Two scientists won the Nobel Prize in medicine on Monday for discoveries that enabled the creation of mRNA vaccines against COVID-19 that were critical in slowing the pandemic — technology that’s also being studied to fight cancer and other diseases.

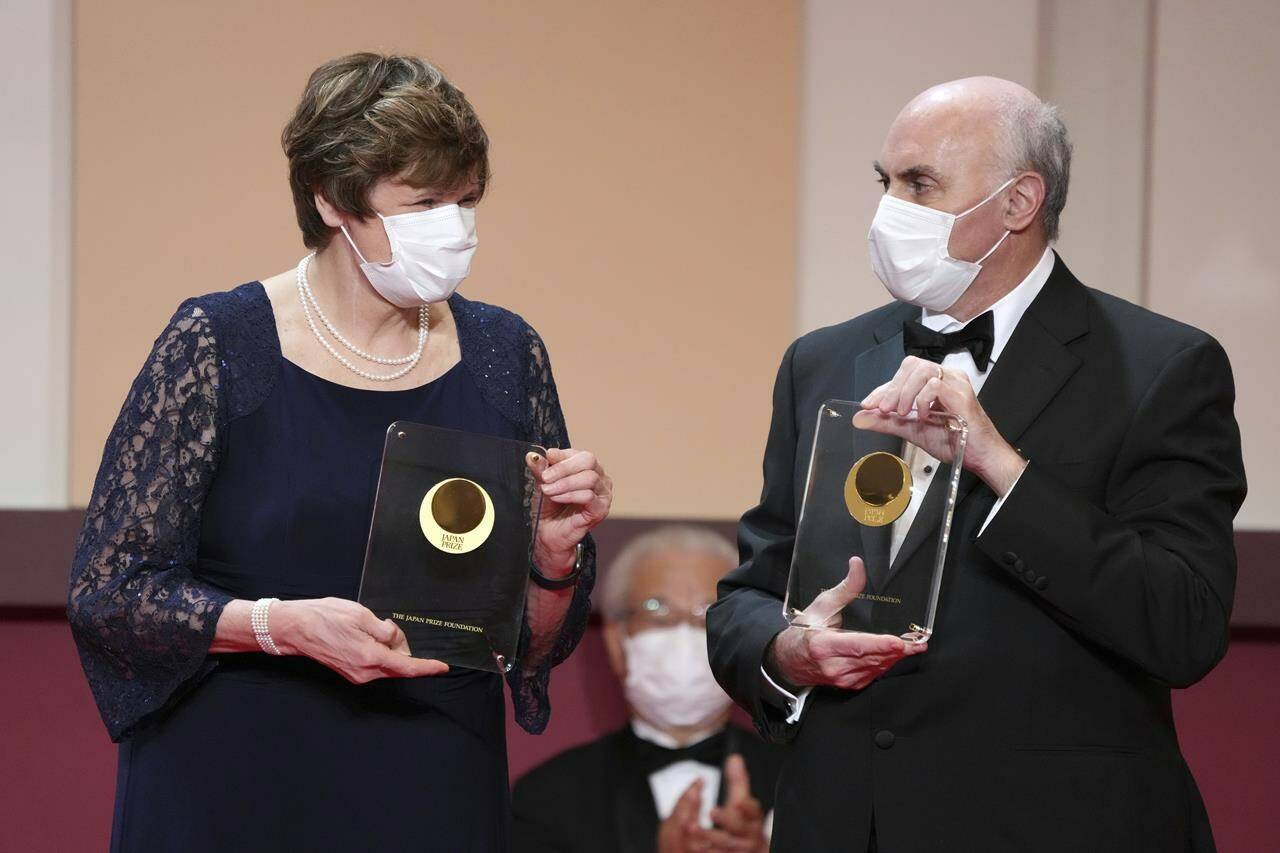

Hungarian-American Katalin Karikó and American Drew Weissman were cited for contributing “to the unprecedented rate of vaccine development during one of the greatest threats to human health,” according to the panel that awarded the prize in Stockholm.

The panel said the pair’s “groundbreaking findings … fundamentally changed our understanding of how mRNA interacts with our immune system.”

WHAT IS THE NOBEL PRIZE FOR?

Traditionally, making vaccines required growing viruses or pieces of viruses and then purifying them before next steps. The messenger RNA approach starts with a snippet of genetic code carrying instructions for making proteins. Pick the right virus protein to target, and the body turns into a mini vaccine factory.

In early experiments with animals, simply injecting lab-grown mRNA triggered a reaction that usually destroyed it. Those early challenges caused many to lose faith in the approach: “Pretty much everybody gave up on it,” Weissman said.

But Karikó, a professor at Szeged University in Hungary and an adjunct professor at the University of Pennsylvania, and Weissman, of the University of Pennsylvania, figured out a tiny modification to the building blocks of RNA that made it stealthy enough to slip past immune defenses.

Karikó, 68, is the 13th woman to win the Nobel Prize in medicine. She was a senior vice president at BioNTech, which partnered with Pfizer to make one of the COVID-19 vaccines. Karikó and Weissman, 64, met by chance in the 1990s while photocopying research papers, Karikó told The Associated Press.

WHY DO MRNA VACCINES MATTER?

Dr. Paul Hunter, a professor of medicine at Britain’s University of East Anglia, described the mRNA vaccines made by BioNTech-Pfizer and Moderna Inc. as a “game changer” in shutting down the coronavirus pandemic, crediting the shots with saving millions of lives.

“We would likely only now be coming out of the depths of COVID without the mRNA vaccines,” Hunter said.

John Tregoning, of Imperial College London, called Karikó “one of the most inspirational scientists I have met.” Her work together with Weissman “shows the importance of basic, fundamental research in the path to solutions to the most pressing societal needs,” he said.

The duo’s pivotal mRNA research was combined with two other earlier scientific discoveries to create the COVID-19 vaccines. Researchers in Canada had developed a fatty coating to help mRNA get inside cells to do its work. And studies with prior vaccines at the U.S. National Institutes of Health showed how to stabilize the coronavirus spike protein that the new mRNA shots needed to deliver.

Dr. Bharat Pankhania, an infectious diseases expert at Exeter University, predicted the technology used in the vaccines could be used to refine vaccines for other diseases like Ebola, malaria and dengue, and might also be used to create shots that immunize people against certain types of cancer or auto-immune diseases including lupus.

HOW DID KATALIN KARIKÓ AND DREW WEISSMAN REACT?

“The future is just so incredible,” Weissman said. “We’ve been thinking for years about everything that we could do with RNA, and now it’s here.”

Karikó said her husband was the first to pick up the early morning call, handing it to her to hear the news. And Karikó was the one to break the news to Weissman, since she got in touch before the Nobel committee could reach him.

Both scientists thought it was a prank at first, until they watched the official announcement.

“I was very much surprised,” Karikó said. “But I am very happy.”

The two have collaborated for decades, with Karikó focusing on the RNA side and Weissman handling the immunology: “We educated each other,” she said.

Before COVID-19, mRNA vaccines were already being tested for diseases like Zika, influenza and rabies — but the pandemic brought more attention to this approach, Karikó said. Now, scientists are trying out mRNA approaches for cancer, allergies and other gene therapies, Weissman said.

“It’s already been going on for many years, but this has just given RNA the recognition,” Weissman said.

Karikó’s family is no stranger to high honors. Her daughter, Susan Francia, is a double Olympic gold medalist in rowing, competing for the United States.

The prize carries a cash award of 11 million Swedish kronor ($1 million) from a bequest left by the prize’s creator, Swedish inventor Alfred Nobel. The laureates are invited to receive their awards at ceremonies on Dec. 10, the anniversary of Nobel’s death.

Nobel announcements continue with the physics prize on Tuesday, chemistry on Wednesday and literature on Thursday. The Nobel Peace Prize will be announced Friday and the economics award on Oct. 9.

___

This story has been updated to correct that Karikó is a professor at Szeged University, not Sagan’s University.

___

Corder reported from The Hague, Netherlands. Burakoff reported from New York. Associated Press writers Maria Cheng in London and Lauran Neergaard in Washington contributed.

___

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

___

Follow all AP stories about the Nobel Prizes at https://apnews.com/hub/nobel-prizes

David Keyton, Mike Corder And Maddie Burakoff, The Associated Press