By Rachel Morgan, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter, The Pointer

We are living through unprecedented times.

That was the tagline when the startling COVID-19 pandemic swept across the globe.

But the phrase had already become commonplace for a generation altered by the reality of climate change. What scientists now commonly call the “sixth extinction event”, defined by the massive loss of plant and animal life over a short geological period, is the likely outcome of temperature increase caused by human activity, namely the use of carbon to create the addictive energy that fuels our lifestyles.

But we are also, simultaneously, living through unprecedented technological times. We now have, more than ever before, the science to solve some of the world’s greatest problems.

Last month, physicists delivered perhaps the most significant experimental result, ever. It holds the promise of bringing Star Trek to life.

READ ALSO: Fusion breakthrough a milestone for climate, clean energy

But experts are already warning that `nuclear fusion’ technology, suddenly being heralded by many as the panacea, the great answer to our planetary climate problem, should not distract from the critical role renewable energy sources are already playing in our quest to cleanse Earth.

While some forms of renewable energy have been used as far back as 2,000 years ago when the Greeks built water mills to turn grains into flour, modern renewable energy technologies first began to take shape over the 19th and 20th centuries. It wasn’t until the turn of the 21st century that technologies like wind turbines and solar panels reached the point of viability as wide scale sources of energy. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), renewable sources of energy are now, collectively, on track to surpass coal as the number one generator of electricity by 2025.

A month ago, everything changed. Suddenly, the entire conversation around alternative energy has been shifted, forever.

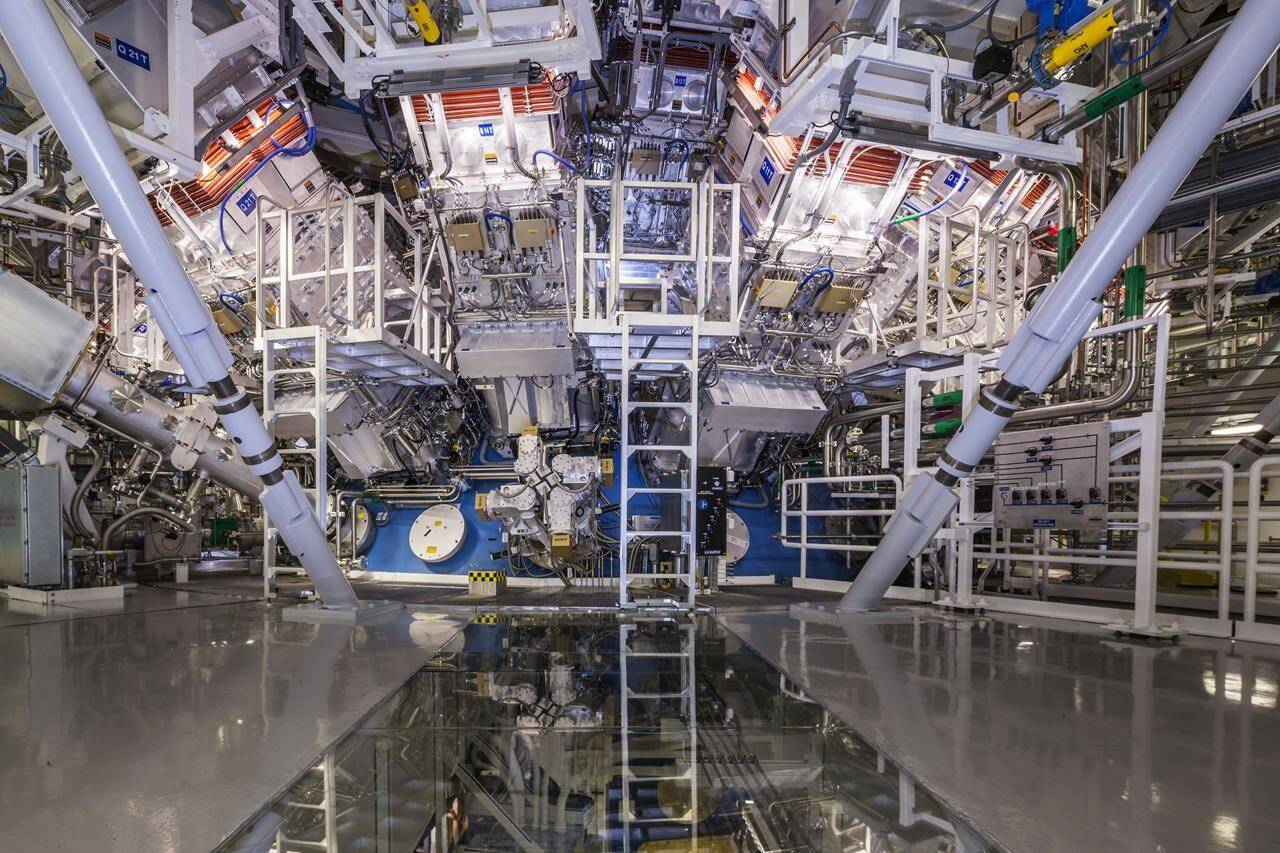

On December 5, at the National Ignition Facility (NIF), part of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California, 192 lasers were directed at a miniscule, frozen pellet of deuterium and tritium, heavier forms of hydrogen. Combined, the lasers fired 2.05 megajoules of energy generating enough heat and pressure to cause the hydrogen inside to fuse. While the tiny blaze only lasted a billionth of a second, creating temperatures roughly ten-times hotter than the sun, the impact was everlasting. For the first time, the output of energy from the reaction was greater than the input, almost 50 percent greater.

The process, called nuclear fusion, is the reaction that powers the sun. While it was discovered back in the 1930s that this process was possible to replicate, NIF is the first to have achieved “ignition”, a net gain of energy.

When news broke there was a sigh of relief across the globe. Immediately, articles began circulating about salvation for the planet as fusion would, inevitably, power a clean energy grid.

But as the novelty of the remarkable breakthrough begins to wear off, researchers and scientists are already wary of the potential negative consequences.

“I was not overly optimistic,” Jean-Thomas Bernard, a visiting professor in the Department of Economics and the Institute of the Environment at the University of Ottawa, says. His expertise deals with the economics of energy use and he addressed the potential of nuclear fusion. “It is a good idea to proceed with developing, doing research on that line. But we are very far from seeing commercial plants being built.”

His concern, like many others in the growing fields dedicated to finding solutions for the most pressing environmental issues, is the danger of being distracted by a silver bullet, especially one that might arrive too late.

It could take more than 40 years before nuclear fusion can be harnessed and scaled to create the amount of electricity needed to change the game. Meanwhile, alternatives that are already doing this, could be suddenly overlooked, in favour of a technology that won’t be ready before catastrophic climate change alters Earth, forever.

Currently, there is research and testing into two different methods to create the type of nuclear fusion the California experiment produced. Both rely on heavy forms of hydrogen which are compressed until they fuse together emitting energy that can create steam to turn a turbine. The process used at the NIF lab relied on laser beams directed at the elements, which needed about 99 percent more energy to actually operate them than what was ultimately produced (the ignition event only measures the energy gain from the laser output, not the electricity required to run the laser machines).

Another process being experimented with across the globe, including in British Columbia, uses magnetic force to create the pressure and heat needed for the elements to fuse. It is unclear which process will result in the biggest gains, using the least amount of initial energy input. It’s also unclear which of the two methods might be realistically scalable, to use for global electricity production. Scientists have also said it is hard to predict how long it will take to advance current technology around each method to the point when nuclear fusion can be widely generated to create energy for everyday human use.

Experts agree it could still be decades before we see fusion contributing to our electricity grid.

Claudio Canizares, an engineering professor and executive director of the Waterloo Institute for Sustainable Energy at the University of Waterloo, says he is not fully convinced fusion will take over as the sole provider of electricity in the future.

“It’s a bit premature to say that, because batteries, solar, wind, renewables in general will improve their performance and cost as well. Our main concern at this point is we don’t want a continuance of greenhouse gas emissions. From that perspective, I think all of these technologies .125renewables, batteries, fission and fusion.375 have something to offer.”

One fear is the nuclear fusion breakthrough will siphon off investments and detract attention from current renewable alternatives, just as those technologies are becoming more and more viable.

Late last year the International Energy Agency released a report with an accompanying article, headlined: “Renewable power’s growth is being turbocharged as countries seek to strengthen energy security”.

The article highlighting the report’s findings stated, “Energy security concerns caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have motivated countries to increasingly turn to renewables such as solar and wind to reduce reliance on imported fossil fuels, whose prices have spiked dramatically. Global renewable power capacity is now expected to grow by 2,400 gigawatts (GW) over the 2022-2027 period, an amount equal to the entire power capacity of China today, according to Renewables 2022, the latest edition of the IEA’s annual report on the sector.”

The international agency reported renewables are projected to provide more than 90 percent of global electricity expansion by 2027.

“Renewables were already expanding quickly, but the global energy crisis has kicked them into an extraordinary new phase of even faster growth as countries seek to capitalise on their energy security benefits. The world is set to add as much renewable power in the next 5 years as it did in the previous 20 years,” IEA Executive Director Fatih Birol, said. “Renewables’ continued acceleration is critical to help keep the door open to limiting global warming to 1.5 °C.”

Experts in Canada are echoing the success of renewables, and warning governments and the private sector that now is not the time to reduce investments.

“We know investment in fusion has grown tremendously and we can surmise that the recent announcement will help amplify those investments,” Ryan Katz-Rosene, a professor in the School of Political Studies at the University of Ottawa, says. “We also know investment in renewables continues to grow year on year we know that renewables keep getting cheaper.”

Some experts say pouring money into nuclear fusion research is not necessarily a bad thing.

“I suppose one could argue that the billions spent on fusion research and development are technically billions spent on a relatively untested energy technology which may not bring about benefits for decades, if ever,” Katz-Rosene says. “But, the counterfactual is that arguably less investment in fusion today means a longer lag time before it will be commercially viable, which means that we could miss out on years of carbon-free dispatchable energy down the road, which could in theory be exactly what we need to help us reach net zero if we overshoot our two-degree carbon budget.”

Canizares agrees. He said he is not concerned that this breakthrough will discourage investment in renewable energy because the timeframe that it will take before fusion is commercially viable, if ever, will likely be decades, not years.

According to an analysis published by Bloomberg Intelligence, there is currently $9.5 trillion in investments in renewables planned over the next 20 years. If just $1 trillion of this was taken and invested in fusion projects, nuclear fusion might be able to deliver electricity to the grid by 2030.

While the analysis by Bloomberg suggests taking money from existing renewable investments, Katz-Rosene says he is not overly worried this will detract from the broader impact of investments in renewables because it is still using the pool of available money to eliminate carbon energy. Stopping fossil fuel investments, he says, which are the biggest driver of our current emissions problem, is the key.

Katz-Rosene says the type of investor in the renewable energy sector is not the same kind of investor putting money into research and experiments into fusion.

“.125Fusion.375 is a pretty risky investment in the sense that many investors may not ever see returns. If you want to invest in low carbon energy systems that you know are possible and will likely see returns in the short term, you wouldn’t invest in fusion.”

Successful renewables and battery and storage technologies have shown they can generate a healthy return on investment.

Canizares said his position, as an academic, is to consider all viable options.

“You have to be neutral about this and think, `what is the best option on energy mixing?”’ He stresses the importance of remembering there are positives and negatives to all forms of energy generation.

Electric vehicles (EVs), for example, rely on lithium-ion batteries that contain precious minerals that require proper disposal. EVs do far less harm to the environment than vehicles with internal combustion engines that rely on gas or diesel, but as EVs become more popular, responsible battery disposal will become even more important. Canizares says these are good problems, ones that ultimately mean we are ridding the atmosphere of carbon through commitments to prevent climate chaos.

All the experts stressed that ending the use of fossil fuels is the main priority.

“To move away from fossil fuels, we need to move on to the next thing,” Bernard says. “And right now that is renewables.”

He highlights the importance of relying on technologies we can control. We have full control over solar and wind power, but not over fusion technologies. Bernard said he recognizes wind and solar cannot provide power all the time, they are intermittent, and fusion may be a solution that works alongside other proven technologies.

In 2021, the Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act was passed, committing the country to net-zero emissions by 2050. With only 27 years to reach this goal, it is unclear if fusion will be commercially viable in time to help meet the ambitious target.

“It’s unlikely that fusion is going to play a role in our transition to a carbon neutral society,” Katz-Rosene says. “We’re likely going to have to find a way to go carbon neutral without fusion.”

Despite the exciting potential of fusion and the Star Trek future it promises to shape, many experts agree—renewables have to be our priority. Continued investments and development of these alternative energies is the only viable way toward a clean electricity grid, to prevent the type of planetary harm that is irreversible.

“I think we should be looking at renewables as we are building a system that is reliable, clean and affordable,” Bernard says. “There is no magic solution.”

READ ALSO: Indigenous communities leading the switch to renewable energy in the North