Finley Comartin found out he had dyslexia at the beginning of Grade 4, but it took a long time to discover and it wasn’t cheap.

Diagnosing the 10-year-old elementary school student cost his Greater Victoria area family almost $4,000.

“Because my son was not a problem child in class, he just kept getting pushed and pushed so we eventually did it ourselves and yeah, I do not think parents should have to pay almost $4,000 just to find out,” said his mom, Deanna. “It’s absolutely unfair.”

Unlike many other learning disorders, to be diagnosed with dyslexia students have to go to an educational physiologist. For students and parents, it can cost anywhere from $3,000 to $4,000, but with ADHA most people can see a general practitioner for an inexpensive diagnosis, according to Dyslexia BC.

Since Finley was in kindergarten, his mother said he “was flagged in the school system as a student to be watched and just to see where he’s at. Basically every year he was struggling in school and every year they kind of said, ‘Oh we’ll wait and see what happens. We might maybe get him looked at or assessed in Grade 3,’ but it never happened.”

Deanna believes schools should be detecting dyslexia in kindergarten, so it can be spotted earlier.

“It’s harder to learn later in life than it is to learn when you’re younger,” she said.

Founding member of Dyslexic BC, Cathy McMillan, agrees and has written letters to the provincial government asking for early detection funding for dyslexic students.

“We need to start screening for dyslexia starting in kindergarten so that we catch our struggling readers right away. Rather than being reactive, we want to be proactive,” said McMillan. “We’ve been consistently asking for funding for starting screening in kindergarten.”

Not only does McMillan think early screening would prevent students from struggling with dyslexia, but the material being used in the classroom should also be updated.

“A second ask is funding to switch to use of structured literacy in all classrooms, both in the mainstream classrooms as well as the special education classrooms,” she said. “We’ve also been asking for funding to start training teachers so that they can start using the science of reading as well as that they can recognize dyslexia in a classroom.”

Currently in B.C., the method being used was developed in the 1960s, known as balanced literacy. This only effectively reaches about 40 per cent of students according to McMillan.

“So because we’re not using more up-to-date materials for teaching reading, it actually appears as if there are more students with reading issues like dyslexia than there actually is.”

McMillan wants the province to switch to structured literacy or the science of reading. The U.S. is currently making “legislation to ensure that they’re switching to structured literacy,” she said.

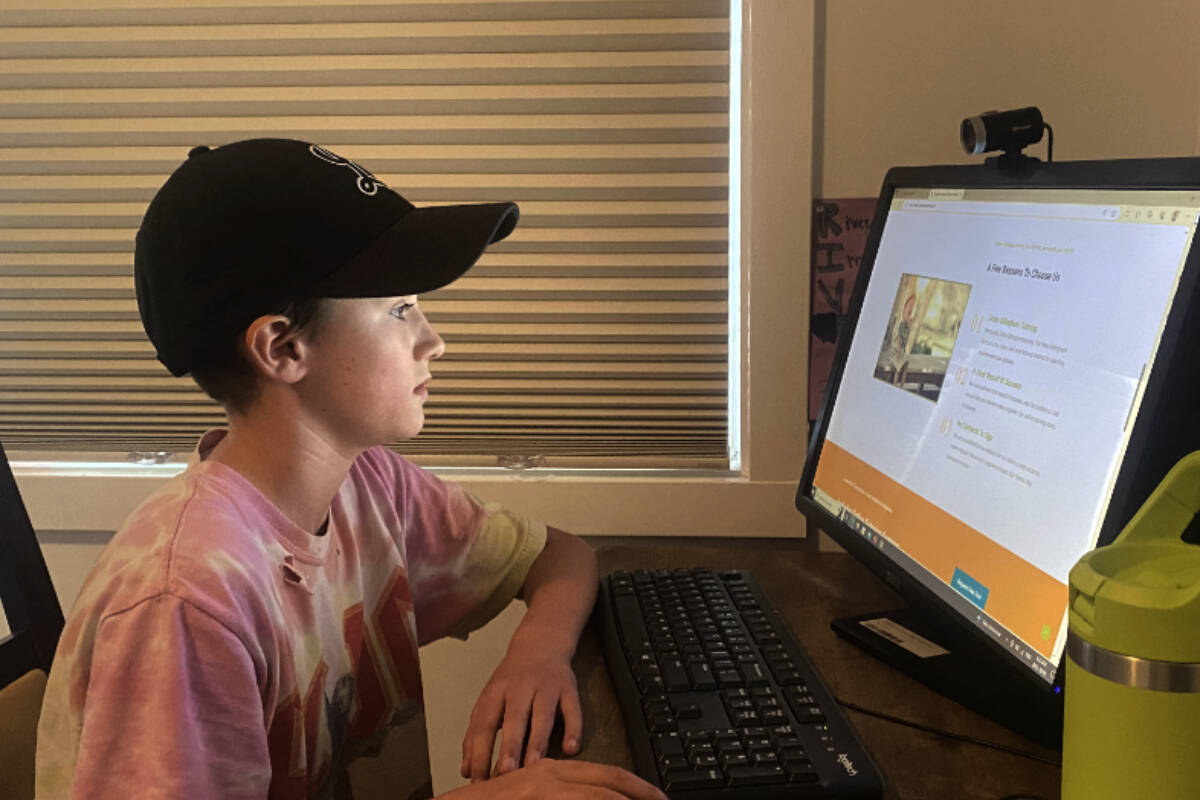

Due to the provincial school system teaching outdated material, parents like Deanna pay out of pocket for tutoring. Her son does his tutoring with an American company called Dyslexia Connect. The tutor uses the Orton Gillingham approach, which is “a direct, explicit, multi-sensory, structured, sequential, diagnostic, and prescriptive way to teach literacy when reading, writing and spelling” according to Orton-Gillingham Academy.

The Orton-Gillingham is a specialized approach for dyslexic students, but it’s expensive. Dyslexia Connect can cost up to $629 a month and even at the lowest rate it costs $229 a month, according to its website.

“There is no access to service for dyslexia in the entire province that’s equitable,” said McMillan. “We want them to get resources they need in B.C. public schools.”

Although Finley has moved up eight reading levels since having his tutor’s help, he still can find school to be hard at times. “Well, I’ve noticed that I have a hard time doing math when everyone else is like, done. Usually, I’m one of the last ones to be done doing work,” he said. “It can just be quite hard to do most things that everyone else can do.”

At times Deanna has been worried about Finley’s dyslexia as a parent.

“When we would read after school because they always say, ‘Make sure you’re reading 20 minutes a day to your child.’ He would just start crying and not want to read and it was always a bit of a struggle.”

McMillan remembers in school herself having dyslexia and how hard it was for her to write papers and get good marks. She said she remembers “being bullied as a child and even into my work world later on. If you’re trying to write papers at work, it takes you longer. There were certain times when some of my colleagues weren’t very nice.”

RELATED: ‘Courage and strength’: Bullied Victoria boy to be featured on Variety Show of Hearts Telethon

On Oct. 3 parents, students and advocates rallied outside of the legislature in Victoria, calling for more support for kids with dyslexia.

“It was super important for us to go to this event because we ended up paying out of pocket to get him assessed at the beginning of grade four, and it was the best thing we had ever done since finding out he has dyslexia. We now have the tools in place to support him,” said Deanne after attending the protest.

On Oct. 9 McMillan wrote a letter on behalf of Dyslexia B.C. to suggest measures to address the lack of support. It was sent to the BC Teachers’ Federation, BC Confederation of Parent Advisory Councils, and BC School Trustees Association. Some of the requests the organization has are that schools implement dyslexia screening starting in kindergarten, provide access to structured literacy instruction for all students, and establish specialized remedial centres in each district to cater to the needs of dyslexic students.

ALSO READ: ‘So much pain’: Donations needed for Victoria kitten’s eye-removal surgery