One of the first to take the microphone, Mary Vickars faced a crowd of several hundred as she spoke about the stick her mother often had waiting for her after school.

The “swarms of hits” were frequent, but one day it got worse.

With a determined but quivering voice, Vickars told of the morning her mother lunged at her, out of the blue, with a machete.

“I saw myself with my six brothers running down the street to save my life,” she said. “I couldn’t comprehend how a mother could do that to her only daughter.”

Vickars is an intergenerational survivor of residential schools, the daughter of a woman who attended St. Michael’s school in Alert Bay near the northern tip of Vancouver Island, between the ages of three and 16.

On Friday at the Victoria Conference Centre, she joined dozens of others from across Vancouver Island who volunteered to speak about their experiences of residential school at the national Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s event in Victoria, April 13 and 14. They spoke for the record, for personal healing and for cross-cultural understanding.

“Seeing all the drinking and the infidelity of our people was outrageous,” Vickars said, her face projected onto a large screen for all to see clearly in the darkened conference room. “It was dysfunctional, but to us it felt so normal, because the whole community was doing it.”

The goal of the commission is to create a national memory around residential schools for future generations, chair Murray Sinclair told more than 1,000 people gathered at the opening ceremonies Friday at Crystal Garden.

“We never want it to be said in this country at any time in the future that this never happened.”

The event also aimed to set the groundwork for reconciliation, he added.

The relationship between Aboriginal Peoples and non-aboriginals has been damaged, he said. “The tension that goes on in this society is significant … and the relationship will have to be addressed for future generations, so that future Canadians will be able to mutually exist without that tension.”

Over two days, the commission gathered statements from survivors and their families. From these, common themes emerged of harsh punishments at school, languages lost, broken families and intergenerational neglect and abuse. Memories of specific incidents, however, brought home these large-scale traumas.

One woman told of hearing the screams of children on the day a dentist came to her school and pulled out teeth without freezing.

One man told of secretly caring for a puppy, feeding him bread stolen from the kitchen. When he was caught, a priest instructed him to drown the dog in a gunny sack. “He said don’t take your eyes off it until the bubbles stop.”

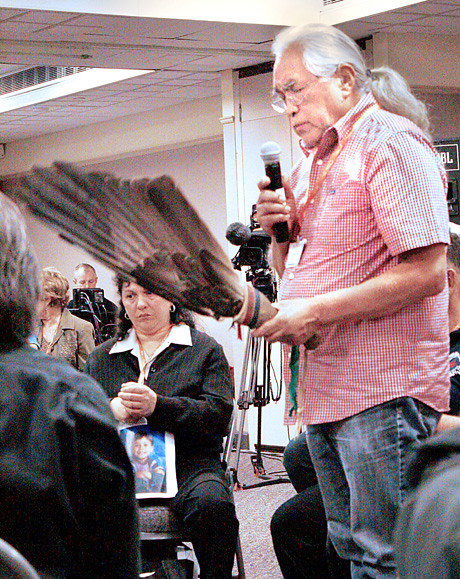

William Jones chose to speak in the more intimate setting of a sharing circle.

Holding the eagle feather, he sat with other survivors while witnesses listened from outside the circle and mental health supporters, dressed in white, stood by with tissues.

“I beat my wife like any other drunken Indian,” said Jones (left).

It’s taken all these years to understand the source of his problems.

“I likely would have succeeded had I not been destructuralized.”

When the man who molested him and other boys at Alberni residential school was tried in court, Jones didn’t have the courage to participate.

“I could never admit to myself what that man had done to me,” he said.

After 30 years of sobriety and 20 years of work with psychiatrists and psychologists, that changed. “It was time for me to say something and maybe put it in someone else’s lap,” he said.

Many other people shared stories of healing and success, despite a childhood of abuse.

A Pacheedaht man spoke proudly of being the owner of a restaurant.

Perry Omeasoo spoke of rising to the position of president of the Vancouver Native Health Society. “I like the person I’ve become,” he said.

Vickars found a way to forgive her stick-wielding mother.

“I couldn’t comprehend being three years old, with your siblings, and being taken away,” Vickars said, sobbing. “What I went through was (nothing in comparison).”

Her experience influenced how she parented her own kids.

“There are numerous of us, in my generation, that never got a childhood and when my children came I made sure that they had everything.”

More than truth telling, the Truth and Reconciliation event served as a call to action.

“We need to figure out how we move forward,” said commissioner Marie Wilson, addressing both the survivors and all the people of Canada. “We are all part of that obligation.”

She called on everyone in the audience to be witnesses at the event and to continue the conversation into the future.

“We need helpers… who will help us turn the word ‘witness’ into an active verb,” said Wilson. “We are actually asking you to join a movement.”

rholmen@vicnews.com

Links to previous stories in series:

• Songhees people will host, but few expected to speak

• OPINION: What we didn’t learn in school

• Victoria artist explores shared pain of residential schools through art

• Residential school survivors tell their truths in Victoria