Indigenous Peoples have been part of Canada’s military history dating back to the War of 1812, when it’s estimated more than 10,000 First Nations people fought.

More than 7,000 Indigenous people later served in the First and Second World Wars and the Korean War. Many continue to serve today.

Wednesday is National Aboriginal Veterans Day, which was first observed in Winnipeg in 1994.

The Canadian Press spoke with three Indigenous soldiers about why they enlisted:

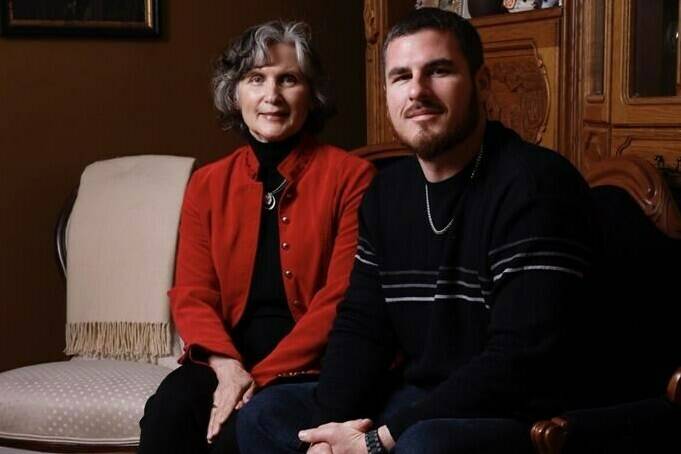

Wendy Jocko, 63, from Pikwàkanagàn First Nation in Ontario

Jocko hails from generations of Canadian soldiers. The first was Constant Pinesi, an influential grand chief of the Algonquins, who fought with the British during the War of 1812.

“It has been said that if it wasn’t for Indigenous warriors, Canada might not be Canada, because they were quite skilful in their tactics,” says Jocko.

Four of her uncles served in the First World War, but only two came home. Her father and his six brothers fought in the Second World War.

Jocko calls herself a “war baby.” While in Europe, her father met her mother, a Scottish soldier.

She says she wanted to join the military since she was four and did so when she was 19.

Being a woman at the time wasn’t advantageous, she says. “There was a bit of prejudice happening there.”

“The hardship I experienced as a child put me in a good place for life in the field, in the military.”

She was a supply technician for 23 years and served in NATO peacekeeping missions in Bosnia in 1993 and 1998. The devastation and human misery were sad to witness, she says.

Jocko rose to sergeant and retired in 2002. In 2020, she became chief of Pikwàkanagàn.

She encouraged her son, James McMullin, to join the military as well. He later left the military and died last month at the age of 38.

Jocko says she has chosen to have him laid to rest on National Aboriginal Veterans Day at Pikwanagan.

Chuck Issacs, 59, Métis from St. Albert, Alta.

Isaacs says his maternal grandfather served as an engineer during the Second World War. He didn’t speak much about the war but had a room at home full of guns.

“From five-years old, when we would visit my grandparents, we would go outside. Me and my two brothers would be given a box of ammunition and direction on what to do.”

Isaacs paternal grandfather was an armoured officer in the Second World War and also didn’t talk about his time in battle.

“As I grew up, I realized that many of the people I was surrounded by were either veterans of the Second World War or veterans of Korea.”

Issacs says he saw the financial stability military officers had, which drew him into the military.

“There were other Indigenous Peoples there with me, not that we acknowledged that or talked about it. But there were a lot more people with a like sense of humour that I had grown up with.”

It was like being introduced to a bunch of brothers and sisters, he says.

In 1992, Issacs was deployed as a combat engineer to the former Yugoslavia. He established friendships with locals and retrieved intelligence information. He also “cleared mines and ordinates and tried to make the country safe.”

Issacs left the military in 2001 and ran a promotional products company.

He now helps young Indigenous people wanting to get involved in the military and is the president of the Aboriginal Veterans Society of Alberta.

For the last four years, he’s been recruiting for the Bold Eagle program, which combines Indigenous culture and teachings with military training.

Pte. Carter Eyahpaise, 21, from Beardy’s and Okemasis’ Cree Nation, Sask.

Eyahpaise says he’s proud to be a Willow Cree soldier raised at Beardy’s and Okemasis’ Cree Nation near Prince Albert, Sask.

He recently graduated from the Bold Eagle program in Alberta and loved it so much that he decided to join the North Saskatchewan Regiment of the Forces near his home reserve.

Eyahpaise says he was inspired by his great-grandfather Stanley Eyahpaise of the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada in Winnipeg. He was killed in France during the Second World War.

“I wanted to be great like he was. He was part of Juno Beach in the second wave,” says the younger Eyahpaise.

Wearing a uniform was a big dream growing up, he adds.

“And I was always into video games like “Call of Duty,” “Medal of Honor,” and all of that stuff.”

Eyahpaise says his family is proud of him for enlisting, but it worries his mother.

He says he wants to work his way up the ranks to become a captain someday.

“I really wanted to be a part of something.”

READ ALSO: Victoria man follows seven generations of Indigenous veterans

READ ALSO: Organization continues search to identify Indigenous veterans in unmarked graves