with criminal history” in the area in recent weeks.

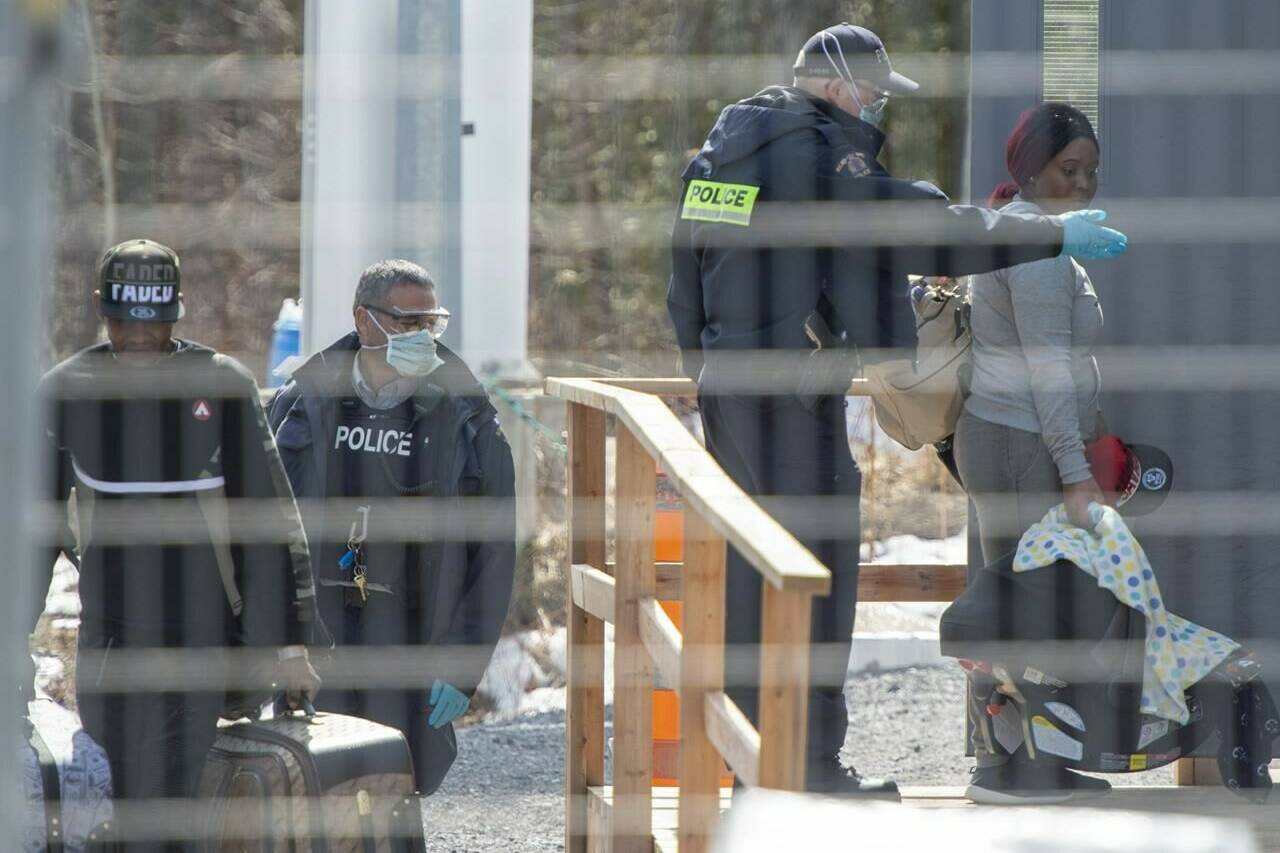

In Canada, there’s already evidence of a significant increase in the flow of migrants to Roxham Road, a spot near the border town of Hemmingford, Que., that in recent years has become arguably Canada’s most popular unofficial border crossing.

Streams of people, as many as 5,700 in August 2017 alone, would make their way to the junction, where the Safe Third Country Agreement — a Canada-U.S. treaty that turns around would-be refugees who try to make a claim at an official crossing — doesn’t currently apply.

Canada eased its own pandemic-related immigration restrictions late last year, and the number of asylum seekers at the border has increased in turn since then.

Police intercepted more than 7,000 people entering Canada between official entry points in December 2021 and January and February of this year, almost entirely in Quebec — a frigid stretch when irregular migration is normally at its lowest ebb. Prior to the pandemic in 2019, RCMP reported only about 2,700 interceptions for those same months.

“We weren’t particularly surprised with those numbers, because we had heard lots of stories,” said Frances Ravensbergen, a resident of Hemmingford who helps to co-ordinate the efforts of Bridges Not Borders, an outreach group for migrants in the area.

Experts say the quieter days brought on by COVID-19 are likely at an end.

“I think we’ll see a return to pre-pandemic levels as travel restrictions ease across the globe,” said Sharry Aiken, a law professor at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont., who specializes in immigration policy.

Even though the threat of COVID-19 has by no means retreated, the trend around the world has been to ease restrictions at the border for both travellers who are crossing legally and for those seeking to claim asylum, Aiken said.

“To the extent that it’s now easier for people to leave their own countries and travel through other countries, it’s reasonable to assume that the pre-pandemic numbers in relation to traffic across our shared northern border will return.”

As for whether the U.S. needs to brace for a significant increase of illegal migration from Canada, Aiken said any such spike would surely pale in comparison with the challenge border security and immigration officials face at the southwest border.

“This problem … is not necessarily coming to public attention, and one can assume that some of it is going on without ever coming to public attention,” she said. “But it’s still not a logical leap to assume that the traffic into the U.S. is anything resembling a steady flow. And I suspect it’s much more an aberration than the norm.”

The immigration picture in the U.S. has been dominated since the onset of COVID-19 in March 2020 by Title 42, the 1940s-era regulation invoked by former president Donald Trump that allows health authorities to turn away migrants if they are deemed a potential health threat.

President Joe Biden has already announced plans to end Title 42 later this month, though it’s not clear whether that will happen on schedule given concerns in Congress and in the courts about the risk of a fresh surge of irregular migration.

The numbers at the northern border suggest an increase is already underway.

In March alone, U.S. Customs and Border Protection reported 7,813 encounters — people deemed inadmissible due to their immigration status or under Title 42 — at or near the Canada-U.S. border, compared with just 1,989 in the same month of 2021.

The pandemic also interrupted a trend that had largely gone unnoticed in the years prior: a steady increase in the number of people apprehended near the northern border after entering the U.S. illegally from Canada.

U.S. Border Patrol officials working in the eight northern sectors made just 2,283 apprehensions during the fiscal year 2016 — a total that reached just over 4,400 apprehensions for the 12 months of fiscal 2019 before the onset of the pandemic in March 2020.

—James McCarten, The Canadian Press

RELATED: Winter weather, vast expanse make patrolling Canada-U.S. border a daunting challenge