Staring at the start of what he predicted might be more than 24 hours of running, Hugh Beedell felt like he was prepared.

Beedell had raced a backyard ultramarathon before in England, which he ran for just over a day before bowing out well behind the winner who he recalled finished in a mind-melting 71 hours.

That distance was out of the question for Beedell, but he still had set a goal of 50 hours or 335 kilometres of running in the forest outside Nelson. He’d brought a tent, plenty of snacks and water, and had the promise of dinner delivered by his partner. His strategy was also simple.

“Going as slow as possible, basically,” he said as he prepared for his first lap. “Slow, eating lots of food, drinking lots, keeping it easy.”

Nelson’s first backyard ultramarathon, the Tombstone Turkey Trot, began at 8 a.m. Saturday morning. To run a backyard ultra, athletes have an hour to complete a 6.7-kilometre lap. That’s typically easy for most runners, but it comes with a caveat: at the start of every hour, they have to head back out for another 6.7 km or they are disqualified.

Running that distance may start off as a relaxed jog, but as the hours pass even one lap becomes a test of endurance. The longer participants take to complete 6.7 km, the less time they have to recover before starting another lap.

Stephen Harris of the Nelson Running Club, which organized the new event, said he likes the format because it encourages a variety of athletes. Some, like Beedell, might be running for longer than a day. But most were there to set a new personal distance record in a race that felt less competitive than events that run beginning to end without a break.

“We’ve got a lot of runners here who are like, ‘Oh, the furthest I’ve ever run in my life is 10 km. So if I do two or three laps, I’ve gone further than I’ve ever gone.’ It’s a good accomplishment.”

When the race began, Lee Symmes was one of the 51 athletes to set out. He had run half marathons before and in 2013 cycled across Canada. But participating in the backyard ultra was a last-minute decision for him, and he signed up just to see how long he might last.

“I used to race mountain bikes, and you go until you finish the race then you’re done and you’d start drinking beer. And now it’s going to be hard not to start drinking beer before the race is done.”

Harris said the Tombstone Turkey Trot was inspired by the Barkley Marathons in Tennessee, an infamous race among long-distance runners that involves five loops of 20 miles (32 kilometres) in difficult terrain over 60 hours. The Barkleys began in 1986, and since then has only been completed by 17 runners.

The Nelson version was far tamer, although not without its own difficulties. The original course was set on trails above the city, but the appearance of three grizzly bears in the area forced organizers to scramble for a new course less than a day before the race was to start.

The backup route was on a flat section of trail outside the city, which would be faster for athletes but also more monotonous. Harris said he thought that might actually be worse for runners.

“Even though it’s a technically easier course to run, it’s a mentally tougher course to run when you’re 18, 20, 24, 30 hours in with no sleep.”

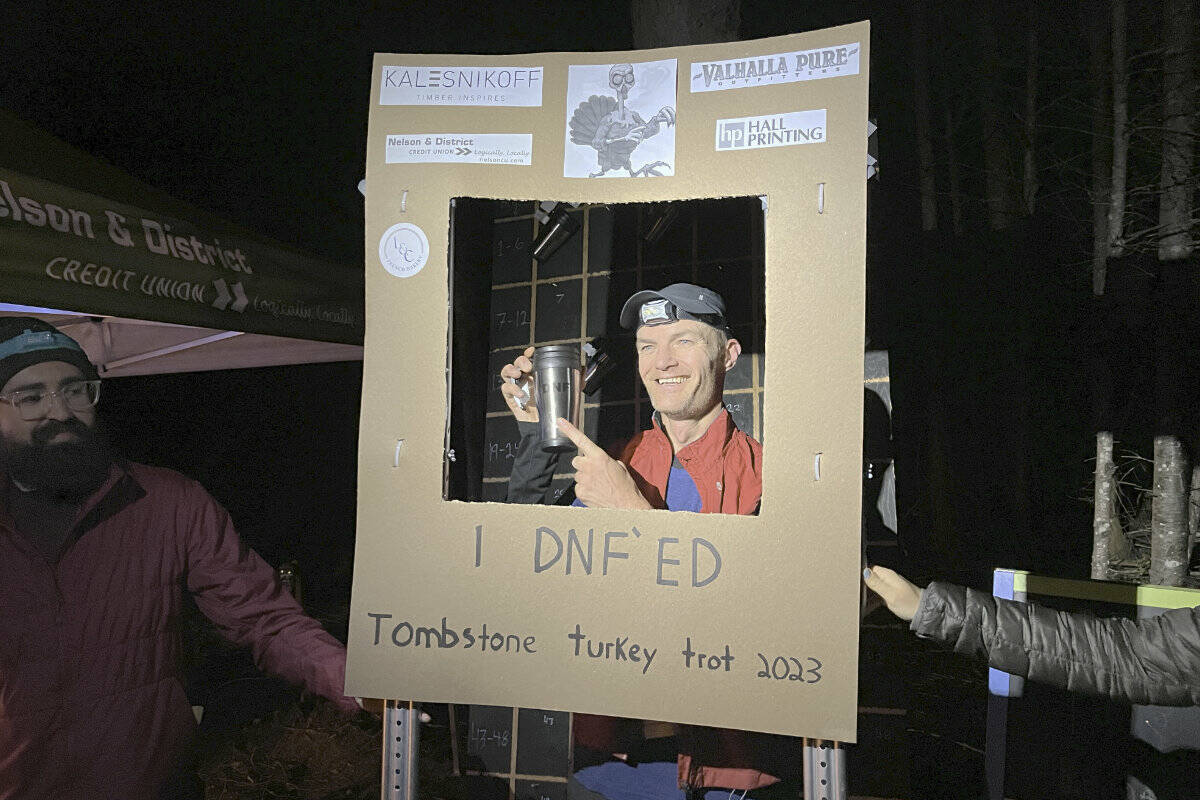

As the laps and hours ticked away, runners who had had enough posed for a picture with coffee mugs decorated with the letters “DNF” — which stands for did not finish — that the club gifted as a celebratory sign of defeat.

Of the 51 runners who started, 20 remained after nine laps or just over 53 kilometres. By the end of lap 15, or 100.5 km, at about 10:40 p.m., only five remained.

Emmanuel Malenfant was among the runners who waved the white flag at triple digits. His further run before the event was 50 km, and his goal Saturday was to reach 80. Hitting the century mark felt like an appropriate time to stop.

“I could go more but my bed is calling me. I’m happy with 100, otherwise it would have to be like 120.”

Less than a week before the race, Jaclyn Dexter had completed a local 15-km trail run to mark National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. She said her goal was to run 10 laps Saturday, and when she hit that mark she started to wonder how much further she could go.

“As you’re going you’re kinda like, ‘I can keep going all night maybe.’ When you’re feeling good your mind starts to tell you, ‘you got this, 24 [hours].’ Not necessarily.”

Instead she completed 100 km and decided she would save energy for Thankgiving the next day.

Monte Comeau also left at the same time as Malenfant and Dexter. The Salmo resident’s goal was to run his age, which for him meant 67 km. He credited his coach Jasmine Lowther, Nelson’s sports ambassador and one of Canada’s best ultramarathoners, with helping him double his previous best distance.

“You kind of get in the zone and you don’t think about much. When something starts to hurt, I tried to think about different things going on in my life.”

The race went on without them and it included Beedell, who was struggling. He had eaten too much at around laps 11 or 12, and spent the next couple hours feeling as though he might vomit. His time had also slowed, and he was only getting about five-minute breaks before the next lap would start.

But slowly the nausea disappeared, and Beedell began to find his pace again.

“It sort of worked out in my favour because then once I had my energy kicked back in everyone else is feeling a little bit low and I think that was sort of the difference. They were all like, ‘wow, Hugh’s bouncing off the walls again’ and everyone else was ready to pack it in.”

On lap 17, after midnight Sunday morning, Beedell set out with three other runners. He was feeling well, and started by walking with a donut before picking up the pace. He passed one athlete and noticed they were walking for the first time all day.

Beedell finished the lap in under 50 minutes and felt strong. He chatted with volunteers, some of whom had been onsite since 6 a.m. Saturday morning, then prepared for his 18th lap. But as he waited, he realized his competitors were lagging. One arrived with three minutes to spare, another with only seconds.

They were done, but to win Beedell technically had to complete one more lap. He did so with Harris riding along on a bike — “to make sure I didn’t get eaten by anything,” joked Beedell — and when he returned he had completed 120.6 kilometres just before 2 a.m.

He’d prepared to run more than 24 hours. Eighteen, it turned out, was more than enough.

READ MORE:

• New Nelson trail race to mark National Day for Truth and Reconciliation