A column by Bruce Uzelman

The Fraser River Gold Rush began in 1858. Miners descended on the river’s sand bars, tributaries and creeks. Before the construction of the Cariboo Wagon Road in the early 1860s, accessing the Fraser River and Cariboo gold fields was arduous, as was exiting the region.

Early miners had to endure the Douglas Road, built in 1858 and rebuilt in 1859. The road began in Port Douglas at the head of Harrison Lake. The journey north over nine alternating land and steamer legs was expensive and prolonged. The miners were a diverse lot – Canadians, Americans, Europeans, Chinese and Indigenous – all moving relentlessly toward the goldfields.

The terminus of the Douglas Road would soon become Mile 0 of the Old Cariboo Road as well, a uniquely favourable location for a town. Here, the gold rush town of Lillooet sprang up. Sixteen thousand miners were outfitted in the town, before they dispersed to the Fraser and its tributaries and creeks, or across the Cariboo as the gold rush took hold there.

Lillooet was sited within the territory of the Northern St’at’imc, a progressive people who had thrived here for thousands of years. B.C. historian, Bill Barlee, said the fisheries here were amongst the best on the Fraser. The St’at’imc built sizable villages, and lived in large pit houses with elaborate timber roofs. Archeologists excavated one which was 13 meters in diameter.

Lillooet soon became a multi-ethnic, boom town, said to be the largest town west of Chicago and east of San Francisco. The Lillooet Chamber of Commerce states the population reached 15,000. That is doubtful, but the town was bursting. (It perhaps had 2000-5000 permanent residents.)

On the Fraser River, paddle-wheelers travelled only as far north as the town of Yale, just above Hope. Beyond Yale, the river was unnavigable. Miners were apparently forced to travel on foot over river trails. Some miners did chance their return south on the swift and fierce Fraser.

Rafting the Fraser below Lillooet posed a clear risk of death; riding the Fraser above Lillooet and the confluence with the Bridge River posed a certainty of death. Below Lillooet, the river was swift and turbulent, particularly through the aptly named Hell’s Gate. But above the mouth of the Bridge, “the water hisses,” said Barlee. If you fell in, “you could not, could not extricate yourself….”

Barlee maintained that 200 lives were lost along the river south to Yale. Miners, tossed from their rafts and weighted down by their gold pokes (pouches), were unable to escape the rushing waters.

The Douglas Road did not offer an affordable and practicable route north, and the Fraser route, with minimal transportation infrastructure, certainly was unacceptably treacherous. So, the Governor of British Columbia, James Douglas, authorized the construction of the Caribou Wagon Road through the Fraser Canyon in 1861. Lillooet prospered from 1859-1861, and continued to prosper in 1862.

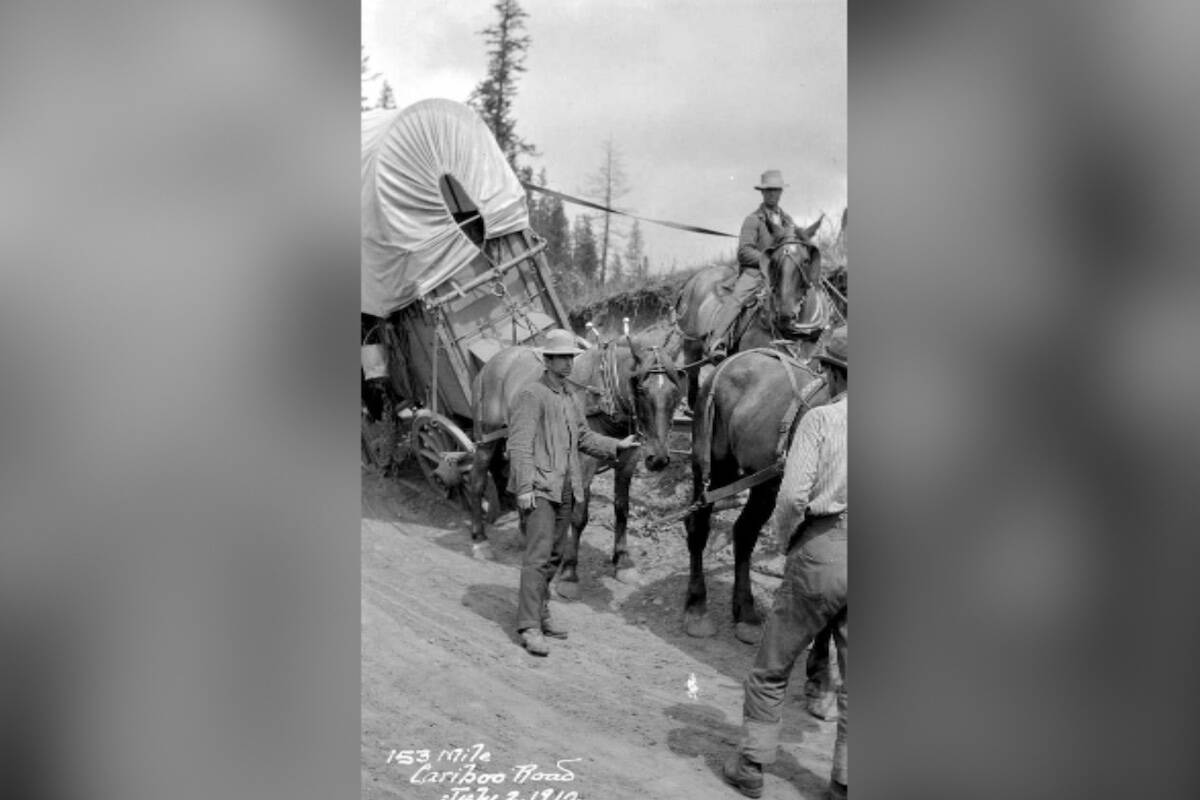

The new road was completed to Lytton in 1863, to Fort Alexandria soon after and to Barkerville in 1865. The road accommodated stagecoaches, freight wagons and horse traffic. Now, the Cariboo goldfields could be accessed in relative comfort and safety.

Lillooet’s location, however, was no longer advantageous. The Cariboo Wagon Road bypassed the town. The boom in Lillooet was extinguished, but it retained many of its residents and its diversity. Many Chinese residents stayed on as merchants, miners and ranchers, and remained part of the community for decades. Many white and Indigenous residents stayed on as well.

The Bridge River Country is just north of Lillooet. Placer mining began on the Bridge River and its creeks in 1858 or 1859, with good results. But the big strike here did not happen until the 1890s, when prospectors turned their attention to Cadwallader Creek. A number of miners staked claims in the area in 1896 and 1897, and developed several successful hard-rock mines above the creek.

Amongst them were the Lorne and the Pioneer. The Lorne was purchased by Bralco Development and became the Bralorne in 1931. It employed as many as 400 miners. Each mine boasted a self-contained company town, which had their own schools, theatre, recreation center and hospital.

“The Bralorne complex [consisting of The Bralorne, Pioneer and King Mines] was the highest-grade gold producer in Canada before it closed in 1971,” according to the Canadian Mining Journal. In addition, the complex produced more than 4.2 million ounces of gold and 1 million ounces of silver.

The complex is now owned by Talisker Resources, which intends to begin test mining in the second quarter of 2024. The mining journal says the company, “is aiming to clear a pathway to a resource containing 5.0 million oz. of gold or more.” At least for company investors, the gold rush is back!

The two historic communities, Lillooet and the Bridge River Country, no doubt, have a great future.

Bruce Uzelman, based in Kelowna, holds interests in British Columbia history as wells as current political and economic issues.

Bruce had a career in small business, primarily restaurant and retail. He holds a Bachelor of Arts, Advanced from the University of Saskatchewan, with Majors in Political Science and Economics.

Contact: urban.general@outlook.com